The Plots Thicken - Defence Against Aerial Attack (Feb 23)

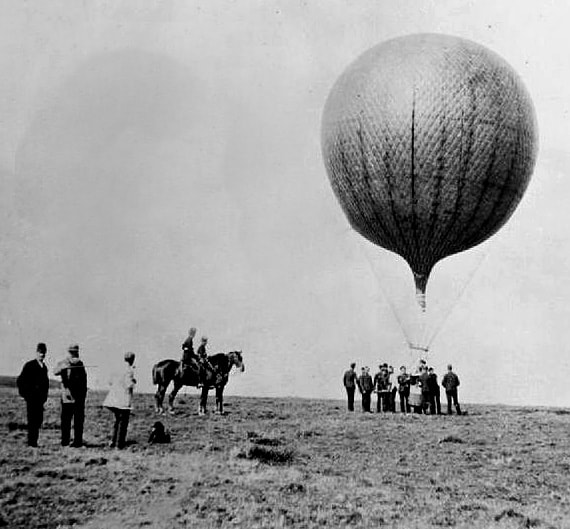

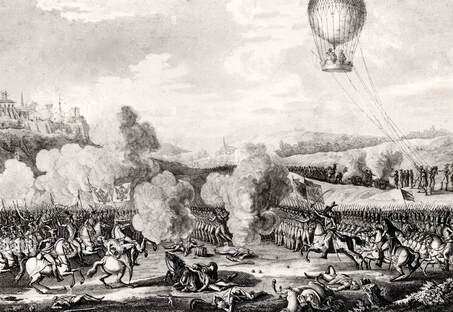

After man first took to the air in 1783 the military mind soon focused on how to use the elevated position for observation and reconnaissance. Ballooning was only ten years old when the French formed the Corps d'Aerostiers to fly - usually tethered - balloons to see what the enemy was doing in the French Revolutionary Wars.

The Battle of Fleurs - 1794

Balloons weren’t really suitable to be offensive but dropping bombs from free balloons was tried (the Austrian siege of Venice in 1849) and determined to be too haphazard. Also it usually incurred the loss of the balloon and its occupant.

The Battle of Fleurs - 1794

Balloons weren’t really suitable to be offensive but dropping bombs from free balloons was tried (the Austrian siege of Venice in 1849) and determined to be too haphazard. Also it usually incurred the loss of the balloon and its occupant.

Their offensive days were not exactly over after 1849. The Japanese used the newly discovered jet stream to send over 300 balloons across the Pacific carrying explosives and incendiaries. Most fell in the sea or landed unnoticed in open country but they did cause many small fires and six deaths, though no-one noticed because there was a press blackout - to avoid causing panic.

And no-one in the UK noticed that the Royal Navy used 100,000, yes, 100,000 weather balloons in Operation Outward. (Why did they have so many in store?)

And no-one in the UK noticed that the Royal Navy used 100,000, yes, 100,000 weather balloons in Operation Outward. (Why did they have so many in store?)

Starting in August 1942, balloons were released in clusters {flocks, fleets?) carefully timed to avoid any Bomber Command streams over the North Sea. On days when the wind was not at its best an all-day trickle of single balloons was released. Reports, usually in German local newspapers, soon showed they were being very effective, causing many fires and power outages - one caused the complete destruction of a power station. And even if there was little damage, the enemy was wasting much time and fuel using fighters to shoot down the irritating invaders. They didn’t all behave properly. Some reached as far as Poland, some came down in Norway and in northern England and there was a brief outburst of diplomacy after the Swedish tramcar incident. The Navy went back to its normal duties after they launched the last of their balloons in September 1944.

(Note that Operation Outward preceded the Japanese balloons, the first of which didn’t land in the US until November 1944. Was Outward their inspiration?).

Back in 1914 when aeroplanes appeared on the battle front they supplemented the work of the observation balloons. However, they were not tied to their launching point and roamed over their own and enemy territory. They were a threat to at least half the people below them and deserved to be shot at. The troops had to be deterred from shooting at their own aeroplanes so markings were introduced. The RFC first tried Union Jacks - took ages to paint and too many lines and colours to be an easily recognised symbol. The French roundel was better and a simple reversal of colours distinguished British from French. It was not enough to prevent ‘friendly fire’ causing the destruction of too many aeroplanes - on both sides of the trenches. Anti-aircraft gunners, whose targets were too far away for any markings to be seen, learned to identify aeroplanes by their shape. They were the first to become skilled at aircraft recognition. The Army realised that this was something that all fighting men should be taught and set up a school of aircraft recognition (the navy declined to take part.)

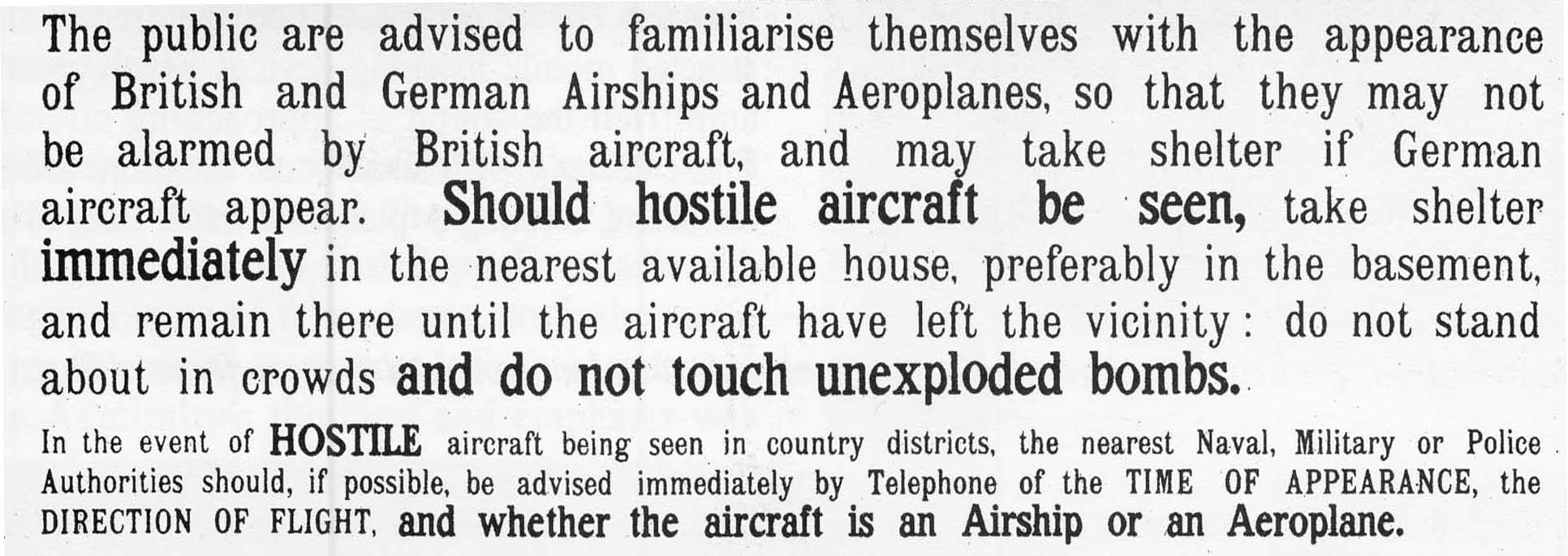

It was needed not only by the men at the front but also at home in England although identification of the enemy in the air was not really a problem. Only the Germans had a fleet of Zeppelins and they were the things widely expected to appear in the sky to rain down bombs on the defenceless civilian population.

For centuries it had been the Navy’s responsibility to guard our shores so, spurred on by the First Lord of the Admiralty, one Winston S Churchill, a committee was formed to establish the defences. A line of seaplane stations around the coasts of SE England and East Anglia was boosted by airfields manned by RNAS aeroplanes. The Army provided the coastal AA gun stations and searchlights. London itself was surrounded by another ring of guns and searchlights, manned by an Anti-Aircraft Corps - largely men from the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve. They were supplemented by civilian volunteer observers (unemployed, retired or working in the time off from their normal day jobs, who were signed up as Special Constables. They were posted to places with a good view of the sky and easy access to a public telephone. They reported their sightings to the nearest defence unit, usually a gun battery or an airfield.

Back in 1914 when aeroplanes appeared on the battle front they supplemented the work of the observation balloons. However, they were not tied to their launching point and roamed over their own and enemy territory. They were a threat to at least half the people below them and deserved to be shot at. The troops had to be deterred from shooting at their own aeroplanes so markings were introduced. The RFC first tried Union Jacks - took ages to paint and too many lines and colours to be an easily recognised symbol. The French roundel was better and a simple reversal of colours distinguished British from French. It was not enough to prevent ‘friendly fire’ causing the destruction of too many aeroplanes - on both sides of the trenches. Anti-aircraft gunners, whose targets were too far away for any markings to be seen, learned to identify aeroplanes by their shape. They were the first to become skilled at aircraft recognition. The Army realised that this was something that all fighting men should be taught and set up a school of aircraft recognition (the navy declined to take part.)

It was needed not only by the men at the front but also at home in England although identification of the enemy in the air was not really a problem. Only the Germans had a fleet of Zeppelins and they were the things widely expected to appear in the sky to rain down bombs on the defenceless civilian population.

For centuries it had been the Navy’s responsibility to guard our shores so, spurred on by the First Lord of the Admiralty, one Winston S Churchill, a committee was formed to establish the defences. A line of seaplane stations around the coasts of SE England and East Anglia was boosted by airfields manned by RNAS aeroplanes. The Army provided the coastal AA gun stations and searchlights. London itself was surrounded by another ring of guns and searchlights, manned by an Anti-Aircraft Corps - largely men from the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve. They were supplemented by civilian volunteer observers (unemployed, retired or working in the time off from their normal day jobs, who were signed up as Special Constables. They were posted to places with a good view of the sky and easy access to a public telephone. They reported their sightings to the nearest defence unit, usually a gun battery or an airfield.

Ironically, although the airship was the main threat, the first bombing attack - on 21 December, 1914 - was from a German Navy Taube whose bombs fell in the sea off Dover harbour. Then the first bomb to land on British soil - on Christmas Eve - was from another Taube. It fell in the garden of a house near Dover Castle. The Zeppelins didn’t arrive until 19th January 1915 when bombs fell on Yarmouth and King’s Lynn. The first attack on London was on 31st May 1915.

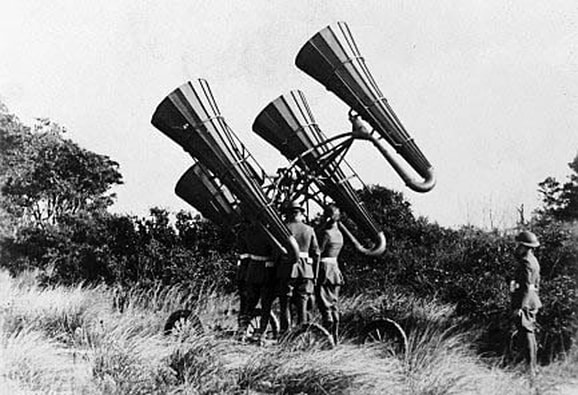

That was at night, of course and the observers saw nothing. Early detection of air attack - during the day as well as in the darkness was by sound. The first Zeppelin raiders were plotted by sound as they wandered around East Anglia looking for London. Soon focused sound detectors were produced, by all nations, and initially were positioned by anti-aircraft batteries. They all worked - when they weren’t swamped by other extraneous noises - and ranged in size from the colossal to the comic.

That was at night, of course and the observers saw nothing. Early detection of air attack - during the day as well as in the darkness was by sound. The first Zeppelin raiders were plotted by sound as they wandered around East Anglia looking for London. Soon focused sound detectors were produced, by all nations, and initially were positioned by anti-aircraft batteries. They all worked - when they weren’t swamped by other extraneous noises - and ranged in size from the colossal to the comic.

They were active and in use up to and, in some areas, even during WWII. A few are still around, notably the huge concrete ’sound mirrors’ at Hythe in Kent.

The defensive organisation was broken up and disbanded in the demilitarised and slumbering early twenties - until 1925 when the Air Defence of Great Britain was set up. Initially a committee, they drew up plans of what was needed to combat an air assault. The likely enemy was deemed to be France, not necessarily the French Air Force, just that France was the most likely launching point of the attack. Areas of concentration of guns around potential targets were designated, lines of balloon barrages plotted, airfields for defensive fighters allocated - and the Observer Corps reformed. From time to time exercises were carried out. Here are the special constables of the Welwyn Garden Observer Corps post exercising in 1933.

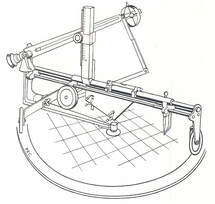

Their instrument looks distinctly home made. Something better was needed.

And here it is. The estimated height of the aircraft was set on the vertical bar. The sight was rotated and its angle adjusted by rolling it along the horizontal bar. The pointers would then give the aircraft’s position on the grid. Note the spirit level on the horizontal bar which ensured that the table was absolutely level.

The first models had the relevant Ordnance Survey map on the table instrument’s table but aircraft were not plotted by their relation to towns or ground features. The observers used the grid of 1 km. squares which are printed on OS maps. So the clutter of ground features was eliminated and plots were reported as a simple 4 number grid reference.

The first models had the relevant Ordnance Survey map on the table instrument’s table but aircraft were not plotted by their relation to towns or ground features. The observers used the grid of 1 km. squares which are printed on OS maps. So the clutter of ground features was eliminated and plots were reported as a simple 4 number grid reference.

The exercises demonstrated the effectiveness of the Observer Corps’ spotting and plotting and it was decided to expand the Corps to cover the whole country. The Post Office were pressurised to provide a large number of dedicated telephone lines between the posts and the operation centres.

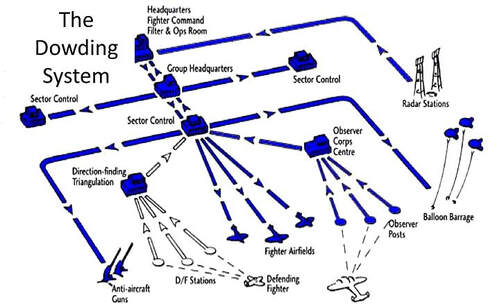

In 1936, the structure of the RAF was re-organised and Fighter Command was created. Its AOC, Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding was charged with developing and installing a comprehensive air defence system using the resources of all three services. He took over the work already done by the now disbanded ADGB and was able to take advantage of the newly developed radio direction finding and ranging - radar.

In 1936, the structure of the RAF was re-organised and Fighter Command was created. Its AOC, Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding was charged with developing and installing a comprehensive air defence system using the resources of all three services. He took over the work already done by the now disbanded ADGB and was able to take advantage of the newly developed radio direction finding and ranging - radar.

The towering aerials of the Chain Home stations appeared covering the whole east and south coasts from northern Scotland to Land’s End. The detection of any aircraft would be reported to Fighter Command’s Operations Room. In the light of what we see now of modern radar systems it’s difficult to appreciate how very basic and crude the CH radars were. They projected a signal which fanned out over the sea. Any reflection which returned from an aircraft appeared as a smear on a small screen.

The operator could tell only how far away it was. There was no indication of direction. The ‘plot’ was passed by telephone to the Ops room. The table there had a series of concentric semi-circles indicating distances from every CH station. A nearby station would have reported the raid and its distance. Where the two semi-circles intercepted was where the raid should be. But confusion could reign. If the raid were, say, 80 bombers flying in a stream on a course directly towards the first CH station the signal would be reflected from the first six aircraft. The second station would be ‘seeing’ the raid from a different angle - the reflections from 15 aircraft. Was it one raid, or two?

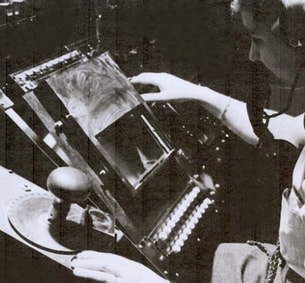

The CH returns had to be analysed and checked before deciding what was really there. So the main Ops Room was primarily a Filter Room, the workplace of specially picked - and mostly WAAF - officers, selected for their intelligence and ability to work under pressure.

The CH returns had to be analysed and checked before deciding what was really there. So the main Ops Room was primarily a Filter Room, the workplace of specially picked - and mostly WAAF - officers, selected for their intelligence and ability to work under pressure.

The Battle of Britain was a severe test for the system. As time went on the operators and Filterers became skilled at interpreting their fuzzy signals and able to assess number of aircraft in a formation and accurately plot the course changes.

Overland radar was swamped by ground returns so all plotting there was done by the Observer Corps. They plotted everything, but the Sector Control which directed the fighters had no interest in trainers and transport aircraft. They were filtered out and did not appear on the Controller’s table. On this diagram is a unit for Direction Finding Triangulation. This arose after it was noticed that sometimes a pilot’s transmission on his R/T distorted the radar return signal.

As a result, fighters were fitted with a special radio, known as pip-squeak, later IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) which transmitted a signal on a designated frequency for 14 seconds. This was received by a D/F station which gave the pilot the course to steer to reach his home base. It was the first transponder, a device nowadays fitted to most commercial aeroplanes and which ‘squawks’ showing up on radar screens and identifying the aeroplane. (The Shuttleworth Spitfire has an early version of this set. The aerials stretched from the tailplane to a point on the fuselage near the roundel. Later versions had a small whip aerial under the fuselage).

In the early days of the Battle the Germans were aware that they were being detected by some form of radar and soon worked out that the radar seemed to be blind at low level. The bombers dropping mines were never intercepted. Robert Watson-Watt, leader of the team of scientists who had developed the first radar was well aware of this low level gap and called on the Army for help. Independently, they had been working on a radar for coastal artillery to detect ships. It worked right down to sea level - occasionally, they got a better return from the splash of the shell than from the target they were aiming at. Watson Watt would be using it for low-flying aircraft - up to 3,000 ft. He ordered 12 sets. They were quite compact and fitted easily into a small hut. They were located alongside CH Station and called CHL - Chain Home Low.

In the early days of the Battle the Germans were aware that they were being detected by some form of radar and soon worked out that the radar seemed to be blind at low level. The bombers dropping mines were never intercepted. Robert Watson-Watt, leader of the team of scientists who had developed the first radar was well aware of this low level gap and called on the Army for help. Independently, they had been working on a radar for coastal artillery to detect ships. It worked right down to sea level - occasionally, they got a better return from the splash of the shell than from the target they were aiming at. Watson Watt would be using it for low-flying aircraft - up to 3,000 ft. He ordered 12 sets. They were quite compact and fitted easily into a small hut. They were located alongside CH Station and called CHL - Chain Home Low.

The set sent out a single directional beam, so the aerial was made to rotate, though not in a full circle. When a return was detected a second bearing would be taken by the next CHL station to produce a cross plot. The CHL sets produced accurate plots despite being somewhat primitive. (The aerials were rotated by pedal power, Waafs on wheel-less bicycles modified to pull the aerial to and fro).

Once the enemy had crossed the coast the controllers relied on the plots from the Observer Corps. Posts were no more than 8-10 miles apart and manned by at least two people, one with binoculars to identify the aircraft and the second to plot the sighting. Officially, the RAF wanted to know only whether the aeroplane was Friendly or Hostile. There was a third category - X - unidentified, possibly hostile.

When a plot was reported, on a permanently open telephone line, it was given an Identity by a numbered metal strip which was placed alongside the plot on the table in the Operations Room. So a Spitfire could become F 178, with magnetic numbers on the strip showing 1 at 6 (thousand feet). (The ‘Spit’ is not necessary but it could help if two Friendlies of different types are on the table).

When a plot was reported, on a permanently open telephone line, it was given an Identity by a numbered metal strip which was placed alongside the plot on the table in the Operations Room. So a Spitfire could become F 178, with magnetic numbers on the strip showing 1 at 6 (thousand feet). (The ‘Spit’ is not necessary but it could help if two Friendlies of different types are on the table).

The little arrow showing F178’s position would be coloured. The plotter would check the clock and in this case use a yellow arrow. This gives the plot a time. As soon as the plot appeared on the table a teller, sitting upstairs with a clear view of the whole table, would read off the plot to the RAF Ops room - ‘Friendly 178, 4167(the grid reference) 1 at 6’. The rule book said this had to be done within 40 seconds but it was never as long as this. If the teller was dealing with more than three plots, a second teller would take the overflow.

Posts were grouped in clusters, three or four together, all on the same telephone line to the plotter. This facilitated the passing of plots from one post to another and also allow the use of the Micklethwait.

All the post observers were experts at aircraft recognition but not good at estimating the aircraft’s height. No one is good at estimating an aircraft’s height. But it had to be done before the aircraft is sighted by the instrument and if the height is wrong, the plot is wrong - not by much, but wrong. This irritated Eric Micklethwait who joined the Observer Corps in 1940. He puzzled over the angles and worked out a solution and proudly patented it. Like all really clever devices, it’s easy to use.

The drawing of the post instrument (a couple of pages back) shows two pointers over the plot - one straight, one angled. When two posts are plotting the same aeroplane and the plots are different one post moves the angled pointer to the other post’s plot and a little scale on the other side of the instrument shows the aeroplane’s true height. Brilliant.

All the post observers were experts at aircraft recognition but not good at estimating the aircraft’s height. No one is good at estimating an aircraft’s height. But it had to be done before the aircraft is sighted by the instrument and if the height is wrong, the plot is wrong - not by much, but wrong. This irritated Eric Micklethwait who joined the Observer Corps in 1940. He puzzled over the angles and worked out a solution and proudly patented it. Like all really clever devices, it’s easy to use.

The drawing of the post instrument (a couple of pages back) shows two pointers over the plot - one straight, one angled. When two posts are plotting the same aeroplane and the plots are different one post moves the angled pointer to the other post’s plot and a little scale on the other side of the instrument shows the aeroplane’s true height. Brilliant.

Plotting went on at night. The aeroplanes couldn’t be seen but they could be heard and a post would report just that ‘Heard 35’. 35 is the direction of the sound - 35 minutes on a clock face. The numbers were marked around the post’s wall, 00 on North. The plotter would put down a marker on the table and a simple triangulation with the markers from other posts would give a good plot.

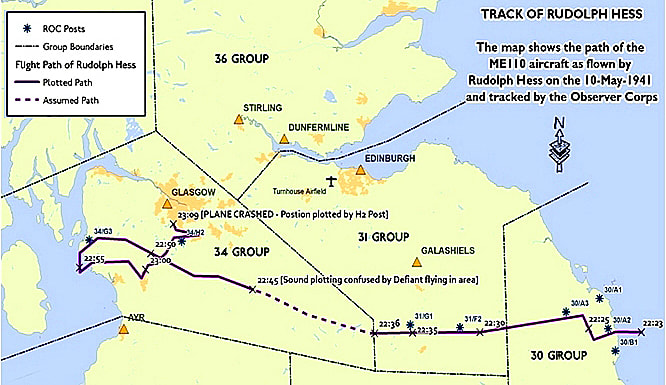

Even complicated courses changes could be followed. This is the weaving track of Rudolf Hess when he flew to Scotland hoping to contact the Duke of Hamilton and bring the war to an end.

Even complicated courses changes could be followed. This is the weaving track of Rudolf Hess when he flew to Scotland hoping to contact the Duke of Hamilton and bring the war to an end.

The first plots were made in the last evening light and the posts identified the aeroplane as an Me 110. This was promptly rejected by the RAF Filter Room on the grounds that an Me110 didn’t have the range to make a raid on Scotland. The rest of the flight was followed by sound plots. (The RAF did have the grace to ring the next day and apologise. It was followed by a letter of commendation for the observers who made the identification.)

|

The 12 Spitfires of 19 Sqn seem to be closing to intercept and it looks as if the controller has told the six Hurricanes of the Czech 310 Sqn to head west and climb for height.

The whole complex system of detection, identification and plotting was, of course, untested, other than in limited exercises, when war broke out. It was put to a real test in the first days of the war when almost everything that could go wrong, did. |

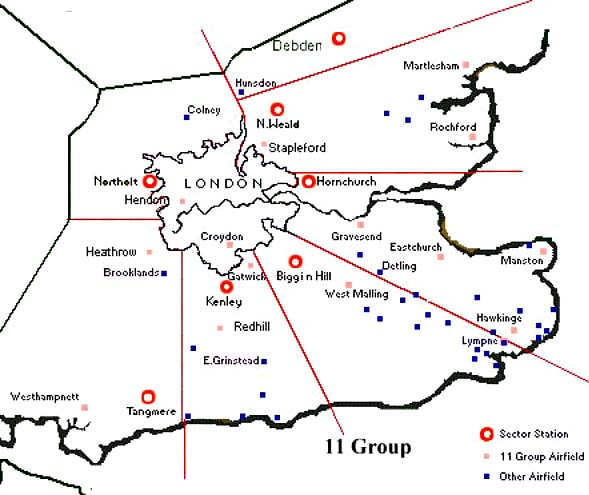

The final destination of the Observer Corps’ plots was the Controller’s table and all the preliminary organisation and work leads to this crucial point, The Controller had all the information he needed to direct the fighters to the point of interception. Every Sector of a Group had its own control room and these are 11 Group’s at the time of the BoB.

The picture below is of Duxford’s control room (It’s in a small building behind the hangars and open to visitors.) The markings are kept to a minimum. (Incidentally, no plotter worth her salt would tolerate such untidy placing). They show an incoming hostile raid - Hostile 67 - (30+ aircraft at 30,000’) heading north-west. |

The Battle of Barking Creek

WWII was only three days old. No one knew how, or when, the action would start. (Those warning sirens on the first day had been a false alarm - it was just a French plane coming from Paris). But all senses were keyed up - the Germans would be bound to come sooner or later.

The searchlight battery on Mersea Island coast was coming off duty. It was 6.15 am and the sun was up. Their habitual upward glance saw a gap in the clouds and there - yes, it was a formation of high-flying aircraft. They reported it immediately to Sector Ops Room at North Weald (off the Western edge of our map). At 6.18 am the Sector Controller, Gp Capt Lucking, informed the Observer Corps Centre at Colchester about ‘the raiders’. He also passed on the plot to 11 Group’s Ops Room at Uxbridge. 11 Group at Uxbridge informed 12 Group - Nottingham - about the raid. It could turn north into their area.

Both the Observer Corps and the radar stations reported no sightings or plots - yet.

At 6.30 am the Sector Controller at North Weald scrambled one flight of six Hurricanes from 56 Sqn at North Weald to patrol between Colchester and Harwich at 11,000ft (that’s ‘Angels eleven’ in the current R/T language). 56 Sqn’s CO, Sqn Ldr Knowles, decided to send 12 Hurricanes for good measure.

Both the Observer Corps and the radar stations reported no sightings or plots - yet.

At 6.30 am the Sector Controller at North Weald scrambled one flight of six Hurricanes from 56 Sqn at North Weald to patrol between Colchester and Harwich at 11,000ft (that’s ‘Angels eleven’ in the current R/T language). 56 Sqn’s CO, Sqn Ldr Knowles, decided to send 12 Hurricanes for good measure.

The squadron’s two reserve pilots didn’t want to miss out and on their own initiative they also took off five minutes after the others and chased after the formation. By 6.40 am the Sector Controller had learned that he had a full squadron of 12 Hurricanes in the air - he wasn’t told anything about the extra two semi-detached Hurricanes. At the Observer Corps Centre the plots coming in from the posts were of a formation of Hurricanes plus other as yet unidentified aircraft on the track of the raiders they‘d been warned about. At North Weald Lucking scrambled another 6 Hurricanes from 151 Sqn.

It was 6.50 am when the radar station at Canewden joined in with multiple plots of aircraft approaching from the east. 11 Group at Uxbridge reacted by scrambling four flights of Spitfires (two from 74 Sqn, one each from 64 and 54). They were given orders to climb to their ‘operational height’ i.e. higher than the Hurricanes. By now a Red Alert had been in place in Greater London and the air raid sirens were wailing again.

The first shots were fired by an anti-aircraft battery near Clacton. They were pretty sure it was a twin-engined aircraft - presumed hostile.

The Spitfires of 74 Sqn arrived from the west and saw a formation silhouetted against the morning sun. The flight leader, ‘Sailor’ Malan, called out ‘Bandits ahead!’ The shell bursts around two stragglers confirmed this identification and a section of three Spitfires dived in to attack - ‘Tally-ho, they cried.

It was not, of course, Bandits. It was 56 Sqn, breaking formation to escape from the flak. The Spitfires realised this only after they had shot down two of the Hurricanes. (One pilot died and the other had to force land his damaged Hurricane. Fortunately he was uninjured.)

The Hurricanes of 151, led by the squadron CO Sqn Ldr Teddy Donaldson* arrived. He looked down at the mass of (18) Hurricanes swirling around (24) Spitfires and called ’Do not retaliate. Bandits are friendly’.

*Edward Donaldson joined the RAF in 1931. He led 151 Sqn through the Battle of Britain (11 kills, 10 probables, DSO). In 1946 he took the World Air Speed Record in a Meteor and retired in 1961 as Air Commodore.

*Edward Donaldson joined the RAF in 1931. He led 151 Sqn through the Battle of Britain (11 kills, 10 probables, DSO). In 1946 he took the World Air Speed Record in a Meteor and retired in 1961 as Air Commodore.

The noises off in this temporary theatre of war were provided by the Controller at 12 Group. He scrambled two squadrons of Spitfires (19 and 66) from Duxford. In nil wind conditions they took off in all directions, which was the practice at the time. Several near collisions and many avoidances later they were subdued and recalled.

Meanwhile the ex-combatants over the Thames estuary sorted themselves out and headed for home, encouraged along the way by the still firing AA batteries at Sheerness and Thameshaven. Only one Spittfire was damaged and all landed safely.

The two Spitfire pilots who had shot down the Hurricanes were immediately arrested as was the luckless Gp Cpt Lucking. At the court of inquiry blame was spread far and wide. The original sighting of the ‘raiders’ was deemed to be a flock of seabirds coming home from a fishing trip, the ‘twin engined probably hostile’ could have been two Hurricanes or Spitfires flying close together and the radar plot of a formation coming in from the east was almost certainly a reciprocal - all direction finding by radio or radar (at the time) gave two directions, 180° different: the operator had to determine which one was correct.

The Spitfire pilots were cleared of blame. What happened to Lucking is unclear. Although he was acting as Sector Controller on the time, his day job was Station Commander at North Weald. The findings of the Court Martial are still locked to this day in a secret file. (He had joined the RNAS in 1917 as a Technical Offer and had served as Engineer or Technical Officer throughout his RAF career. His service records show that he was ‘Transferred to the Technical Branch’ in April 1940. He must have redeemed himself by being good at his normal job because he was promoted to Air Commodore in December 1941, a rank he held until his retirement in 1945.

News and tales of this incident spread rapidly and in the RAF it became known as the Battle of Barking Creek - which is some distance from the action but appropriately it is the place on the Thames estuary where there is a major release of sewage. The Ministry of Information released a statement to inform the general public that ‘Contact was not made with the enemy who turned back before reaching the coast. On returning some of our aircraft were mistaken for enemy aircraft which caused the coastal batteries to open fire.’ One of the crashed Hurricanes was mentioned - ‘The pilot of an RAF machine made a successful forced landing by the side of the road’. There was no reference to the other Hurricane, whose pilot had been shot dead before his Hurricane crashed.

(On 25th September The name of Plt Off Montague Hulton-Harrop of 56 Sqn appeared in a casualty list. He was listed as ‘killed in action’.)

Many lessons were learned from this ‘battle’. Inevitably mis-identification, double plotting and unnecessary scrambling occurred but never in combinations which produced such disastrous results. The Dowding System worked as it was meant to. The Observer Corps and the radar stations provided a flood of plots, the Filterers made sense of them and gave the Fighter Controllers an accurate picture of the air activity in his Sector. Every enemy attack was countered with a timely and effective defence.

Throughout the Battle of Britain the unpaid volunteers of the Observer Corps unfailingly provided a continuous series of plots of all aircraft flying over the country. If it could be seen - or heard - it was plotted.

Their sterling service during the Battle of Britain was recognised in February 1941 when the king granted royal status to the organisation and it became the Royal Observer Corps (and the Corps then allowed women to join).

The two Spitfire pilots who had shot down the Hurricanes were immediately arrested as was the luckless Gp Cpt Lucking. At the court of inquiry blame was spread far and wide. The original sighting of the ‘raiders’ was deemed to be a flock of seabirds coming home from a fishing trip, the ‘twin engined probably hostile’ could have been two Hurricanes or Spitfires flying close together and the radar plot of a formation coming in from the east was almost certainly a reciprocal - all direction finding by radio or radar (at the time) gave two directions, 180° different: the operator had to determine which one was correct.

The Spitfire pilots were cleared of blame. What happened to Lucking is unclear. Although he was acting as Sector Controller on the time, his day job was Station Commander at North Weald. The findings of the Court Martial are still locked to this day in a secret file. (He had joined the RNAS in 1917 as a Technical Offer and had served as Engineer or Technical Officer throughout his RAF career. His service records show that he was ‘Transferred to the Technical Branch’ in April 1940. He must have redeemed himself by being good at his normal job because he was promoted to Air Commodore in December 1941, a rank he held until his retirement in 1945.

News and tales of this incident spread rapidly and in the RAF it became known as the Battle of Barking Creek - which is some distance from the action but appropriately it is the place on the Thames estuary where there is a major release of sewage. The Ministry of Information released a statement to inform the general public that ‘Contact was not made with the enemy who turned back before reaching the coast. On returning some of our aircraft were mistaken for enemy aircraft which caused the coastal batteries to open fire.’ One of the crashed Hurricanes was mentioned - ‘The pilot of an RAF machine made a successful forced landing by the side of the road’. There was no reference to the other Hurricane, whose pilot had been shot dead before his Hurricane crashed.

(On 25th September The name of Plt Off Montague Hulton-Harrop of 56 Sqn appeared in a casualty list. He was listed as ‘killed in action’.)

Many lessons were learned from this ‘battle’. Inevitably mis-identification, double plotting and unnecessary scrambling occurred but never in combinations which produced such disastrous results. The Dowding System worked as it was meant to. The Observer Corps and the radar stations provided a flood of plots, the Filterers made sense of them and gave the Fighter Controllers an accurate picture of the air activity in his Sector. Every enemy attack was countered with a timely and effective defence.

Throughout the Battle of Britain the unpaid volunteers of the Observer Corps unfailingly provided a continuous series of plots of all aircraft flying over the country. If it could be seen - or heard - it was plotted.

Their sterling service during the Battle of Britain was recognised in February 1941 when the king granted royal status to the organisation and it became the Royal Observer Corps (and the Corps then allowed women to join).

The Battle was not the Corps’ only Big Moment. Before the June 1944 invasion - Operation Overlord - AVM Leigh Mallory suggested that Observers should be posted on landing craft and armed merchant ships with RN or US Navy gun crews to reduce incidents of ‘friendly fire’. There were over 1300 volunteers and in the event 796 were enrolled as temporary Petty Officers in the Royal Navy - pay £1 per day. They also swotted up on ship recognition.

They performed splendidly. Two were killed and one injured and 22 were rescued from sinking ships. Ten were mentioned in dispatches. After 2 - 3 months all were released and came home to wear the ‘Seaborne’ shoulder badge with pride.

They performed splendidly. Two were killed and one injured and 22 were rescued from sinking ships. Ten were mentioned in dispatches. After 2 - 3 months all were released and came home to wear the ‘Seaborne’ shoulder badge with pride.