The Forgotten Air Race (July 2016)

If you were asked who won the Air Race to Australia you’d probably need no prompting to reply ‘Scott and Campbell Black in the Comet’. You’d be right, of course, provided the question referred to the 1934 race. But there was another one. 1969 was the 50th anniversary of Ross and Keith Smith’s flight in the Vickers Vimy in 1919. BP decided celebrate it by sponsoring an air race.

It was to be handicapped and there were three categories:

Class A – Single engine piston aircraft with a maximum take-off weight of

less than 5000lbs.

Class B – Non-supercharged multi-piston engine aircraft with a maximum

take-off weight of less than 12,500lbs.

Class C - Aircraft powered by super-charged piston or propeller turbine

engines with a maximum take-off weight of up to 12,500lbs.

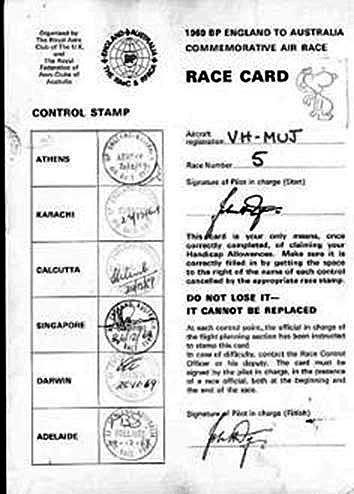

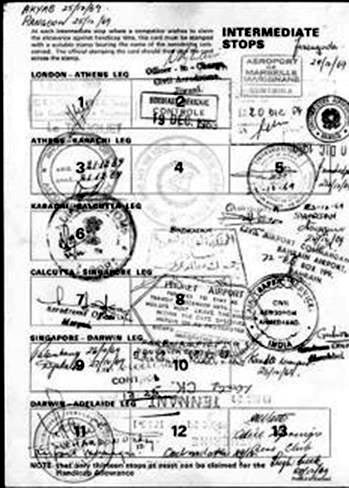

All competitors had to follow the 1919 route of the Vimy and make seven compulsory control point stops at Athens, Karachi, Calcutta, Singapore, Darwin, Alice Springs and Adelaide. The aircraft were due to reach Adelaide before Christmas 1969. The plan was for them to wait there until January 2nd for the final leg of the race from Adelaide to Sydney, where the overall winner would then be found on a basis of total time, according to handicap.

Entries flooded in. There were 77 in all plus a few who joined in for the fun of a ‘no rules’ race like a Fan Jet Falcon of the Canadian Armed Forces and a Hawker Siddeley HS.125 of Qantas.

Class A – Single engine piston aircraft with a maximum take-off weight of

less than 5000lbs.

Class B – Non-supercharged multi-piston engine aircraft with a maximum

take-off weight of less than 12,500lbs.

Class C - Aircraft powered by super-charged piston or propeller turbine

engines with a maximum take-off weight of up to 12,500lbs.

All competitors had to follow the 1919 route of the Vimy and make seven compulsory control point stops at Athens, Karachi, Calcutta, Singapore, Darwin, Alice Springs and Adelaide. The aircraft were due to reach Adelaide before Christmas 1969. The plan was for them to wait there until January 2nd for the final leg of the race from Adelaide to Sydney, where the overall winner would then be found on a basis of total time, according to handicap.

Entries flooded in. There were 77 in all plus a few who joined in for the fun of a ‘no rules’ race like a Fan Jet Falcon of the Canadian Armed Forces and a Hawker Siddeley HS.125 of Qantas.

Typical entrants were Mike Mahon and John Murray from Northern Ireland. They managed to get some sponsorship from the Belfast Telegraph and hired a Cherokee Arrow. To increase its range they arranged with Shorts to have an extra tank (an old hydraulic tank from a Short Belfast) fitted with a hand pump to transfer the fuel. Being doubtful that their navigational skills were up to the job they were lucky to spot an advert placed in a flying magazine by an RAF Squadron Leader, looking for a seat in the race. So Terry Nash became their third crew member. In the pre-race preparations the chat with other competitors made them worry again about fuel. So they bought some plastic containers and stored them in their hotel room. Other guests complained about the smell of petrol but they got them out of the back door the next morning without being discovered.

A Cherokee Arrow (not the one mentioned)

A Cherokee Arrow (not the one mentioned)

Other entrants assemble. The Prentice proves that any aeroplane could enter. It sits modestly in

the background, as well it might – it retired from ‘mechanical failure’

the background, as well it might – it retired from ‘mechanical failure’

Aero Commander and Shrike Commander

Two of the Beech brigade- the King Air and the Bonanza

The only military entrant came from the Army Air Corps. Major Mike Somerton-Rayner was well known in air racing circles. He had an Auster AOP 9 modified with extra fuel tanks, wheel spats and a coarse pitch propellor. A better radio was fitted and a civilian registration painted on the fin.

Here it is alongside a Rollason Condor. The Condor’s extra slipper tank is visible.

There were entries from several European countries, the USA, Kenya and Zambia. The majority of non-UK entrants were from Australia and New Zealand. They had their own problems and adventures in getting to the start line. For example . . .

John Wynn lived in Bendigo, a gold mining town in Victoria. He owned a little Victa Airtourer and had already flown around Australia. His next ambition was to fly to England and the BP race just accelerated his plans. He approached his friend and fellow pilot Keith Buttrey. Their discussion in the pub was overheard by two reporters. Immediately this pair became the self-appointed PR team for the venture. Soon there was eager sponsorship from the Mayor and the City of Bendigo, the Lions Club and even Qantas. The Airtourer was named Little Nugget and equipped with a tape recorder and film camera to send back regular reports to their supporters. Lions International clubs along the route were primed to offer hospitality and assistance.

They had an interesting flight with all the expected problems with the weather and navigation. The Lions contact both helped and hindered their progress. At some places they had difficulty in escaping from an endless round of dinners and visits and at others, club members were essential in helping to deal with local regulations. In Rangoon, they had to fill in thirty five declaration forms. It prepared them for India which they thought was even worse. At Ahmadabad there was a long wait until a doctor could be found to operate a spray to fumigate the aeroplane before they left. They were relieved to reach the gloom of an English winter and join the other competitors at Gatwick. To deepen the gloom, several of the crews were suffering from the onset of Asian flu.

John Wynn lived in Bendigo, a gold mining town in Victoria. He owned a little Victa Airtourer and had already flown around Australia. His next ambition was to fly to England and the BP race just accelerated his plans. He approached his friend and fellow pilot Keith Buttrey. Their discussion in the pub was overheard by two reporters. Immediately this pair became the self-appointed PR team for the venture. Soon there was eager sponsorship from the Mayor and the City of Bendigo, the Lions Club and even Qantas. The Airtourer was named Little Nugget and equipped with a tape recorder and film camera to send back regular reports to their supporters. Lions International clubs along the route were primed to offer hospitality and assistance.

They had an interesting flight with all the expected problems with the weather and navigation. The Lions contact both helped and hindered their progress. At some places they had difficulty in escaping from an endless round of dinners and visits and at others, club members were essential in helping to deal with local regulations. In Rangoon, they had to fill in thirty five declaration forms. It prepared them for India which they thought was even worse. At Ahmadabad there was a long wait until a doctor could be found to operate a spray to fumigate the aeroplane before they left. They were relieved to reach the gloom of an English winter and join the other competitors at Gatwick. To deepen the gloom, several of the crews were suffering from the onset of Asian flu.

Little Nugget at Gatwick. Note the unusual central two-handed control column.

The race was scheduled to begin on 17th December 1969 but the weather was so bad over Europe that the start was delayed until the following day. Two veterans of the England-Australia air route were there. Sir Francis Chichester had been invited to flag off the competitors and he was joined by Jean Batten, persuaded to emerge from reclusive retirement.

Only eight aircraft took off that day, the rest of the 72 left over the next two days. All had to contend with bad weather and icing and there were many landings scattered across Southern France and Italy, some pilots having to cope with landing in winds of 40 knots. At Brindisi, a Mooney tried three times to land safely before damaging a wingtip on its final touchdown. The strain was already taking its toll. The crew of an Australian Cessna 210 fell out so badly that they abandoned the race.

The weather, and Asian flu, were affecting Mike Somerton-Rayner too. The military markings on his Auster caused a diversion to avoid Syria and he was heading for Luxor in Egypt. Over Cairo, he was intercepted by a Mig-21 which, briefly, tried to formate on him. Then, suddenly, a portion of the exhaust split open and flames blew back under the fuselage. His feet were getting hot when the engine stopped. He had forgotten to change tanks so the absentmindedness was providential. When the engine stopped, the fire went out.

At Luxor, he found the broken exhaust still attached by a thin strip of metal. A taxi driver took him and the exhaust into town and found a welder. The welder made a temporary fix and also put Mike S-R up for the night. The next day he faced long, lonely legs across the Arabian desert before he re-joined the route at Karachi.

Only eight aircraft took off that day, the rest of the 72 left over the next two days. All had to contend with bad weather and icing and there were many landings scattered across Southern France and Italy, some pilots having to cope with landing in winds of 40 knots. At Brindisi, a Mooney tried three times to land safely before damaging a wingtip on its final touchdown. The strain was already taking its toll. The crew of an Australian Cessna 210 fell out so badly that they abandoned the race.

The weather, and Asian flu, were affecting Mike Somerton-Rayner too. The military markings on his Auster caused a diversion to avoid Syria and he was heading for Luxor in Egypt. Over Cairo, he was intercepted by a Mig-21 which, briefly, tried to formate on him. Then, suddenly, a portion of the exhaust split open and flames blew back under the fuselage. His feet were getting hot when the engine stopped. He had forgotten to change tanks so the absentmindedness was providential. When the engine stopped, the fire went out.

At Luxor, he found the broken exhaust still attached by a thin strip of metal. A taxi driver took him and the exhaust into town and found a welder. The welder made a temporary fix and also put Mike S-R up for the night. The next day he faced long, lonely legs across the Arabian desert before he re-joined the route at Karachi.

The crews met a variety of receptions when they landed in India. Where they were expected they were welcomed by crowds, refuelled quickly and not over-burdened with paperwork. At others, multiple forms appeared and delays tested their patience.

Sheila Scott was not having an easy race. She had autopilot problems but the failure of her radio was more serious. Bad weather ahead on the Singapore-Darwin leg caused her to divert to Macassar Island in Indonesia. A nearby crew (with working radio) was asked to join her there and fly on in formation.

Refuelling at Singapore

Sheila Scott was not having an easy race. She had autopilot problems but the failure of her radio was more serious. Bad weather ahead on the Singapore-Darwin leg caused her to divert to Macassar Island in Indonesia. A nearby crew (with working radio) was asked to join her there and fly on in formation.

Refuelling at Singapore

Flt Lts Kingsley and Evans (day job - Red Arrows pilots) landed in their SAIA Marchetti SF 260 (the picture is not the race aircraft). They left on Christmas Day in formation with Sheila Scott but the weather really was bad and they lost contact. The SF 260 landed on a beach on Flores Island. One crewman walked 6 miles to a nearby airfield. With generous local help the beach was reinforced with coconut leaves to allow a safe take off. They refueled at the airfield and left for Darwin.

Sheila Scott had landed at Sumbawa and had to wait for fuel. She did qualify as a finisher at Adelaide.

Sheila Scott had landed at Sumbawa and had to wait for fuel. She did qualify as a finisher at Adelaide.

Little Nugget had made reasonable progress during the race but their slow speed meant more hours in the air and John and Keith were both very tired. As they approached Darwin the weather got steadily worse. The sun had set, John was finding it hard to stay awake, becoming disorientated and finding it difficult to hold a heading. Keith slept through it all, ignoring John’s shakes and punches. The Darwin controller realized from John’s voice and the track on the radar that he was in trouble and gave him frequent guidance. He eventually had to tell John to ‘look down on the starboard side’ to help him see the lights of the airfield. John landed automatically and as he drew up in his parking place Keith woke up.

They made it to Adelaide in time. Their race card shows how many extra refueling stops they made.

They made it to Adelaide in time. Their race card shows how many extra refueling stops they made.

Of the 72 competitors who had been flagged off at Gatwick 58 made it to Adelaide. They enjoyed a well- earned rest and assembled again on 2 January for the final leg to Sydney.

Although the balbo which left Adelaide flew at different speeds there was inevitably serious congestion at Sydney. Anticipating this, three parallel runways had been marked out on the airfield. Pilots trying to call in for clearance to do their run over the field before joining the circuit found it nearly impossible to break into the stream of transmissions. Finally, Air Traffic gave up and issued a general instruction. ‘Left hand circuit, pick any runway 29 that’s clear’. Incredibly, everyone landed within 10 minutes and only 3 had to go round.

And, after all the excitement, who won? Answer - those who best beat the handicappers, plus all those awarded special prizes.

The overall winner, receiving the Prime Minister’s Trophy and the BP Australia Prize plus $A25,000, was a humble Islander, capably flown by Captains W J Bright and F Buxton. There were separate prizes for each of the different classes. Sheila Scott was 4th overall but was consoled with $A5000 and the All-Women’s Crew Trophy.

There were so many prizes on offer that some had to be combined. Capt T E Lampitt’s performance in his Beech 99 earned him $A10,000 - the New South Wales Government/Sir Ross and Sir Keith Smith/Capt Cook Bi-Centenary/ Dunlop Prize(s).

You probably don’t want to know who won the Trans-Australia Airlines, the Ansett Airlines, the Avis and the Stewart Smith Trophies but you might be interested to hear that both the Rolls Royce and the BAC Vickers Trophies were won by the slowest aircraft in the race, Little Nugget. However, there was no evident $A attachment.

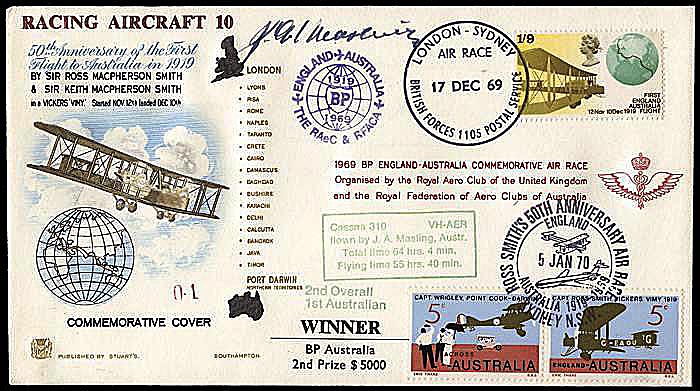

The race was recorded in other ways – a bit of aircraft adornment and a couple of first day covers.

Although the balbo which left Adelaide flew at different speeds there was inevitably serious congestion at Sydney. Anticipating this, three parallel runways had been marked out on the airfield. Pilots trying to call in for clearance to do their run over the field before joining the circuit found it nearly impossible to break into the stream of transmissions. Finally, Air Traffic gave up and issued a general instruction. ‘Left hand circuit, pick any runway 29 that’s clear’. Incredibly, everyone landed within 10 minutes and only 3 had to go round.

And, after all the excitement, who won? Answer - those who best beat the handicappers, plus all those awarded special prizes.

The overall winner, receiving the Prime Minister’s Trophy and the BP Australia Prize plus $A25,000, was a humble Islander, capably flown by Captains W J Bright and F Buxton. There were separate prizes for each of the different classes. Sheila Scott was 4th overall but was consoled with $A5000 and the All-Women’s Crew Trophy.

There were so many prizes on offer that some had to be combined. Capt T E Lampitt’s performance in his Beech 99 earned him $A10,000 - the New South Wales Government/Sir Ross and Sir Keith Smith/Capt Cook Bi-Centenary/ Dunlop Prize(s).

You probably don’t want to know who won the Trans-Australia Airlines, the Ansett Airlines, the Avis and the Stewart Smith Trophies but you might be interested to hear that both the Rolls Royce and the BAC Vickers Trophies were won by the slowest aircraft in the race, Little Nugget. However, there was no evident $A attachment.

The race was recorded in other ways – a bit of aircraft adornment and a couple of first day covers.