Corsair Down (Dec 2020)

It had been a very early start. The passengers had been roused from their beds at 2.30 am. They had enough time to enjoy a ‘breakfast’, however hungry they were at that hour, before being taken down to the jetty to board the Corsair, a luxurious Short C class flying boat. It was all part of their five day journey on the Imperial Airways Empire route from South Africa to England, more of an adventure, really. For a charge of £125 – that’s the equivalent of about £2,500 today - they would take off in the early dawn, stopping for lunch, or tea, but primarily for fuel, before the last alighting of the day for an 'overnight' in a smart hotel.

Today, 14th March, 1939, they had lifted off from the eastern shore of the vast Lake Victoria at Kisumu in Kenya. Just over an hour later, they were again floating on the lake for a quick refuelling stop at Port Bell, near Entebbe, Uganda. The next leg was a 325 mile flight across the Sudd, a huge swampy wetland where the outflow from Lake Victoria forms a sort of inland delta with meandering streams. When it becomes a navigable river again it is the Nile and on its banks is Juba in the Sudan, the next overnight stop.

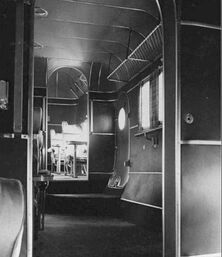

Beyond the promenade

deck is the aft cabin.

Beyond the promenade

deck is the aft cabin.

It was hardly a sight-seeing flight. The passengers were encouraged to move around and take advantage of the views from the generously windowed ‘promenade’. However, the weather had turned and the Corsair was flying mostly in cloud. With so little of interest to look at many of the passengers were asleep. As was the pilot. The C class boats were one of the first British commercial aeroplanes to have an auto-pilot and it was switched on when the captain climbed into the bunk in the crew’s cubbyhole by the main spar. He needed to be wide awake for the landing at Juba.

The captain had a famous name. He was Edward Alcock. His older brother, Sir John Alcock, had been knighted for his non-stop transatlantic flight in 1919, the world’s first. He had tragically died in a crash just six months later. Now Edward was called ‘John’ by all his colleagues.

The captain had a famous name. He was Edward Alcock. His older brother, Sir John Alcock, had been knighted for his non-stop transatlantic flight in 1919, the world’s first. He had tragically died in a crash just six months later. Now Edward was called ‘John’ by all his colleagues.

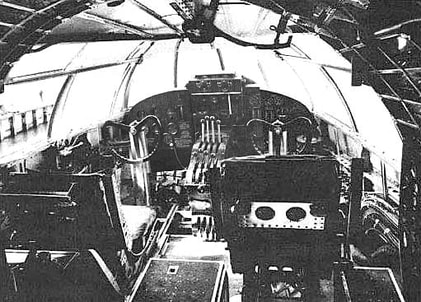

The captain woke after his nap and went forward to the spacious control cabin where the co-pilot and wireless operator were in relaxed conversation. Alcock asked for a bearing on Juba. There had been a problem with the direction finding aerial the previous day but the unit had been replaced by the engineers at Kisumu. So they believed it when the radio officer surprisingly announced that they were ‘past it’.

They promptly reversed course and studied the ground through the holes in the cloud cover. They could see only swamp or trees – nothing which would clarify their position.

For two hours they tracked back and forth becoming increasingly suspicious of the bearings the D/F was giving and even suspecting a fault with the compass. There was only 15 minutes of fuel left when they saw a twisting river below them.

They promptly reversed course and studied the ground through the holes in the cloud cover. They could see only swamp or trees – nothing which would clarify their position.

For two hours they tracked back and forth becoming increasingly suspicious of the bearings the D/F was giving and even suspecting a fault with the compass. There was only 15 minutes of fuel left when they saw a twisting river below them.

Alcock found the longest straightish stretch of the river and approached as slowly as he dared. The river was little wider than Corsair’s wingspan. He skilfully lowered Corsair into mid-stream and steered carefully round a bend.

As the boat slowed, he thought he had achieved a successful alighting. Then they crashed into a submerged rock. It ripped a hole in the hull. Alcock slammed open the throttles and steered for the bank, jamming the boat up onto the mud. No-one had warned the passengers of their emergency landing and some had slept through it all. It was the crash into the rock and the roar of the engines which had woken them.

As the boat slowed, he thought he had achieved a successful alighting. Then they crashed into a submerged rock. It ripped a hole in the hull. Alcock slammed open the throttles and steered for the bank, jamming the boat up onto the mud. No-one had warned the passengers of their emergency landing and some had slept through it all. It was the crash into the rock and the roar of the engines which had woken them.

Rather than submit the passengers to the indignity of crawling through the bow compartment to its small hatch the crew cut a hole in the roof of the cockpit. The thirteen passengers, all uninjured, scrambled out of the wreck onto the river bank.

The question everyone asked, ‘Where are we?’ was soon answered. A car drove up and a white man emerged. He introduced himself as M. Appermans, a Belgian, who happened to be the local district commissioner. He lived some distance away and had watched Corsair circling.

The question everyone asked, ‘Where are we?’ was soon answered. A car drove up and a white man emerged. He introduced himself as M. Appermans, a Belgian, who happened to be the local district commissioner. He lived some distance away and had watched Corsair circling.

He told them they had alighted on the River Dungu. They were in the Belgian Congo, several miles from the small town of Faradje and 200 miles from Juba.

The only one hurt when Corsair crashed into the rock was the Radio Officer who had struck his head and was temporarily dazed. But he recovered sufficiently to spend the next three hours swimming about collecting mail, luggage and other valuables from the semi-submerged boat. He also found out why they were in the Congo,

He discovered that the D/F unit had been serviceable all along. However, the engineers had connected it with reversed polarity. This meant that all the bearings were incorrect by precisely180º.

The only one hurt when Corsair crashed into the rock was the Radio Officer who had struck his head and was temporarily dazed. But he recovered sufficiently to spend the next three hours swimming about collecting mail, luggage and other valuables from the semi-submerged boat. He also found out why they were in the Congo,

He discovered that the D/F unit had been serviceable all along. However, the engineers had connected it with reversed polarity. This meant that all the bearings were incorrect by precisely180º.

M. Appermanns took everyone to his home and supplied them all with food and drink. Some passengers (who included the sister of the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain) needed slippers to replace their water damaged shoes. All needed umbrellas or sun helmets hats to protect them from the fierce sun. Transport was arranged (there was no road, just tracks or tyre marks) to take the passengers, mail and luggage the 50 miles to Aba, on the Sudan border. From there Imperial Airways took them to Juba where, two days later, they caught Centurion, the next northbound flight. (In a sad after comment it was noted that M. and Mde. Appermanns were given no recompense, nor were any of the loaned items returned. When they heard about this, Imperial Airways arranged free return flights for the Appermanns to visit Europe).

In 1937 forty two C class boats had been ordered from Short Bros. by Imperial Airways and they were all in use on the three great ‘Empire’ routes – England to South Africa, to Australia and across the Atlantic. There had been serious attrition. Cygnus crashed in Italy, Centurion at Batavia, Cavalier in the Atlantic and Connemara was lost in a fire on Southampton Water. Altogether seven boats had been written off and Corsair was sorely needed. It was just two years old and replacing it with a new one wasn’t possible. Britain’s re-armament programme was keeping Shorts fully occupied producing Sunderlands. It was unthinkable that the boat should be abandoned because of a holed hull.

Reconnaissance by an RAF Wellesley had pin-pointed Corsair’s exact position. Hugh Gordon, one of Shorts’ engineers who was repairing another boat which had taxied into a submarine in Naples harbour was ordered to catch the next boat flying to Juba then inspect Corsair to see what was needed to repair it. ‘Frames 12 – 25 inclusive extensively damaged including keel plating, stringers and floor supports for 24 feet’ was part of his report. If everything went well, he thought the repair would take ’about six weeks’.

Back in England he assembled his team of five engineers, tools and spares. In Africa they hired two Ford station wagons and in Juba picked up a radio operator to keep in contact with the outside world using Corsair’s radio and Morse messages.

In 1937 forty two C class boats had been ordered from Short Bros. by Imperial Airways and they were all in use on the three great ‘Empire’ routes – England to South Africa, to Australia and across the Atlantic. There had been serious attrition. Cygnus crashed in Italy, Centurion at Batavia, Cavalier in the Atlantic and Connemara was lost in a fire on Southampton Water. Altogether seven boats had been written off and Corsair was sorely needed. It was just two years old and replacing it with a new one wasn’t possible. Britain’s re-armament programme was keeping Shorts fully occupied producing Sunderlands. It was unthinkable that the boat should be abandoned because of a holed hull.

Reconnaissance by an RAF Wellesley had pin-pointed Corsair’s exact position. Hugh Gordon, one of Shorts’ engineers who was repairing another boat which had taxied into a submarine in Naples harbour was ordered to catch the next boat flying to Juba then inspect Corsair to see what was needed to repair it. ‘Frames 12 – 25 inclusive extensively damaged including keel plating, stringers and floor supports for 24 feet’ was part of his report. If everything went well, he thought the repair would take ’about six weeks’.

Back in England he assembled his team of five engineers, tools and spares. In Africa they hired two Ford station wagons and in Juba picked up a radio operator to keep in contact with the outside world using Corsair’s radio and Morse messages.

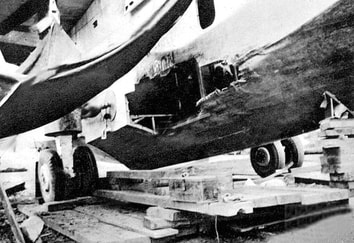

The first and biggest problem was getting Corsair out of the water. Through M. Appermanns Gordon hired a gang of local men (for ridiculously cheap wages) to build a coffer dam and lower the water level around the boat. Mud was dug out to sink in logs of dense and heavy iron wood on which the hydraulic jacks would stand. The boat was then lifted onto its beaching wheels which would run on a ramp – more iron wood of course. At last over a hundred Africans hauled on ropes and Corsair was raised to level ground.

This work was helped enormously by a figure who emerged from a mud-covered group of workers and introduced himself, in an American accent, as the Rev Harry Stam, originally from New Jersey, now from a Mission in the depths of the Congo. He spoke Lingala, the local language and was much more effective in instructing the workers than the shouting and waving of Hugh Gordon. He also organised much better food. The engineers ate no more snake sandwiches.

This work was helped enormously by a figure who emerged from a mud-covered group of workers and introduced himself, in an American accent, as the Rev Harry Stam, originally from New Jersey, now from a Mission in the depths of the Congo. He spoke Lingala, the local language and was much more effective in instructing the workers than the shouting and waving of Hugh Gordon. He also organised much better food. The engineers ate no more snake sandwiches.

The repair work could now begin. Almost immediately, all the power tools broke down and all drilling and riveting had to be done by hand. One African was employed just to blow away the swarf from the drill. The dam builders turned to widening the river by cutting away elephant grass and felling the odd tree.

Back in England, ‘John’ Alcock ironically had been assigned to flying Corsair out of the Congo. Apparently someone had said ‘He put it there, he can get it out’. He spent some time practising take offs in Southampton Water with a lightly loaded boat, calculating the distance required in various wind speeds.

Back in England, ‘John’ Alcock ironically had been assigned to flying Corsair out of the Congo. Apparently someone had said ‘He put it there, he can get it out’. He spent some time practising take offs in Southampton Water with a lightly loaded boat, calculating the distance required in various wind speeds.

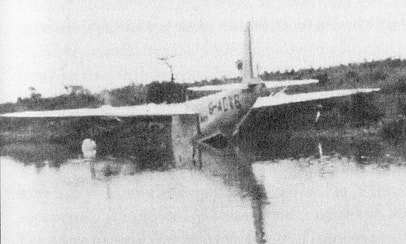

When Corsair was finally back in the river they waited for the river level to rise. It should have been much higher at that time of year. Perversely it was falling. Nevertheless, Alcock and his co-pilot travelled to Africa. Everything not essential for flying was taken out of the boat – Harry Stam’s mission got some beautiful porcelain hand basins. They managed to get the weight down to 13 tons.

Alcock was worried about the rock he had collided with when he landed in March. He was assured it had been blasted by some engineers from a gold mine and was now 14 inches below the surface. At that point in the take off the boat would be on the step and planing. But he’d hit the rock only because he steered away from rocks on the other side of the river. These were marked by driving in saplings on which white streamers were attached. A take off path was worked out so that there would be 20 feet between the port float and the bank and 20 feet between the hull and the marked rocks – the float would pass over them. Still the river remained low.

At last, on the night of 13th July it rained for three hours and the river rose 6 inches. Take off would be first thing the next morning.

0605 hours, cool (for the Congo), damp, river current 2½ knots. Corsair sat on the water running its engines, tied by a rope to a tree on the bank to stop it drifting downstream. It was exactly four months since it had touched down here on the Dungu. Gordon and his engineers were stationed at intervals along the bank to signal if the boat deviated from its chosen path.

The rope was slipped and Alcock opened the throttles. Within 50 yards Corsair was rising on the step. Then it all went wrong. The boat began to swing to starboard. Alcock could only reduce power on the port engine.

When the starboard float began hitting the bank Alcock cut the engines. Corsair settled, swung towards the bank and the hull stuck the rock which it had avoided on the first landing. The co-pilot stuck his head through the window and shouted ‘It was the outer engine!’

In the aftermath it seems that the starboard engines were blamed for loss of power, but it might have been a change in the current after a bend in the river. The Central Africa manager said Alcock had defied instructions by attempting a take off when the water levels were too low. Alcock declared that he was washing his hands of the whole affair – and left.

Alcock was worried about the rock he had collided with when he landed in March. He was assured it had been blasted by some engineers from a gold mine and was now 14 inches below the surface. At that point in the take off the boat would be on the step and planing. But he’d hit the rock only because he steered away from rocks on the other side of the river. These were marked by driving in saplings on which white streamers were attached. A take off path was worked out so that there would be 20 feet between the port float and the bank and 20 feet between the hull and the marked rocks – the float would pass over them. Still the river remained low.

At last, on the night of 13th July it rained for three hours and the river rose 6 inches. Take off would be first thing the next morning.

0605 hours, cool (for the Congo), damp, river current 2½ knots. Corsair sat on the water running its engines, tied by a rope to a tree on the bank to stop it drifting downstream. It was exactly four months since it had touched down here on the Dungu. Gordon and his engineers were stationed at intervals along the bank to signal if the boat deviated from its chosen path.

The rope was slipped and Alcock opened the throttles. Within 50 yards Corsair was rising on the step. Then it all went wrong. The boat began to swing to starboard. Alcock could only reduce power on the port engine.

When the starboard float began hitting the bank Alcock cut the engines. Corsair settled, swung towards the bank and the hull stuck the rock which it had avoided on the first landing. The co-pilot stuck his head through the window and shouted ‘It was the outer engine!’

In the aftermath it seems that the starboard engines were blamed for loss of power, but it might have been a change in the current after a bend in the river. The Central Africa manager said Alcock had defied instructions by attempting a take off when the water levels were too low. Alcock declared that he was washing his hands of the whole affair – and left.

And then, the river began to rise. Corsair had a new hole 11 feet long, it was flooded by the rising water and now stuck on the opposite side of the river from the iron wood ramp. The Shorts team were called home. Hugh Gordon couldn’t leave. His job to salvage Corsair wasn’t finished. He was grateful that Peter Newnham, one of his engineers came back to help him.

The rising river brought new dangers, the real threat of dysentery and bilharzia. The native refused to work in the flooded hull because of ‘serpents’, water snakes, and there could be crocodiles. Help came from an unlikely source.

They had been visited from time to time by a man who worked for a Belgian company which provided services for the scattered mining companies. Although his name was Lacovich he was Italian and ran his company’s workshop. He knocked up a sort of unpressurised diving suit for Gordon to use whilst he tried to fit a temporary patch inside the hull. The aim was to float Corsair across the river to the slipway.

All work stopped when suddenly Gordon and Newnham were ordered to go home – no arguments. War had been declared.

Imperial Airways were now the only people with any interest in Corsair. Roy Sisson was their ground engineer in Alexandria. ‘There’s a bit of a problem down in the Congo’ he was told. Take a team of five engineers, remove the engines and any other parts suitable for spares then blow up the hulk.

The rising river brought new dangers, the real threat of dysentery and bilharzia. The native refused to work in the flooded hull because of ‘serpents’, water snakes, and there could be crocodiles. Help came from an unlikely source.

They had been visited from time to time by a man who worked for a Belgian company which provided services for the scattered mining companies. Although his name was Lacovich he was Italian and ran his company’s workshop. He knocked up a sort of unpressurised diving suit for Gordon to use whilst he tried to fit a temporary patch inside the hull. The aim was to float Corsair across the river to the slipway.

All work stopped when suddenly Gordon and Newnham were ordered to go home – no arguments. War had been declared.

Imperial Airways were now the only people with any interest in Corsair. Roy Sisson was their ground engineer in Alexandria. ‘There’s a bit of a problem down in the Congo’ he was told. Take a team of five engineers, remove the engines and any other parts suitable for spares then blow up the hulk.

When Sisson saw the state of the boat he realised that it had to come off the rock. They began lightening Corsair by removing heavy parts. First the engines, then the flaps and other parts.

They managed to get some huge tanks, each of 1000 gallons capacity, from a couple of old petrol tanker lorries. These were slid under the wings. They put a temporary patch on the hull and began pumping water out of Corsair. Three days later, at last, on 5th October Corsair gently rose and floated again. It was towed across to the ramp and hauled out of the river.

It seemed that the valuable boat could be repaired and flown out after all. Imperial Airways appointed a man to do it. He was Jack Kelly-Rogers, their most experienced captain, a strong personality with a reputation for getting difficult things done.

They managed to get some huge tanks, each of 1000 gallons capacity, from a couple of old petrol tanker lorries. These were slid under the wings. They put a temporary patch on the hull and began pumping water out of Corsair. Three days later, at last, on 5th October Corsair gently rose and floated again. It was towed across to the ramp and hauled out of the river.

It seemed that the valuable boat could be repaired and flown out after all. Imperial Airways appointed a man to do it. He was Jack Kelly-Rogers, their most experienced captain, a strong personality with a reputation for getting difficult things done.

Kelly-Rogers arrived at the Dungu camp on 2nd December. The river was low again. K-R lined up the engineers across the river (the Africans had refused to take any part in this) and got them to walk down the river, occasionally ankle deep, occasionally with only a floating topee visible. They discovered far too many rocks to allow a safe take off even if the river rose. And the rains weren’t due until April.

Within two days Kelly-Rogers had visited Kilo Moto, a diamond mine company at Watsa. In a masterstroke of organisation he arranged for them to build a dam across the Dungu for £165. (23,000 Belgian francs sounded more).

Within two days Kelly-Rogers had visited Kilo Moto, a diamond mine company at Watsa. In a masterstroke of organisation he arranged for them to build a dam across the Dungu for £165. (23,000 Belgian francs sounded more).

They calculated that it would have to be built further downstream where there were enough trees to provide the 20 tons of wood needed. It would be 72 metres across and need 170 tons of stone, mostly brought in by lorries. Kilo Moto would appoint four African foremen to control the labour force which would be provided, free, by the Belgian authorities - 200 convicts from various prisons. In preparation for the work to begin the Imperial Airways engineers changed profession and began ’jungle hacking’ to clear several miles of tracks for the lorries and then space for the erection of twenty or more buildings, largely grass, for the convicts to live in. This village soon acquired a name – Corsairville.

Corsair itself was quickly repaired, its engines serviced and refitted and it was ready for flight. The locals who had helped Hugh Gordon re-appeared. Lacovich insisted on helping with the servicing of the engines and every week an old Chevvy, emblazoned with ‘Jesus is Coming’ would turn up bringing a specially prepared dinner.

The dam was completed by the end of December and Corsair pulled into the river. After a riotous Christmas party Sisson and his team, rather reluctantly, left for Alexandria.

At 7.15 am on 6th January, 1940, the river banks were lined with hundreds of people to watch Kelly Rogers negotiate one bend in the river before speeding across the lake and lifting Corsair into the air. He circled once and rocked his wings to say a last goodbye to the Dungu and Corsairville.

Corsair returned to service but now it was wartime. Imperial Airways became BOAC and its boats carried mail and some passengers and many of the fleet were chartered to the RAF and the RAAF.

After the war airlines used landplanes. Even in the most remote parts of the world flying boats could not claim to have a monopoly of landing (alighting) places. Almost all the old Empire boats faded into history by being scrapped.

And here is Corsair at Hythe, retreating from the water for the very last time on a cold, cheerless 20th January 1947.

Vale Corsair