Supermarine Stranraer (July 2018)

(and Hughie Green)

Despite being a design of the famed R J Mitchell the Stranraer never made much of an impact on the aviation scene. Its predecessor, the Southampton, had been reasonably successful and in 1931 the Air Ministry issued Specification R 20/31 for its replacement.

Supermarine had been experimenting to improve the aerodynamics and hydrodynamics of the complex and very draggy flying boat structure and tried major modifications to the Southampton, to earlier boats and a private venture luxury Air Yacht. At one time they were juggling no fewer than five possible layouts, using two, three, four and even six engines chosen from at least five different types of engine. To add interest, they were replacing some of the previous wooden structures with metal, which added different flat plate shapes to the hulls. Supermarine offered what they said was an improved version of the Southampton, they called it the Mk IV. The Air Ministry looked at the prototype, quite liked it and re-wrote the specification.

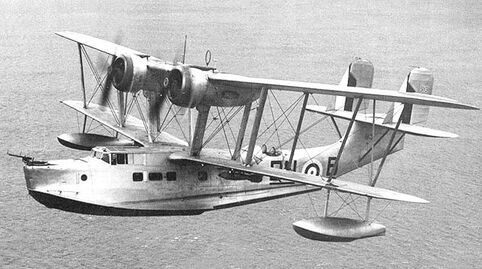

The first flight of the Stranraer, named after an obscure, not easy to spell ferry port in the south-west corner of Scotland, was on 27 July 1934. When tests were completed it was delivered to the RAF on 29 October. Press releases said ‘it passed its tests brilliantly’ although no actual performance figures were released. In August 1935 an order was placed for 17 and the first production model entered service on 16 April 1937.

Powered by two 820 hp Bristol Pegasus engine it was of all-metal construction although with fabric-covered wings. The single-skinned hull was made from a new magnesium-aluminium alloy saving over 900 lbs weight compared with the old double-skinned wooden hulls which gained more weight with water soakage. The pilots sat in an enclosed cabin protected from spray, the gun positions had hatches and the tail gunner had a windscreen.

Supermarine had been experimenting to improve the aerodynamics and hydrodynamics of the complex and very draggy flying boat structure and tried major modifications to the Southampton, to earlier boats and a private venture luxury Air Yacht. At one time they were juggling no fewer than five possible layouts, using two, three, four and even six engines chosen from at least five different types of engine. To add interest, they were replacing some of the previous wooden structures with metal, which added different flat plate shapes to the hulls. Supermarine offered what they said was an improved version of the Southampton, they called it the Mk IV. The Air Ministry looked at the prototype, quite liked it and re-wrote the specification.

The first flight of the Stranraer, named after an obscure, not easy to spell ferry port in the south-west corner of Scotland, was on 27 July 1934. When tests were completed it was delivered to the RAF on 29 October. Press releases said ‘it passed its tests brilliantly’ although no actual performance figures were released. In August 1935 an order was placed for 17 and the first production model entered service on 16 April 1937.

Powered by two 820 hp Bristol Pegasus engine it was of all-metal construction although with fabric-covered wings. The single-skinned hull was made from a new magnesium-aluminium alloy saving over 900 lbs weight compared with the old double-skinned wooden hulls which gained more weight with water soakage. The pilots sat in an enclosed cabin protected from spray, the gun positions had hatches and the tail gunner had a windscreen.

When the prototype’s engines were upgraded to 920 hp driving three blade metal propellers the Stranraer was hailed as the RAF’s fastest flying boat. True, but comparisons are odious. Its maximum speed was 165 mph.

Production began, but not at a high rate. The works were busy and overcrowded and there were competing priorities. The majority of workers were building Spitfires.

After all the hype, the crews were not over impressed by their new machine. It soon acquired a number of derisory nicknames – the ‘Flying Meccano Set’ and ‘The Strainer’.

Production began, but not at a high rate. The works were busy and overcrowded and there were competing priorities. The majority of workers were building Spitfires.

After all the hype, the crews were not over impressed by their new machine. It soon acquired a number of derisory nicknames – the ‘Flying Meccano Set’ and ‘The Strainer’.

One of its innovations was the fitting of a toilet, actually just a vent which opened directly to the air but it had a lid which, if not closed properly, whistled. So the Stranraer became the ‘Whistling Shithouse’, modified to ‘Whistling Birdcage’ for more polite company. In a flush of enthusiasm, another six were ordered – but that was soon cancelled.

After the war started the Stranraer was used for coastal reconnaissance, mostly in the North Sea between Scotland and Norway but it was quickly replaced, largely by the Lockheed Hudson.

There is no record of any serious action against the enemy although an unusual photograph has emerged, taken from a Heinkel 111, of a brief encounter with a Stranraer over the Shetland Islands.

Its RAF career may have been brief but when the Stranraer was introduced it attracted attention in Canada. With extensive coastlines in East and West, coastal reconnaissance was a high priority for the RCAF. They took out a licence for the Stranraer to be built by Canadian Vickers and 40 were produced. They were used in frontline service until 1941 when they began to be replaced by the Catalina.

It is at this point that our story suffers from thread drift when we take up the tale of one of Stranraer’s pilots – Hughie Green. Hughie’s father was a Scot who had made his money in Canada selling tinned fish to the Army. He returned to London were Hughie was born in 1920. He was obsessed by the stage and his father encouraged him by inviting show-biz personalities to his home. Hughie was soon performing in local concerts and was noticed by a BBC producer and Hughie’s first national performance, aged 13, was three minutes on a radio programme, ‘In Town Tonight’. Brief performances in minor films helped his career. Meanwhile, he pursued an interest in aviation and learned to fly at Doncaster in 1939, just before the outbreak of war. He immediately volunteered for the RAF – they rejected him. His father had a trip planned to Canada and Hughie went with him where he was accepted by the RCAF. By 1941 he was a Sergeant instructor on Tiger Moths and the Link trainer. Alongside his service, he kept his show business career going, even managing to get special leave to appear on a show on Broadway. It had a short run. It opened the day before Pearl Harbor. Hughie went back to flying.

To escape from the routine and terror of basic instruction (many of his pupils were French-Canadian who could not, or would not, speak English) he engineered a transfer to a twin-engined course and learned to fly Ansons. At the end of the course, in May 1943, his posting was to 117 Squadron who were flying Catalinas on the east coast. First, he needed to learn to fly and sail a flying boat. He was sent to Patricia Bay on the west coast of Canada.

As a prospective Catalina pilot he was surprised to be introduced to a tall biplane – a Stranraer, still in useful second-line service. His instructor said ‘We could play tunes on its wires – or fly it’. They flew it and it proved to be a very effective trainer. He learned air and water handling, take-offs and 'landings' by day and by night. Surprisingly, when he joined his squadron and was converted to the Catalina he found that, whilst the Cat was a much more capable aeroplane the water handling of the Stranraer was definitely superior.

At the end of 1943, 17 Sqn were to be moved to Ceylon. Hughie and his friend learned that RAF Ferry Command needed two Catalina pilots. They asked to go and Hughie spent the rest of the war ferrying flying boats and many other types of aircraft around the world.

It was in the summer of 1944 that he had his first meeting with the Russians. President Roosevelt had agreed to sell 60 Catalinas to the Russians, reputedly for $3 per Cat, and a group of Russians had been ‘trained’ by the US Navy. They gladly opted to hand them over to the RAF Ferry Command to help them take the Cats home. Each team of six were given an RAF pilot as overseer plus a Wireless Operator. A Ukrainian translator had prepared a card with a list of useful phrases. The Russians had been given a schedule from Moscow and tried to stick to it rigidly – intending to fly across a cloudy Atlantic in tight formation, leaving for Iceland NOW (at 3.00 am in dense freezing fog) and so on. Hughie regards the six flights he did with them as his most dangerous moments of the war.

After the war he went back to show business but kept on flying. He was seen in a wide variety of aircraft types and was involved in selling aircraft - reputedly including surplus US Skyraiders to the French Navy. On the credit side, he was active in promoting flying opportunities for the Air Cadets, persuading Billy Butlin to buy a Beagle Husky and present it to the Cadets to be operated by the Air Experience Flight at Cambridge.

Anglia Television made a documentary about RAF Coltishall in 1959 and Hughie was the presenter. You can see it here: http://www.eafa.org.uk/catalogue/209623. The dialogue is a bit wooden but it’s interesting for the people included in the film, Johnnie Johnson, Bader, Stanford Tuck, Colin Hodgkinson etc.

In 1963 Hughie met the Russians again. He was flying from Stuttgart to Berlin Gatow in his Cessna 310 cruising at 200 mph at 9,500 ft. Berlin radar had just warned him of another aircraft approaching fast from his 5 o’ clock when a Mig flew past. After a second pass the Mig lowered its flaps and u/c and made signs for the Cessna to land. They were ignored.

The Mig opened fire, although not aiming to hit the Cessna and a Yak-25 joined in, flying past at near supersonic speeds causing the Cessna to roll violently, almost inverted. The left engine stopped. After more similar passes Hughie thought he had better give in and turned the Cessna to the right. The radar then told him he was only 27 miles from Berlin so he turned back on course and dived to gain speed. A little cloud cover helped him to get safely to Gatow. He flew home by Viscount. Although he couldn’t get clearance from the Russians for the Cessna to leave Berlin he waited for some weeks till the heat died down and left very early one morning using the shorter corridor to Hanover.

He did, of course, visit the RAF Museum and was convinced that the Stranraer there is the very one on which he trained (it isn’t). The Canadian Stranraers were used by the RCAF until 1946 when several were bought by local airlines up and down the west coast. CF-BXO was fitted with Wright engines and modified with a larger entrance door and other fittings for passengers but in the museum it wears the markings of 5 (Bomber Reconnaissance) Squadron.

To escape from the routine and terror of basic instruction (many of his pupils were French-Canadian who could not, or would not, speak English) he engineered a transfer to a twin-engined course and learned to fly Ansons. At the end of the course, in May 1943, his posting was to 117 Squadron who were flying Catalinas on the east coast. First, he needed to learn to fly and sail a flying boat. He was sent to Patricia Bay on the west coast of Canada.

As a prospective Catalina pilot he was surprised to be introduced to a tall biplane – a Stranraer, still in useful second-line service. His instructor said ‘We could play tunes on its wires – or fly it’. They flew it and it proved to be a very effective trainer. He learned air and water handling, take-offs and 'landings' by day and by night. Surprisingly, when he joined his squadron and was converted to the Catalina he found that, whilst the Cat was a much more capable aeroplane the water handling of the Stranraer was definitely superior.

At the end of 1943, 17 Sqn were to be moved to Ceylon. Hughie and his friend learned that RAF Ferry Command needed two Catalina pilots. They asked to go and Hughie spent the rest of the war ferrying flying boats and many other types of aircraft around the world.

It was in the summer of 1944 that he had his first meeting with the Russians. President Roosevelt had agreed to sell 60 Catalinas to the Russians, reputedly for $3 per Cat, and a group of Russians had been ‘trained’ by the US Navy. They gladly opted to hand them over to the RAF Ferry Command to help them take the Cats home. Each team of six were given an RAF pilot as overseer plus a Wireless Operator. A Ukrainian translator had prepared a card with a list of useful phrases. The Russians had been given a schedule from Moscow and tried to stick to it rigidly – intending to fly across a cloudy Atlantic in tight formation, leaving for Iceland NOW (at 3.00 am in dense freezing fog) and so on. Hughie regards the six flights he did with them as his most dangerous moments of the war.

After the war he went back to show business but kept on flying. He was seen in a wide variety of aircraft types and was involved in selling aircraft - reputedly including surplus US Skyraiders to the French Navy. On the credit side, he was active in promoting flying opportunities for the Air Cadets, persuading Billy Butlin to buy a Beagle Husky and present it to the Cadets to be operated by the Air Experience Flight at Cambridge.

Anglia Television made a documentary about RAF Coltishall in 1959 and Hughie was the presenter. You can see it here: http://www.eafa.org.uk/catalogue/209623. The dialogue is a bit wooden but it’s interesting for the people included in the film, Johnnie Johnson, Bader, Stanford Tuck, Colin Hodgkinson etc.

In 1963 Hughie met the Russians again. He was flying from Stuttgart to Berlin Gatow in his Cessna 310 cruising at 200 mph at 9,500 ft. Berlin radar had just warned him of another aircraft approaching fast from his 5 o’ clock when a Mig flew past. After a second pass the Mig lowered its flaps and u/c and made signs for the Cessna to land. They were ignored.

The Mig opened fire, although not aiming to hit the Cessna and a Yak-25 joined in, flying past at near supersonic speeds causing the Cessna to roll violently, almost inverted. The left engine stopped. After more similar passes Hughie thought he had better give in and turned the Cessna to the right. The radar then told him he was only 27 miles from Berlin so he turned back on course and dived to gain speed. A little cloud cover helped him to get safely to Gatow. He flew home by Viscount. Although he couldn’t get clearance from the Russians for the Cessna to leave Berlin he waited for some weeks till the heat died down and left very early one morning using the shorter corridor to Hanover.

He did, of course, visit the RAF Museum and was convinced that the Stranraer there is the very one on which he trained (it isn’t). The Canadian Stranraers were used by the RCAF until 1946 when several were bought by local airlines up and down the west coast. CF-BXO was fitted with Wright engines and modified with a larger entrance door and other fittings for passengers but in the museum it wears the markings of 5 (Bomber Reconnaissance) Squadron.