The First Flight Over Everest (June 2010)

Tucked in a corner at the back of one of Shuttleworth’s hangars is this fuselage skeleton. It doesn’t attract much attention but is a reminder of a significant historical event. A product of Skysport Engineering at Hatch, it was made to the order of one George Almond who hoped to raise funds for a television production. This would cover the re-enactment of the first flight over Everest, to be screened in 2003, the 70th anniversary of the flight. The funds didn’t materialise and the film was never made. Shuttleworth is the beneficiary and it is an appropriate place to store this relic.

The highest mountain in the world began to attract the attention of serious mountaineers from the beginning of the 20th Century. It was difficult to get there. Nepal, on the south side, was a closed country and Tibet, to the north, allowed limited access. A British army survey team was allowed to approach the north side in 1904 and a Captain Noel carried out a lone reconnaissance in 1913.

The war intervened and it wasn’t until 1919 that Noel could tell his story to the Royal Geographical Society. This led to another reconnaissance in 1921 and to serious attempts to climb Everest via the North face in 1922 and again in 1924 when George Mallory and Andrew Irvine died near the summit.

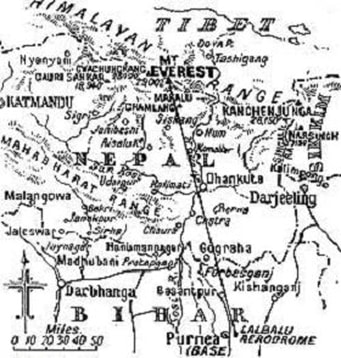

The idea of using aeroplanes to conquer Everest seems to have come from L V Stewart Blacker, a Major in the Indian Army and whose ancestor had been Surveyor-General of India. When he learned in 1932 that Flt Lt Uwins had set a world altitude record of 43,976 ft using Bristol’s supercharged Pegasus engine Blacker saw that a flight over Everest at 33,000 ft was practicable. Permission was granted by the Maharajah of Nepal for two flights over the country. A convenient British army landing ground at Lalbalu in Bihar, India, was available, some 260 miles north of Calcutta and 160 miles south east of the mountain. Although support for the expedition came from the Air Ministry and industry more money was needed. Lady Houston, who had previously financed the successful Schneider Trophy team in 1931, again came to the rescue.

The idea of using aeroplanes to conquer Everest seems to have come from L V Stewart Blacker, a Major in the Indian Army and whose ancestor had been Surveyor-General of India. When he learned in 1932 that Flt Lt Uwins had set a world altitude record of 43,976 ft using Bristol’s supercharged Pegasus engine Blacker saw that a flight over Everest at 33,000 ft was practicable. Permission was granted by the Maharajah of Nepal for two flights over the country. A convenient British army landing ground at Lalbalu in Bihar, India, was available, some 260 miles north of Calcutta and 160 miles south east of the mountain. Although support for the expedition came from the Air Ministry and industry more money was needed. Lady Houston, who had previously financed the successful Schneider Trophy team in 1931, again came to the rescue.

The aeroplanes chosen were the Westland Wallace, a two-seat general purpose biplane and the similar Westland PV3, a development with a split undercarriage intended to carry torpedoes. Both were powered by the Bristol Pegasus 550 hp engine. The team was led by Air Comm P F M Fellowes and Blacker, now a Lt Colonel, was Chief Observer and still photographer. An intensive period of work followed, developing practical oxygen systems, heated clothing and suitable cameras.

The Westlands were crated and shipped to Karachi. Fellowes, with his wife and some other team members decided to fly their own aeroplanes to India. They left in a DH Gypsy Moth, a Puss Moth and a Fox Moth, via Tunisia, Egypt, Iraq, Persia, sandstorms and bureaucracy. By 22 March 1933 they were united with the Westlands at Karachi and all flew across India to their base at Lalbalu.

Now they waited for suitable weather, ideally, clear skies and winds no stronger than 40 mph. This began to appear increasingly unlikely when measurement of wind speeds at 25,000 ft were found to average 70 mph.

On the 3rd April, Fellowes took an early morning flight to 17,000 ft in one of the Moths. He saw the mountain to be free of cloud and, although the forecast for upper wind was 58 mph he decided to go.

The Westland PV3 was piloted by Sqn Ldr the Marquess of Douglas and Clydesdale (the same Douglas Douglas-Hamilton whom Rudolf Hess hoped to meet in Scotland in 1941) with Blacker as observer. Flying the Wallace was Flt Lt MacIntyre with S R Bonnett, a Gaumont-British film cameraman, as observer. They emerged from the haze at 19,000 ft and found that the strong cross-wind from the west meant that they would approach the peaks from the leeward side. Blacker took a continuous series of photographs, changing the plates on a survey camera in the floor hatch and using a hand-held film camera in the open cockpit - all the time trying to avoid entanglement in oxygen pipes and electrical wires.

On the 3rd April, Fellowes took an early morning flight to 17,000 ft in one of the Moths. He saw the mountain to be free of cloud and, although the forecast for upper wind was 58 mph he decided to go.

The Westland PV3 was piloted by Sqn Ldr the Marquess of Douglas and Clydesdale (the same Douglas Douglas-Hamilton whom Rudolf Hess hoped to meet in Scotland in 1941) with Blacker as observer. Flying the Wallace was Flt Lt MacIntyre with S R Bonnett, a Gaumont-British film cameraman, as observer. They emerged from the haze at 19,000 ft and found that the strong cross-wind from the west meant that they would approach the peaks from the leeward side. Blacker took a continuous series of photographs, changing the plates on a survey camera in the floor hatch and using a hand-held film camera in the open cockpit - all the time trying to avoid entanglement in oxygen pipes and electrical wires.

Clydesdale described the final moments of the approach in ‘The Pilot’s Book of Everest’.

“We were in a tremendous down-rush of air. Though the machine continued to climb, it was climbing in an air current that was carrying it down at much greater velocity. Two thousand feet were lost before the down-rush cushioned itself out on the glacier beds.

“We were in a serious position. The great bulk of Everest was towering above us to the left, Makalu down-wind to the right and the connecting range dead ahead, with a hurricane wind doing its best to carry us over and dash us on the knife-edge side of Makalu.

“We were in a tremendous down-rush of air. Though the machine continued to climb, it was climbing in an air current that was carrying it down at much greater velocity. Two thousand feet were lost before the down-rush cushioned itself out on the glacier beds.

“We were in a serious position. The great bulk of Everest was towering above us to the left, Makalu down-wind to the right and the connecting range dead ahead, with a hurricane wind doing its best to carry us over and dash us on the knife-edge side of Makalu.

“I had the feeling that we were hemmed in on all sides, and that we dare not turn away to gain height afresh. There was plenty of air-space behind us, yet it was impossible to turn back. A turn to the left meant going back into the down-current and the peaks below; a down-turn round to the right would have taken us almost instantly into Makalu at 200 miles per hour.

“There was nothing we could do but climb straight ahead and hope to clear the lowest point in the barrier range. . . . With the aircraft heading almost straight into the wind, we crabbed sideways towards the ridge, unable to determine if we were level with it or below.”

They cleared the summit by little more than 100 feet and were rewarded with 15 minutes of smooth flying and close-up photography of Everest before heading for home.

“There was nothing we could do but climb straight ahead and hope to clear the lowest point in the barrier range. . . . With the aircraft heading almost straight into the wind, we crabbed sideways towards the ridge, unable to determine if we were level with it or below.”

They cleared the summit by little more than 100 feet and were rewarded with 15 minutes of smooth flying and close-up photography of Everest before heading for home.

Meanwhile, in the Wallace, Bonnett trod on his oxygen hose and split the pipe. He tied a handkerchief around the split but soon fell unconscious to the floor of the cockpit.

McIntyre, turning to check on Bonnett, disconnected his own oxygen mask. For the rest of the flight he had to hold it in place with one hand. He lost height as quickly as possible and at about 8,000 ft he noticed Bonnett “struggling up from the floor tearing off his mask and headgear. He was a nasty dark green shade but obviously alive and that was enough for the moment.”

Everest had been conquered but the photography was not a success. Bonnett had been unconscious for half the flight and the dust haze had made the survey photographs useless. Kanchenjunga, 90 miles east of Everest was in clearer air and could be approached without flying over Nepal so a flight was planned the next day to check all the equipment.

Fellowes flew the Wallace with A L Fisher and Fg Off R C W Ellison piloted the PV3 with Bonnet. They met severe turbulence over the peaks and the weather was so cloudy that the aeroplanes lost contact with each other. Fellowes had trouble with his oxygen mask and became vague about his navigation. Through the haze he found a railway line and landed by a station to find he was some distance east of Lalbalu. With difficulty he managed to get clear of the throng of people and animals and take off. Insufficient fuel to get home brought about his second emergency landing. A telegram re-assured his colleagues that he was safe and next day one of the Moths brought fuel and a starting handle.

Back in England, the general view was that enough was enough and that it would be foolhardy to attempt the second flight over Everest. Lady Houston said “Do not tempt the evil spirits of the mountain to bring disaster”. The insurers insisted that their obligation to cover two flights had now been met and asked for a further £600 premium for another flight. The weather worsened. Fellowes went down with a fever and the meteorologist and one of his assistants was badly burnt when a weather balloon exploded.

However . . . on 19th April the weather was fine, although the winds were forecast at 88 mph - and there was enough oxygen. The original crews planned a flight, intending to aim to the west of Everest and delay their climb to height to counter the strongest wind. They said nothing to Fellowes who was still in his sick-bed when took off.

McIntyre, turning to check on Bonnett, disconnected his own oxygen mask. For the rest of the flight he had to hold it in place with one hand. He lost height as quickly as possible and at about 8,000 ft he noticed Bonnett “struggling up from the floor tearing off his mask and headgear. He was a nasty dark green shade but obviously alive and that was enough for the moment.”

Everest had been conquered but the photography was not a success. Bonnett had been unconscious for half the flight and the dust haze had made the survey photographs useless. Kanchenjunga, 90 miles east of Everest was in clearer air and could be approached without flying over Nepal so a flight was planned the next day to check all the equipment.

Fellowes flew the Wallace with A L Fisher and Fg Off R C W Ellison piloted the PV3 with Bonnet. They met severe turbulence over the peaks and the weather was so cloudy that the aeroplanes lost contact with each other. Fellowes had trouble with his oxygen mask and became vague about his navigation. Through the haze he found a railway line and landed by a station to find he was some distance east of Lalbalu. With difficulty he managed to get clear of the throng of people and animals and take off. Insufficient fuel to get home brought about his second emergency landing. A telegram re-assured his colleagues that he was safe and next day one of the Moths brought fuel and a starting handle.

Back in England, the general view was that enough was enough and that it would be foolhardy to attempt the second flight over Everest. Lady Houston said “Do not tempt the evil spirits of the mountain to bring disaster”. The insurers insisted that their obligation to cover two flights had now been met and asked for a further £600 premium for another flight. The weather worsened. Fellowes went down with a fever and the meteorologist and one of his assistants was badly burnt when a weather balloon exploded.

However . . . on 19th April the weather was fine, although the winds were forecast at 88 mph - and there was enough oxygen. The original crews planned a flight, intending to aim to the west of Everest and delay their climb to height to counter the strongest wind. They said nothing to Fellowes who was still in his sick-bed when took off.

MacIntyre wrote “There on my right was the enormous pinnacle, the bright morning sun glinting on the frozen snow and throwing into strong relief the great rock faces, some of them a sheer 8,000 feet or more.

“The next fifteen minutes was a grim struggle. The altimeter showed 34,000 feet. The menacing peak with its enormous plume whirling and streaking away to the South-East at 120 miles an hour appeared to be almost underneath us but refused to get right beneath. After what seemed an interminable time, it disappeared below the nose of the aircraft. I determined to hold the compass course until I gauged we were just over the mountain. Petrol was getting low and I knew there would not be sufficient to go beyond.

“We appeared to be stationary. I cast quick, anxious glances behind and below to see if we had passed over. Then suddenly there was a terrific bump—just one terrific impact such as one might receive flying over an explosives factory as it blew up.

“The next fifteen minutes was a grim struggle. The altimeter showed 34,000 feet. The menacing peak with its enormous plume whirling and streaking away to the South-East at 120 miles an hour appeared to be almost underneath us but refused to get right beneath. After what seemed an interminable time, it disappeared below the nose of the aircraft. I determined to hold the compass course until I gauged we were just over the mountain. Petrol was getting low and I knew there would not be sufficient to go beyond.

“We appeared to be stationary. I cast quick, anxious glances behind and below to see if we had passed over. Then suddenly there was a terrific bump—just one terrific impact such as one might receive flying over an explosives factory as it blew up.

“It felt as if the wings should break off at the roots, but there was no nasty cracking noise such as would have denoted structural failure. A hurried look round showed every wire taut. There was no sign of slackness anywhere. The bump was a relief in a way, as it indicated the summit and was the signal for a careful, gentle turn to the right to settle down on our predetermined compass course for home.”

At first Fellowes was furious at the insubordination of his team and their use of the uninsured aeroplanes but they had returned safely from a completely successful flight with perfect photographs. Congratulations flowed in from the Chief of the Air Staff, from the press and the public. The team returned home in triumph.

At first Fellowes was furious at the insubordination of his team and their use of the uninsured aeroplanes but they had returned safely from a completely successful flight with perfect photographs. Congratulations flowed in from the Chief of the Air Staff, from the press and the public. The team returned home in triumph.