Charlie Taylor and the Wright Brothers (June 2021)

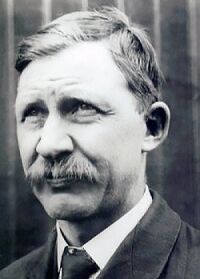

Ask anyone with the slightest interest in aviation – or in pub quizzing – who was the first to fly and they’ll tell you it was the Wright brothers. That brings out the pedant in real enthusiasts who will recall the thousands of flights of Otto Lilienthal. Then there was Percy Pilcher, his sister Ella, her cousin Dorothy and even Sir George Cayley’s coachman. Yes, but . . . and it’s a significant but. The Wrights designed, built and flew the world’s first aeroplane that was properly controllable and powered by an engine. Except that - they didn’t actually build that all important power unit. That was Charlie Taylor. The man in the background of this historic event who has been almost forgotten.

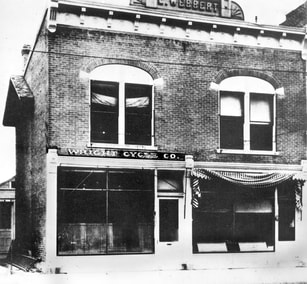

One sultry summer evening in 1901 they told him they really needed some help in the shop. Would he like a job? They offered him a higher rate of pay than Dayton Electric and, because the shop was near his home, he could cycle home every day for lunch with his family. The downside was the hours of work. 10 hours a day, six days a week. Charlie liked the Wrights and happily took the job.

He knew the brothers were interested in kites and had built several and also other oddly-shaped models. After extensive research into flying and other’s experiments they became convinced that building an inherently stable machine was entirely wrong. It had to be controllable. And jumping off hills was out, too. They wanted to launch into a steady wind and from the list of suggestions offered by the Weather Bureau they chose Kittyhawk, in North Carolina, a mere 675 miles from Dayton. That was really why they needed reliable help in the shop.

He knew the brothers were interested in kites and had built several and also other oddly-shaped models. After extensive research into flying and other’s experiments they became convinced that building an inherently stable machine was entirely wrong. It had to be controllable. And jumping off hills was out, too. They wanted to launch into a steady wind and from the list of suggestions offered by the Weather Bureau they chose Kittyhawk, in North Carolina, a mere 675 miles from Dayton. That was really why they needed reliable help in the shop.

Charlie enjoyed minding the shop when the brothers were away and did it well. In the boys’ absence, he was under the scrutiny of their sister, Katharine. She didn’t like Charlie at all. She thought he was too rough and ready, too familiar and disrespectful and, as well as being a non-Brethren, was definitely of the wrong class. She particularly hated his constant cigar smoking. But Wilbur and Orville liked Charlie and greatly valued his work and contribution to the development of the Flyer, so he stayed.

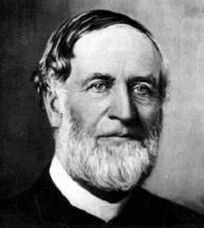

The brothers had carried out extensive and exhaustive research, starting in 1895 with a magazine called The Aeronautical Annual which led them to the little that had been published of the work of Sir George Cayley, Sir Hiram Maxim, Otto Lilienthal, Alexander Graham Bell and Percy Pilcher (who had actually built a powered machine but had tragically been killed before he could test it). There were others currently experimenting in America although the whole fantasy of aeronautics had been ridiculed by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The Wrights wrote copious letters to everyone who might have any practical experience or theoretical knowledge of the subject and dismissed much of what they learned as impractical, unproven or just wrong.

The brothers worked in the room above the shop, making wing ribs and other parts for the gliders which they would assemble at Kittyhawk. When they had came home after their first flights in 1900 they wanted to test different rib shapes to build the most efficient wing. Charlie had installed a gas engine in the workshop to power a lathe and they used this to drive the simple fan blades of a wind tunnel. Charlie helped by grinding down hacksaw blades and using them with bicycle spokes to make the balances which would hold and adjust the ribs being tested.

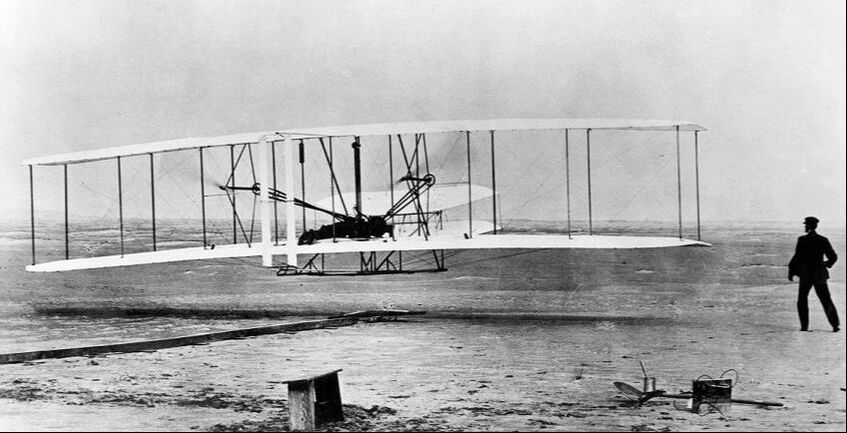

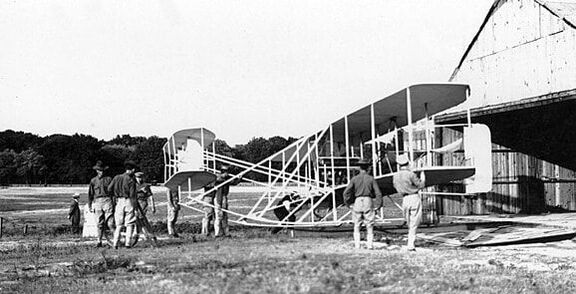

The photograph is of the replica

in Shuttleworth’s hangars.

The brothers worked in the room above the shop, making wing ribs and other parts for the gliders which they would assemble at Kittyhawk. When they had came home after their first flights in 1900 they wanted to test different rib shapes to build the most efficient wing. Charlie had installed a gas engine in the workshop to power a lathe and they used this to drive the simple fan blades of a wind tunnel. Charlie helped by grinding down hacksaw blades and using them with bicycle spokes to make the balances which would hold and adjust the ribs being tested.

The photograph is of the replica

in Shuttleworth’s hangars.

By opting to fly at Kittyhawk, the Wrights had burdened themselves with an enormous amount of extra work. The new glider had a span of 22 feet and was carefully broken down and packed along with a large tent and camping equipment. Most of the journey was by rail but then a boat had to be hired (Kittyhawk was on a long spit of land, largely uninhabited, which touched the mainland only at widely separated points). Sufficient lumber had to be purchased to make the shed intended to hangar the glider. The boat they needed was not small.

In July 1902 they landed in pouring rain which went on for two days after which they worked in swarms of mosquitoes and sand flies. Conditions were so bad that they almost abandoned the camp. Happily, the wind sprung up and the insects disappeared. The supply of fresh water was so far away that they interrupted the hangar building to dug a well. Though they were isolated in a desert they maintained a proper standard of living, bathing and changing their clothes regularly – they even had a supply of celluloid collars so that they were always properly dressed.

The brothers had corresponded regularly with Octave Chanute (born in France but American from the age of six). Chanute was an engineer approaching retirement and had become fascinated with flying. He had built and tested gliders. He studied the work of other experimenters, wrote a book and was making himself a self-appointed Professor of Aviation. He had persuaded the Wrights to have two of his protégés join them at the camp. They agreed reluctantly since they wanted to keep their work secret and patent what they could but the visitors proved to be very useful in the frequent manhandling of the glider.

In July 1902 they landed in pouring rain which went on for two days after which they worked in swarms of mosquitoes and sand flies. Conditions were so bad that they almost abandoned the camp. Happily, the wind sprung up and the insects disappeared. The supply of fresh water was so far away that they interrupted the hangar building to dug a well. Though they were isolated in a desert they maintained a proper standard of living, bathing and changing their clothes regularly – they even had a supply of celluloid collars so that they were always properly dressed.

The brothers had corresponded regularly with Octave Chanute (born in France but American from the age of six). Chanute was an engineer approaching retirement and had become fascinated with flying. He had built and tested gliders. He studied the work of other experimenters, wrote a book and was making himself a self-appointed Professor of Aviation. He had persuaded the Wrights to have two of his protégés join them at the camp. They agreed reluctantly since they wanted to keep their work secret and patent what they could but the visitors proved to be very useful in the frequent manhandling of the glider.

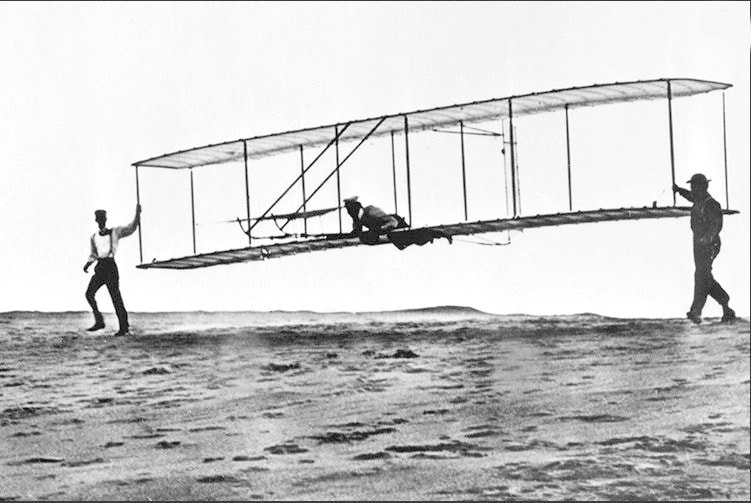

Eventually they began flying. With Wilbur or Orville lying on the lower wing the glider was lifted and pushed into the facing wind. Seconds later, it was down on the sand a few yards away. It had to be carried back to the top of the dune and made ready for the next launch. Launch after launch with the flight time accumulating in seconds. The longest flight was 12.5 seconds, some as short as 3. They experienced a stall for the first time – and after some discussion about Centre of Pressure(1) movement they reduced the curvature of the wing. They tested the wing warping and discovered adverse yaw(2). These things were entirely new to experimenters of flight. After two and a half months of repeatedly launching and repairing their glider when the wind was right and studying the birds when it wasn’t Wilbur and Orville put the glider in its shed and came home, deeply depressed. Their goal of controlled flight seemed to be more distant than ever.

On a second visit to Kittyhawk later in the year they tested Orville’s idea to fix the adverse yaw problem. They made the fixed rudder movable and linked it to the warp control. So when the wing was warped to the left, the rudder produced a yaw to the left, cancelling the adverse yaw. Brilliant.

The brothers reviewed the results of all their experiments and calculations before drawing up a provisional specification of their new glider. In the process they decided to leap to the next step. Their new machine would be fitted with an engine. It would have to be much larger to carry the extra weight of the engine and would have redesigned control surfaces. They calculated that the engine should weigh no more than 180lbs and produce at least 8 hp. It would drive two propellers via long chains and need to run smoothly so as not to put undue strain on the chains. The engines being made by motor manufacturers at the time were fairly primitive and all were larger and heavier than the Wright’s requirements. Nevertheless they sent letters to all twelve engine makers in the hope of getting a professionally built engine. No-one was interested.

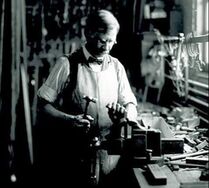

They decided to build it themselves. Well, the brothers were good craftsmen but had little experience of metalwork to the standard needed to build the engine. So they roughed out a plan with sketches rather than working drawings and handed them to Charlie. Whilst he studied and refined the design Orville built a larger wind tunnel and Wilbur worked on the plans for the new Flyer. All changes and modifications needed much discussion.

Both the boys were rather short tempered and Charlie was amused to overhear their ‘discussions’ – shouting loudly at each other – but noticeably never with any swearing. After one late night argument they came separately to Charlie next morning and each explained that they had been reflecting on their differences and had decided that the other had been right after all. When they met, they were soon shouting again, now putting the opposite case.

- As weight acts through the Centre of Gravity, lift acts through the Centre of Pressure. This can move forwards or backwards as the angle of attack (the angle at which the wing meets the airflow) changes. If the CP moves too far forward, the airflow over the wing breaks down and the wing stalls.

- To roll to the left, Wilbur warped the wing so that the angle of attack on the right wing increased, producing more lift to raise the right wing. But this also produced more drag, which slowed the wing, producing less lift. So the glider didn’t roll, it yawed to the right – adverse yaw.

On a second visit to Kittyhawk later in the year they tested Orville’s idea to fix the adverse yaw problem. They made the fixed rudder movable and linked it to the warp control. So when the wing was warped to the left, the rudder produced a yaw to the left, cancelling the adverse yaw. Brilliant.

The brothers reviewed the results of all their experiments and calculations before drawing up a provisional specification of their new glider. In the process they decided to leap to the next step. Their new machine would be fitted with an engine. It would have to be much larger to carry the extra weight of the engine and would have redesigned control surfaces. They calculated that the engine should weigh no more than 180lbs and produce at least 8 hp. It would drive two propellers via long chains and need to run smoothly so as not to put undue strain on the chains. The engines being made by motor manufacturers at the time were fairly primitive and all were larger and heavier than the Wright’s requirements. Nevertheless they sent letters to all twelve engine makers in the hope of getting a professionally built engine. No-one was interested.

They decided to build it themselves. Well, the brothers were good craftsmen but had little experience of metalwork to the standard needed to build the engine. So they roughed out a plan with sketches rather than working drawings and handed them to Charlie. Whilst he studied and refined the design Orville built a larger wind tunnel and Wilbur worked on the plans for the new Flyer. All changes and modifications needed much discussion.

Both the boys were rather short tempered and Charlie was amused to overhear their ‘discussions’ – shouting loudly at each other – but noticeably never with any swearing. After one late night argument they came separately to Charlie next morning and each explained that they had been reflecting on their differences and had decided that the other had been right after all. When they met, they were soon shouting again, now putting the opposite case.

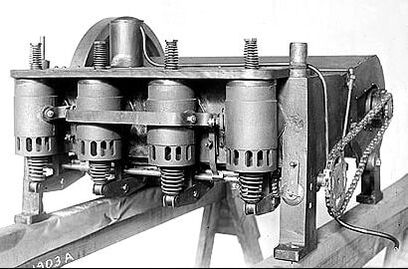

Charlie studied the engine sketches, four water-cooled inline cylinders, lying horizontally. He had the castings produced by a local foundry. The engine block was aluminium alloy (with 8% copper), the other castings were iron. He got to work with the lathe, a file and occasionally even a hammer and chisel. The crankshaft was carved out of a slab of steel and Charlie was proud that it balanced perfectly.

There was no fuel pump or carburettor. Petrol was dripped in through this air intake where it vaporised on the hot crankcase and was drawn into the cylinders. Sparking plugs were absent, just two contact points in each cylinder which arced and sparked when a coil produced a timely current. And – no throttle. The engine would run at one speed.

It was February 1903 when the engine was ready for testing. It worked, but only briefly. The cooling water wasn’t circulated, just topped up as it evaporated. The valves became red hot and the engine was quickly shut down. Next day, the bearings seized and the crankcase shattered. A new casting was ordered.

It arrived in April and Charlie performed his magic on it, also modifying the cooling system. And this time they were rewarded by little engine running perfectly, filling the workshop with happy noise and cheerful blue smoke.

It was February 1903 when the engine was ready for testing. It worked, but only briefly. The cooling water wasn’t circulated, just topped up as it evaporated. The valves became red hot and the engine was quickly shut down. Next day, the bearings seized and the crankcase shattered. A new casting was ordered.

It arrived in April and Charlie performed his magic on it, also modifying the cooling system. And this time they were rewarded by little engine running perfectly, filling the workshop with happy noise and cheerful blue smoke.

They were even more delighted to find that it was producing much more than the 8hp they had aimed for. They measured 12hp. That extra power, and the fact that the engine weighed only 150 lbs allowed the brothers to strengthen the structure of the Flyer.

Now that they had an engine, the brothers turned their attention to the propellers. They didn’t anticipate any problems, the marine industry had changed to using propellers because they were much more efficient than paddle wheels.

They were astonished to find no scientific study on the design of propellers. Each builder simply made something that looked right. They all worked but no-one seemed to care how efficient they were. (Later studies showed that few were better than 50% efficient).

Now that they had an engine, the brothers turned their attention to the propellers. They didn’t anticipate any problems, the marine industry had changed to using propellers because they were much more efficient than paddle wheels.

They were astonished to find no scientific study on the design of propellers. Each builder simply made something that looked right. They all worked but no-one seemed to care how efficient they were. (Later studies showed that few were better than 50% efficient).

So the Wrights started from scratch. Because their propellers would be working in air they decided, after many of their prolonged ‘discussions’, they would consider them to be rotating wings travelling in a spiral. They filled five notebooks with technical data from wind tunnel tests and calculations. A review of this work by modern aeronautical engineers concluded that it ‘revealed a degree of technical sophistication in applied aerodynamics never seen before. Their application of the theory in designing a real propeller was masterful’. In its own right it should have earned an international scientific award. In the event it was overshadowed by their more spectacular achievement, the first powered flight.

The propellers were made of three laminations of spruce 8½ feet long to be driven by chains from the flywheel. The engine was mounted on the lower wing beside the pilot – ‘so that it wouldn’t fall on him in a crash’. One of the chains was twisted so that this very first aeroplane had the sophistication of contra-rotating propellers.

Various distractions delayed the planned trip to Kill Devil Hills and the crates containing the Flyer, its engine and all the other equipment didn’t leave until late September. The brothers preceded it by passenger train. When they got to Kittyhawk they found that storms had lifted the old shed off its foundations and blown it some distance across the sand. Fortunately the glider inside was little damaged and soon they were practising their piloting skills and even soaring in front of the dunes. One flight lasted over a minute.

They built a larger shed for the Flyer which finally arrived in early October. Almost immediately it began to rain, the first of a storm which was to last four days with winds gusting at 75 mph. The building shook and tarpaper was ripped off the roofs but nothing inside was damaged. Next they assembled the 60 ft long metal capped launching rail. It was not until 5th November that the Flyer was rigged and ready for testing.

When the engine started it was misfiring badly. Vibrations jerked the chains and soon the tubular propeller shafts began to twist and buckle. They couldn’t be repaired at Kittyhawk so had to be sent back to Dayton for Charlie to make new shafts.

They shafts came back on 20th November. Wilbur and Orville couldn’t resist fitting them immediately. They started the motor. It ran erratically and shook the sprocket wheels loose. They tightened the nuts and tried again. Every time the sprocket wheels loosened. Soon they were using a six foot long piece of 4 X 2 to get maximum leverage on nut-tightening. They still rattled loose. Then Orville remembered they had brought some Arnstein’s hard cement which they normally used to lock bicycle tyres on wheel rims. It worked. The nuts stayed locked on the sprockets.

Next morning they tested the engine power. The Flyer was placed on its launching rail with a rope running over a pulley to spring balance scales on a heavy box of sand. The Flyer had grown to 700 lbs weight and Wilbur calculated that the engine would have to produce at least 100 lbs of static thrust. They ran up the engine until the flailing propellers began to inch the Flyer forward, raising the box of sand. All the readings were checked and notebooks consulted. The propellers had been turning at 351 rpm and Charlie’s engine had delivered a thrust of 132 lbs.

At this point, naturally, the weather turned. Driving rain, sleet, snow, gale force winds. The brothers sheltered in the hangar with the Flyer. They suspended it from its wings with one of them aboard and full fuel then ran the engine to check for vibration and any sign of structural weakness. There was none. They attached instruments to the Flyer. An anemometer to measure the air speed, a rev. counter and a stopwatch, all three connected by string and levers so that they could be started and stopped simultaneously. It was while testing this system that they were horrified to see that the propeller shafts were beginning to twist again.

It was the 28th of November. Time was running out. It was imperative that all the family had to be together at home for their traditional Christmas. The brothers decided there was just time to make a final effort. Orville would go home and supervise the making of new shafts, this time of solid rather than tubular steel.

It took two days for him to find a boat – whilst the weather immediately brightened. He got home on 3rd December. Charlie made the new shafts and Orville was back from his 1500 mile round trip installing them on the Flyer on 12th December. The brothers lifted it onto its launching rail. There was no wind so they could test only that it rolled smoothly along the track.

The next day, the weather was perfect and the wind just right. But it was Sunday. The Bishop’s sons would not break the Sabbath. They read books and strolled along the beach.

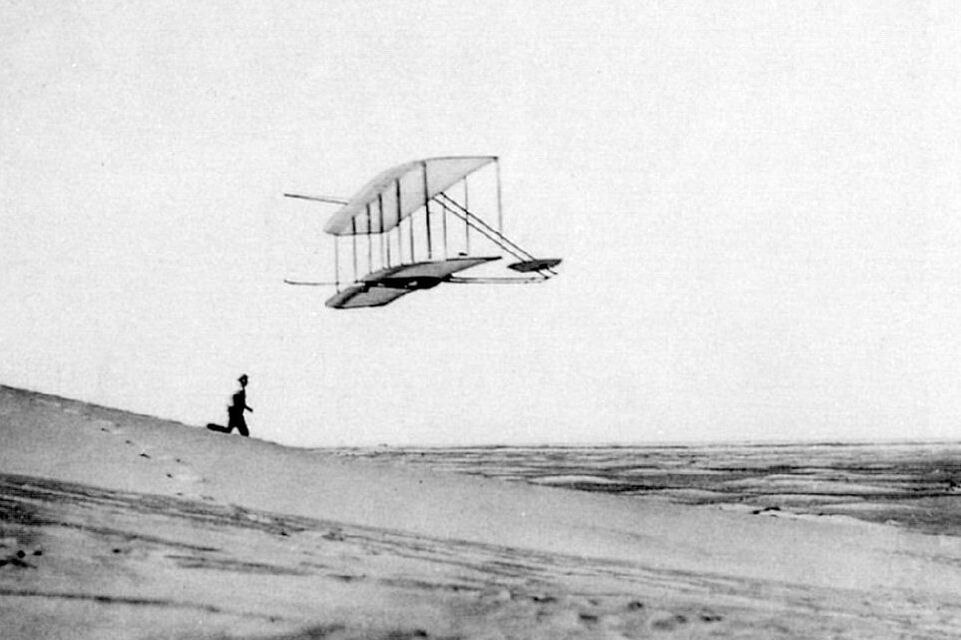

Monday’s wind was not strong enough to attempt a level launch so, with the help of five men, two boys and a dog from the nearby lifesaving station they dragged the heavy Flyer and its launching rail a quarter of a mile to the slopes of a large dune. A downhill start would give them flying speed. They tossed a coin and Wilbur won. Both the brothers held a propeller and swung it. The engine burst into life and Wilbur climbed onto the hip cradle on the lower wing. On release, the Flyer left the track after only 40 feet, pitched up into a climb, stalled and settled onto the sand. It had ‘flown’ just 60 feet. The Flyer was carried back to its hangar and the brothers repaired the damage to the front elevator. Wilbur had found this to be very sensitive and over powerful. There wasn’t time to change the hinge point and Orville determined to handle it carefully when it was his turn to fly.

It was Wednesday afternoon before the Flyer was mounted on its launching rail again. There was no wind at all. The brothers knew the Flyer couldn’t reach flying speed by the end of the 60 ft rail and would certainly crash. It was put back in its hangar for the night.

The following freezing morning the wind was rattling their building as they went through the routine of washing and dressing, choosing a clean stiff collar and knotting their ties carefully. Their hand held anemometer found the wind gusting between 22 and 27 mph. They waited for it to die down. It didn’t and at 10 o’ clock they hung out a red flag which was a signal for the five men from the life-saving station to come and help. At 10.35am (on Thursday 17th December 1903) Orville shouted that he was ready to go, Wilbur ran with a wingtip for the first 40 feet when the Flyer lifted into the air and John Daniels squeezed the bulb of Wilbur’s camera to take this famous photograph.

The propellers were made of three laminations of spruce 8½ feet long to be driven by chains from the flywheel. The engine was mounted on the lower wing beside the pilot – ‘so that it wouldn’t fall on him in a crash’. One of the chains was twisted so that this very first aeroplane had the sophistication of contra-rotating propellers.

Various distractions delayed the planned trip to Kill Devil Hills and the crates containing the Flyer, its engine and all the other equipment didn’t leave until late September. The brothers preceded it by passenger train. When they got to Kittyhawk they found that storms had lifted the old shed off its foundations and blown it some distance across the sand. Fortunately the glider inside was little damaged and soon they were practising their piloting skills and even soaring in front of the dunes. One flight lasted over a minute.

They built a larger shed for the Flyer which finally arrived in early October. Almost immediately it began to rain, the first of a storm which was to last four days with winds gusting at 75 mph. The building shook and tarpaper was ripped off the roofs but nothing inside was damaged. Next they assembled the 60 ft long metal capped launching rail. It was not until 5th November that the Flyer was rigged and ready for testing.

When the engine started it was misfiring badly. Vibrations jerked the chains and soon the tubular propeller shafts began to twist and buckle. They couldn’t be repaired at Kittyhawk so had to be sent back to Dayton for Charlie to make new shafts.

They shafts came back on 20th November. Wilbur and Orville couldn’t resist fitting them immediately. They started the motor. It ran erratically and shook the sprocket wheels loose. They tightened the nuts and tried again. Every time the sprocket wheels loosened. Soon they were using a six foot long piece of 4 X 2 to get maximum leverage on nut-tightening. They still rattled loose. Then Orville remembered they had brought some Arnstein’s hard cement which they normally used to lock bicycle tyres on wheel rims. It worked. The nuts stayed locked on the sprockets.

Next morning they tested the engine power. The Flyer was placed on its launching rail with a rope running over a pulley to spring balance scales on a heavy box of sand. The Flyer had grown to 700 lbs weight and Wilbur calculated that the engine would have to produce at least 100 lbs of static thrust. They ran up the engine until the flailing propellers began to inch the Flyer forward, raising the box of sand. All the readings were checked and notebooks consulted. The propellers had been turning at 351 rpm and Charlie’s engine had delivered a thrust of 132 lbs.

At this point, naturally, the weather turned. Driving rain, sleet, snow, gale force winds. The brothers sheltered in the hangar with the Flyer. They suspended it from its wings with one of them aboard and full fuel then ran the engine to check for vibration and any sign of structural weakness. There was none. They attached instruments to the Flyer. An anemometer to measure the air speed, a rev. counter and a stopwatch, all three connected by string and levers so that they could be started and stopped simultaneously. It was while testing this system that they were horrified to see that the propeller shafts were beginning to twist again.

It was the 28th of November. Time was running out. It was imperative that all the family had to be together at home for their traditional Christmas. The brothers decided there was just time to make a final effort. Orville would go home and supervise the making of new shafts, this time of solid rather than tubular steel.

It took two days for him to find a boat – whilst the weather immediately brightened. He got home on 3rd December. Charlie made the new shafts and Orville was back from his 1500 mile round trip installing them on the Flyer on 12th December. The brothers lifted it onto its launching rail. There was no wind so they could test only that it rolled smoothly along the track.

The next day, the weather was perfect and the wind just right. But it was Sunday. The Bishop’s sons would not break the Sabbath. They read books and strolled along the beach.

Monday’s wind was not strong enough to attempt a level launch so, with the help of five men, two boys and a dog from the nearby lifesaving station they dragged the heavy Flyer and its launching rail a quarter of a mile to the slopes of a large dune. A downhill start would give them flying speed. They tossed a coin and Wilbur won. Both the brothers held a propeller and swung it. The engine burst into life and Wilbur climbed onto the hip cradle on the lower wing. On release, the Flyer left the track after only 40 feet, pitched up into a climb, stalled and settled onto the sand. It had ‘flown’ just 60 feet. The Flyer was carried back to its hangar and the brothers repaired the damage to the front elevator. Wilbur had found this to be very sensitive and over powerful. There wasn’t time to change the hinge point and Orville determined to handle it carefully when it was his turn to fly.

It was Wednesday afternoon before the Flyer was mounted on its launching rail again. There was no wind at all. The brothers knew the Flyer couldn’t reach flying speed by the end of the 60 ft rail and would certainly crash. It was put back in its hangar for the night.

The following freezing morning the wind was rattling their building as they went through the routine of washing and dressing, choosing a clean stiff collar and knotting their ties carefully. Their hand held anemometer found the wind gusting between 22 and 27 mph. They waited for it to die down. It didn’t and at 10 o’ clock they hung out a red flag which was a signal for the five men from the life-saving station to come and help. At 10.35am (on Thursday 17th December 1903) Orville shouted that he was ready to go, Wilbur ran with a wingtip for the first 40 feet when the Flyer lifted into the air and John Daniels squeezed the bulb of Wilbur’s camera to take this famous photograph.

Try as he might, Orville found the Flyer difficult to control and it swooped up and down before it lurched into the sand. He had been airborne for only 12 seconds but it was 12 seconds of real flight and the landing was at a point no lower than its take-off.

A minor repair was needed then it was Wilbur’s turn. He, too flew for 12 seconds. Orville’s second flight lasted for 15 seconds. At 12 noon, Wilbur launched again and achieved a smoother flight, going on until the inevitable twitch into the ground 852 feel from the launch point. This flight lasted 59 seconds, a clear demonstration of the Wright’s mastery of the air.

The Flyer was dragged back to the launching rail for another minor repair and Orville made a plan for his next flight hoping to cover the four miles to the village of Kittyhawk. Then a sudden gust caught a wingtip which rose high in the air. Three of them grabbed a strut but they couldn’t hold on and the Flyer rolled over into a heap of tangled wreckage. It was pulled into the hangar.

Wilbur and Orville walked to Kittyhawk to send a telegram to their father. They included the words ‘Inform press’. In Dayton, Katherine took the telegram, some notes giving brief details of the Flyer and a couple of pen portraits of the flying brothers. She gave them to another brother, Lorin, who knew the local newspaper editor. He said he’d take them round when he’d finished his dinner.

The editor was sceptical. The next morning, nothing appeared in the Dayton paper. But the news had been leaked out via one of the telegraph operators who told a journalist friend. Thus a North Carolina newspaper ran a fanciful story about ‘aerial navigation without a balloon’ embellished by entirely invented ‘facts’. The news trickled into other journals and for a time reporters arrived in Dayton in an effort to establish the true facts and how important this event was. Charlie Taylor never seems to have been mentioned.

In the spring of 1904, Wilbur and Orville began to build the Flyer II, the same size as the original but with many improvements and so faster and heavier. Charlie was now running the cycle business on his own although he made time to modify his engine to produce 16 hp.

The Wrights rented a field just 8 miles from Dayton where they could fly, provided they ‘shoo-ed the cows out of the way first’. It was a hummocky field half a mile long and a quarter of a mile wide. It was not a good flying ground. The inland weather pattern seldom gave a steady wind and the trees around the field made the flow turbulent. The altitude, 800 ft a.m.s.l. and the higher summer temperatures made the atmosphere less dense than at Kittyhawk so the wings produced less lift and the engine struggled. Anyone who came to ‘see the Wright boys fly’ was usually disappointed. There were many more failed take offs than flights. Reporters looking for a story soon lost interest and stayed away.

Early in September, the brothers had an idea. They built a sturdy tripod from which they hung a ¾ ton weight. It hung on a rope which ran round pulleys to a hook on the front of the launching trolley. When the rope was released the weight fell and the Flyer sped along the rail.

A minor repair was needed then it was Wilbur’s turn. He, too flew for 12 seconds. Orville’s second flight lasted for 15 seconds. At 12 noon, Wilbur launched again and achieved a smoother flight, going on until the inevitable twitch into the ground 852 feel from the launch point. This flight lasted 59 seconds, a clear demonstration of the Wright’s mastery of the air.

The Flyer was dragged back to the launching rail for another minor repair and Orville made a plan for his next flight hoping to cover the four miles to the village of Kittyhawk. Then a sudden gust caught a wingtip which rose high in the air. Three of them grabbed a strut but they couldn’t hold on and the Flyer rolled over into a heap of tangled wreckage. It was pulled into the hangar.

Wilbur and Orville walked to Kittyhawk to send a telegram to their father. They included the words ‘Inform press’. In Dayton, Katherine took the telegram, some notes giving brief details of the Flyer and a couple of pen portraits of the flying brothers. She gave them to another brother, Lorin, who knew the local newspaper editor. He said he’d take them round when he’d finished his dinner.

The editor was sceptical. The next morning, nothing appeared in the Dayton paper. But the news had been leaked out via one of the telegraph operators who told a journalist friend. Thus a North Carolina newspaper ran a fanciful story about ‘aerial navigation without a balloon’ embellished by entirely invented ‘facts’. The news trickled into other journals and for a time reporters arrived in Dayton in an effort to establish the true facts and how important this event was. Charlie Taylor never seems to have been mentioned.

In the spring of 1904, Wilbur and Orville began to build the Flyer II, the same size as the original but with many improvements and so faster and heavier. Charlie was now running the cycle business on his own although he made time to modify his engine to produce 16 hp.

The Wrights rented a field just 8 miles from Dayton where they could fly, provided they ‘shoo-ed the cows out of the way first’. It was a hummocky field half a mile long and a quarter of a mile wide. It was not a good flying ground. The inland weather pattern seldom gave a steady wind and the trees around the field made the flow turbulent. The altitude, 800 ft a.m.s.l. and the higher summer temperatures made the atmosphere less dense than at Kittyhawk so the wings produced less lift and the engine struggled. Anyone who came to ‘see the Wright boys fly’ was usually disappointed. There were many more failed take offs than flights. Reporters looking for a story soon lost interest and stayed away.

Early in September, the brothers had an idea. They built a sturdy tripod from which they hung a ¾ ton weight. It hung on a rope which ran round pulleys to a hook on the front of the launching trolley. When the rope was released the weight fell and the Flyer sped along the rail.

Now every launch was successful and flight times increased. By the end of September they were flying complete circles and their best flight time was 1 min 38 secs. Charlie was now so much involved whenever the brothers were flying, that he effectively became the airport manager, preparing the Flyer for launching helping with the frequent repairs and modifications and meticulously recording the flight times. Gradually, the cycle business was abandoned.

The popular press remained unmoved. However, word was spreading in more informed society and forward thinkers in the military and in business were showing interest. The Wrights remained fiercely protective of their secrets and patented everything they could but they realised they had to find a buyer. They still had not solved the problem of the over-sensitive elevator though in the process they invented that simple flying instrument, the piece of wool tied to something in the pilot’s view to show slip and skid that is still in use today on every glider and on many powered machines and was critical on the Harrier.

In June 1905, Flyer III emerged from the workshop, The forward elevator and rear rudders were moved further away from the wing which improved control response. With the effective launching equipment, flight times extended and soon exceeded an hour.

News of the Wrights success spread through the aviation interested community. Decision makers in the US Military were the greatest sceptics and it seemed they would never buy a machine. The Wrights had had contacts with the British, even a social visit by Lt. Col. Capper of the British Army’s Balloon Factory who was in America with his wife. (They made a good impression on each other but Capper wasn’t allowed to see the Flyer). From France came a representative of the French Aero Club. They couldn’t tolerate that the aeroplane wasn’t being developed in France and wanted to buy a Flyer to confirm which of the many conflicting reports they had heard was true.

The greatest stumbling block to any sale was the obsessive secrecy of the brothers themselves. They refused to demonstrate, or even show, the Flyer to a potential customer until the terms of sale had been agreed – and they were asking $200,000, a million Francs.

A long period of detailed negotiations ensued, mostly by correspondence. This was complicated by mis-delivery of letters to the wrong person in a department, a lack of understanding of details in the Wright’s letters and even of what a flying machine looked like or could do. Encouraged by a self-appointed negotiator, Hart O. Berg, an American living in France and with some experience as an arms dealer, Wilbur agreed to come to Europe. There was talk of deals with Germany as well as France and England and Wilbur was joined by Orville and Charlie who brought a Flyer they had built. This was parked in its crate in Le Havre docks.

The brothers were concerned that the unsophisticated Charlie might succumb to the dissolute Parisian life, have too much to drink and give away all their secrets. He was booked, incognito, into a small hotel round the corner from the brothers. He didn’t talk, even when he was left alone and seriously bored whilst Wilbur went to Berlin and Orville to visit Col. Capper at his home in England. They left for home with no sales or even a likely prospect. The only outcome of their visit was to clarify their relationship with Berg. He was to be, simply, their agent on commission.

On the way home in the last weeks of 1907 Wilbur learned that he had been invited to Washington to meet the Army’s Chief Signal Officer, Brig. Gen Allen. The army was not going to buy a Flyer but they were going to call for tenders for a military aeroplane which could carry a pilot and passenger at an average speed of 40 mph over a 10 mile flight. It should carry fuel for 125 miles and ‘permit an intelligent man to become proficient in its use within a reasonable time’.

The newspapers had a field day with the specification. They all declared it so fanciful that there would be no tender received. In the end, there were 41. Only the Wright’s, at $25,000 was serious.

The trials would be in late August 1908. The brothers had not flown for two and a half years and needed to practise. They rebuilt and updated the Flyer and took it to Kittyhawk hoping to avoid the press. They were tracked down by reporters and the usual round of fantastical stories appeared even though they completed only short flights. On the last flight, Wilbur mishandled the controls and the Flyer dived into the ground. Wilbur escaped with bruises. He was more concerned to hear from Hart O.Berg that a syndicate intending to sell Wright biplanes across Europe was in danger of breaking up – and a biplane built by Gabriel Voisin had just completed a 2½ mile flight. He had to go to France immediately to demonstrate the superiority of his machine. He went directly to New York and sailed on 21st May.

Wilbur was invited by a friendly car manufacturer to base himself at Le Mans, then a quiet town some way from Paris. He was offered him a workshop and the help of some mechanics. When the crate containing the Flyer was brought from Le Havres Wilbur was dismayed when he opened it. The Flyer was broken and the pieces scattered in a jumble. He wrote an angry letter to Orville and Charlie. It was weeks later that he learned that they had, of course, properly packed the Flyer. At Le Havre, it had been over-enthusiastically examined by the French customs officials.

In June 1905, Flyer III emerged from the workshop, The forward elevator and rear rudders were moved further away from the wing which improved control response. With the effective launching equipment, flight times extended and soon exceeded an hour.

News of the Wrights success spread through the aviation interested community. Decision makers in the US Military were the greatest sceptics and it seemed they would never buy a machine. The Wrights had had contacts with the British, even a social visit by Lt. Col. Capper of the British Army’s Balloon Factory who was in America with his wife. (They made a good impression on each other but Capper wasn’t allowed to see the Flyer). From France came a representative of the French Aero Club. They couldn’t tolerate that the aeroplane wasn’t being developed in France and wanted to buy a Flyer to confirm which of the many conflicting reports they had heard was true.

The greatest stumbling block to any sale was the obsessive secrecy of the brothers themselves. They refused to demonstrate, or even show, the Flyer to a potential customer until the terms of sale had been agreed – and they were asking $200,000, a million Francs.

A long period of detailed negotiations ensued, mostly by correspondence. This was complicated by mis-delivery of letters to the wrong person in a department, a lack of understanding of details in the Wright’s letters and even of what a flying machine looked like or could do. Encouraged by a self-appointed negotiator, Hart O. Berg, an American living in France and with some experience as an arms dealer, Wilbur agreed to come to Europe. There was talk of deals with Germany as well as France and England and Wilbur was joined by Orville and Charlie who brought a Flyer they had built. This was parked in its crate in Le Havre docks.

The brothers were concerned that the unsophisticated Charlie might succumb to the dissolute Parisian life, have too much to drink and give away all their secrets. He was booked, incognito, into a small hotel round the corner from the brothers. He didn’t talk, even when he was left alone and seriously bored whilst Wilbur went to Berlin and Orville to visit Col. Capper at his home in England. They left for home with no sales or even a likely prospect. The only outcome of their visit was to clarify their relationship with Berg. He was to be, simply, their agent on commission.

On the way home in the last weeks of 1907 Wilbur learned that he had been invited to Washington to meet the Army’s Chief Signal Officer, Brig. Gen Allen. The army was not going to buy a Flyer but they were going to call for tenders for a military aeroplane which could carry a pilot and passenger at an average speed of 40 mph over a 10 mile flight. It should carry fuel for 125 miles and ‘permit an intelligent man to become proficient in its use within a reasonable time’.

The newspapers had a field day with the specification. They all declared it so fanciful that there would be no tender received. In the end, there were 41. Only the Wright’s, at $25,000 was serious.

The trials would be in late August 1908. The brothers had not flown for two and a half years and needed to practise. They rebuilt and updated the Flyer and took it to Kittyhawk hoping to avoid the press. They were tracked down by reporters and the usual round of fantastical stories appeared even though they completed only short flights. On the last flight, Wilbur mishandled the controls and the Flyer dived into the ground. Wilbur escaped with bruises. He was more concerned to hear from Hart O.Berg that a syndicate intending to sell Wright biplanes across Europe was in danger of breaking up – and a biplane built by Gabriel Voisin had just completed a 2½ mile flight. He had to go to France immediately to demonstrate the superiority of his machine. He went directly to New York and sailed on 21st May.

Wilbur was invited by a friendly car manufacturer to base himself at Le Mans, then a quiet town some way from Paris. He was offered him a workshop and the help of some mechanics. When the crate containing the Flyer was brought from Le Havres Wilbur was dismayed when he opened it. The Flyer was broken and the pieces scattered in a jumble. He wrote an angry letter to Orville and Charlie. It was weeks later that he learned that they had, of course, properly packed the Flyer. At Le Havre, it had been over-enthusiastically examined by the French customs officials.

The lack of a single word of the other’s language meant that Wilbur and his team took seven weeks to repair and assemble the Flyer. It was taken to a nearby field and placed in a shed there. Wilbur moved in with it and camped in the shed as he had done at Kittyhawk.

On Saturday, 8th August the Flyer was pulled out onto its rail. A small crowd waited expectantly. Wilbur fussed with it for hours and some of the crowd drifted away. It wasn’t until in the evening that Wilbur started the engine and tripped the weight. The Flyer leapt into to sky and astonished the onlookers particularly by its steady banked turns. After two circuits of the field, Wilbur landed smoothly near his starting rail.

The flight had lasted just two minutes but it changed everything. Wilbur was hailed as a hero and was declared to have ‘a power which controls the fate of nations’. Bleriot called it the beginning of ‘a new era in mechanical flight’.

Wilbur wouldn’t fly the next day, it was Sunday. But on Monday he flew again, several times, cheered by thousands. As his fame spread he was invited to fly at other fields and soon was covering distances of 30 miles and flying for up to 40 minutes. People were travelling from England and even Russia to see him.

Back in America, Orville, too, was becoming famous. When he travelled to Washington to join Charlie and the Flyer for the army trials, he was plucked from his modest hotel and installed in the up market Cosmos Club. The shy Orville was overwhelmed by his reception. At Fort Myers he met the three Army lieutenants who had been selected to be trained to fly. One was Lt. Thomas Selfridge who had been working with a group formed by Alexander Graham Bell and had already flown their first aeroplane. He was clearly a rival although their machine was not yet capable of entering the competition.

Orville started badly. Charlie had to work on the engine – now much more sophisticated than the original – to get it running smoothly. The first circuit of the field was fine, then Orville mishandled the controls - as Wilbur had done in France – and the Flyer dived to a hard landing.

But Orville’s later flights confounded all the sceptics and soon he was setting records.

Charlie painted his flight times on the roof of the shed - 50, 55, drop the paintbrush - and cheer. Orville also flew unusually high. One day to 200ft, later even 300 ft.

On 17th September Orville promised he would take Charlie up for his first flight. He was already in the seat when a general asked Orville to fly Lt Selfridge. Orville couldn’t refuse – he was a member of the judging committee. Charlie gave up his seat. Selfridge was a big heavy man and the Flyer was not airborne when it got to the end of the rail. It skidded across the rough grass before staggering into the air. Nevertheless, Orville flew three smooth circuits to the usual accompaniment of cheering. Then he heard a tapping sound, followed by two thuds. Observers on the ground saw a propeller blade falling free.

Orville shut off the engine and tried to warp the Flyer away from some trees. It fell out of control and dived steeply crashing to the ground. The wings folded over the wreckage.

Orville shut off the engine and tried to warp the Flyer away from some trees. It fell out of control and dived steeply crashing to the ground. The wings folded over the wreckage.

Charlie was one of the first to reach the crash and helped to push up the wings to release the two men.

Selfridge lay still, blood pouring from his head. Orville, with blood on his face was moaning. Charlie took off his collar and loosened his tie. When the casualties were taken away on stretchers Charlie leaned against the wreckage and cried bitterly.

Octave Chanute had witnessed the crash and soon established the sequence of events. A propeller had split causing it to vibrate. It slipped off the shaft hitting one of the wires bracing the rear rudders. These had twisted to be nearly horizontal, pitching the Flyer into its fatal dive.

The army doctors worked on the victims and released the news that Lt Selfridge was dead. His skull had been fractured. Orville would recover although he had a scalp wound, fractured thigh, several broken ribs and an injury to his back. (It wasn’t until 12 years later when Orville had some X-rays that it was found that the army doctors missed the dislocated hip and three hip bone fractures).

In Dayton, Katherine immediately resigned from her job as a school teacher and came to Washington to care for Orville. Having to deal with the mountain of correspondence, messages and gifts she became Orville’s temporary secretary which soon became her permanent role. In France, Wilbur was deeply shocked by the news and somehow blamed himself. After a period of almost monastic isolation he threw himself back into his programme of demonstrations to a curiously unresponsive market. He set records, won prizes totalling several thousand dollars, and was given awards and medals. The syndicate that would market his aeroplanes was set up and Wilbur began instructing the first pupils. He met and became a friend of Charles Rolls, who arranged for the Short brothers to take out a licence to build Wright aeroplanes.

Then began a period of charge and counter-charge about the infringement of patents. The principal topic, but not the only one, was wing warping and, by extension the use of hinged flaps, or ailerons. Many of the battles went to court, which seldom proved to end the dispute. Wilbur would never give up a case and he went on fighting until his early death in 1912 at the age of 45.

In 1910 the Wrights opened a factory. In one corner was the engine shop which was to be run by Charlie. The factory was intended to produce two aircraft per month but was more in character with cottage industry rather than a production line. The brothers were no businessmen and kept away from day to day management. Whilst other aeroplanes were being fitted with wheeled undercarriages the Wrights stuck to a launching rail and a weight on a wooden tower. There was no standard layout of controls. There were still two sticks, both moving fore and aft. Rudder control was sometimes a small lever hinged to the top of one of the sticks; a foot pedal could be the throttle. They had to update the design. When it emerged, as the Wright B, it had wheels and the sensitive forward elevator was gone, banished to the tail. With a 35 hp engine it flew at 45 mph.

The army doctors worked on the victims and released the news that Lt Selfridge was dead. His skull had been fractured. Orville would recover although he had a scalp wound, fractured thigh, several broken ribs and an injury to his back. (It wasn’t until 12 years later when Orville had some X-rays that it was found that the army doctors missed the dislocated hip and three hip bone fractures).

In Dayton, Katherine immediately resigned from her job as a school teacher and came to Washington to care for Orville. Having to deal with the mountain of correspondence, messages and gifts she became Orville’s temporary secretary which soon became her permanent role. In France, Wilbur was deeply shocked by the news and somehow blamed himself. After a period of almost monastic isolation he threw himself back into his programme of demonstrations to a curiously unresponsive market. He set records, won prizes totalling several thousand dollars, and was given awards and medals. The syndicate that would market his aeroplanes was set up and Wilbur began instructing the first pupils. He met and became a friend of Charles Rolls, who arranged for the Short brothers to take out a licence to build Wright aeroplanes.

Then began a period of charge and counter-charge about the infringement of patents. The principal topic, but not the only one, was wing warping and, by extension the use of hinged flaps, or ailerons. Many of the battles went to court, which seldom proved to end the dispute. Wilbur would never give up a case and he went on fighting until his early death in 1912 at the age of 45.

In 1910 the Wrights opened a factory. In one corner was the engine shop which was to be run by Charlie. The factory was intended to produce two aircraft per month but was more in character with cottage industry rather than a production line. The brothers were no businessmen and kept away from day to day management. Whilst other aeroplanes were being fitted with wheeled undercarriages the Wrights stuck to a launching rail and a weight on a wooden tower. There was no standard layout of controls. There were still two sticks, both moving fore and aft. Rudder control was sometimes a small lever hinged to the top of one of the sticks; a foot pedal could be the throttle. They had to update the design. When it emerged, as the Wright B, it had wheels and the sensitive forward elevator was gone, banished to the tail. With a 35 hp engine it flew at 45 mph.

Most of the sales from the factory were to wealthy private owners who decided to take up flying. They bought a Wright, simply because it was a Wright and not because of any consideration of performance or utility of what was available. Other sales were to young men who wanted to earn money from demonstrating Wright aeroplanes though the brothers warned that ‘stunts and dangerous manoeuvres’ were not recommended. A number of the later models were used by the US Army and Navy as trainers.

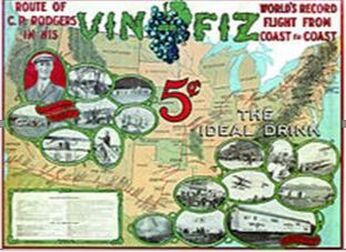

As aviation burst on the scene in 1910 many businesses saw an opportunity for publicity by offering prizes for some spectacular achievement. William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper magnate was one. He offered $50,000 for the first aviator to fly coast-to-coast across the USA in less than 30 days. Calbraith Perry Rodgers was one adventurer who took up the challenge. Already a keen yachtsman and motorcyclist he came to the Wrights Flying School and had 90 minutes of instruction from Orville.

He bought a Model B and persuaded the Armour Company to sponsor him. He would name his plane Vin Fiz after the grape soft drink they sold. His support team would travel in three railway cars. Packed in them was another Model B, lots of spares and tools, with sleeping accommodation and a shop, stocked with Vin Fiz. Rodgers would navigate by following the tracks. He invited Charlie to join him, not to fly, but as Chief Mechanic.

Orville didn’t want Charlie to go. Charlie had always wanted to learn to fly but the Wrights had refused to teach him. They suspected he would go off on a flying career and they would lose him.

Now he was being lured away by a wage of $70 a week (he was earning $25 at the time). Orville asked Charlie not to quit, just take the time off as leave of absence.

Rodgers and Charlie left Long Island on 17 September 1911. By 8 October, they had reached Chicago. Heading west meant crossing the barrier of the Rockies so Rodgers veered south, lengthening his journey. Finally, they reached California being welcomed at Pasadena on 5th November by a crowd of 20,000.

But there had been 75 stops on the way and 16 crashes, including several when Rodgers had suffered injuries. And only a few parts of the original Model B which left New York completed the trip. They were already 19 days past the 30 day deadline but Rodgers was determined to reach the Pacific coast.

He took off for Long Beach. On the way he crashed again, seriously. He spent three weeks in hospital with a brain concussion and a twisted spine.

In the end, he ceremoniously taxied into the sea at Long Beach to end his journey of over 4000 miles in a flying time of 84 hours.

The sad end to Calbraith Rodgers’ story came just four months later. Making an exhibition flight at Long Beach in the spare Model B which had crossed the States by train he flew into a flock of birds. Rodgers’ neck was broken when the biplane crashed into the sea.

On the epic journey to California Charlie’s wife had travelled as one of the support team. Shortly after they arrived she fell ill. They didn’t get back to Dayton until the autumn of 1912. Charlie found that much had changed. Wilbur had died and there were many new people at the factory. Orville became involved in the tangle of legal battles which never seemed to be settled. Withdrawing to the old office above the cycle shop he seldom visited the factory. In 1915 he decided to sell the company and in a series of mergers it was finally absorbed into the Curtis-Wright-Company.

In the clear up, the old 1908 Flyer was found in a shed. Wilbur had thought it only worth burning. Charlie and Orville refurbished it for a temporary exhibition in MIT, Cambridge, Mass. Afterwards, Orville refused to allow it to be displayed in the Smithsonian museum because they were displaying a machine hopped by Glenn Curtiss as the world’s first flier. So from 1928 to 1948 the Flyer was in the Science Museum in London.

In the clear up, the old 1908 Flyer was found in a shed. Wilbur had thought it only worth burning. Charlie and Orville refurbished it for a temporary exhibition in MIT, Cambridge, Mass. Afterwards, Orville refused to allow it to be displayed in the Smithsonian museum because they were displaying a machine hopped by Glenn Curtiss as the world’s first flier. So from 1928 to 1948 the Flyer was in the Science Museum in London.

Charlie worked at another factory in Dayton until 1919 when he moved to Los Angeles. He kept in touch with Orville and they exchanged letters every 17th December. In 1937, Henry Ford (who had decided that history was no longer bunk) hired detectives to find Charlie (he was working as a humble machinist earning 37 cents an hour).

Ford needed Charlie to help restore the old Wright home and cycle shop and move them to Ford’s museum in Michigan.

Charlie also built a replica of that first engine for the museum and here they are together (though this picture was taken in 1948).

At the end of WWII, Charlie suffered a heart attack and was never able to work again. An $800 annuity given to him by Orville was eroded by inflation and Charlie ended in a charity ward. He was discovered there by a reporter whose story brought him to the notice of the aviation industry. Funds were quickly raised to move Charlie to a more comfortable private home where he spent the last years of his life..

He died on 30 January 1956, eight years to the day after his employer and friend Orville Wright.

The Federal Aviation Administration now makes a presentation of the

Charles Taylor Master Mechanic Award

to those who qualify by having 50 years service in aviation

maintenance, having been an FAA-certificated mechanic for 30 years.