Corrigan and the Compass Conundrum (Apr 2022)

It was a quiet afternoon in July (1938) when a rather scruffy little aeroplane landed at Baldonnel airfield, Dublin. The pilot was walking towards the buildings when he met an army officer. ‘My name’s Corrigan – and I’ve just flown here from New York’. Oddly enough, the Irish already knew about him. An item in the morning newspaper said that an unknown flier had taken off from New York the day before and might be crossing the Atlantic.

The Customs Officer at Dublin didn’t know how to deal with him – he had no passport, no papers, and his only map was of the USA. Corrigan explained that he’d taken off in fog, flown into cloud and ‘must have misread his compass’. He was really heading for San Diego in California.

Thus ‘Wrong Way' Corrigan hit the world headlines.

Douglas Corrigan (22 Jan 1907 – 8 Dec 1995) was born in Texas of Irish parents. After they divorced he moved with his mother to Los Angeles. He was 18 when he paid $2.50 for his first flight. He was immediately hooked. He hung around the airfield, scraping together enough money for lessons, eventually flying solo. He managed to get a job with Ryan and Mahoney, a struggling company in San Diego, struggling because of some recently cancelled orders. Then, they got a new order, a special order - to build an aeroplane capable of flying the Atlantic. Charles Lindbergh, an airmail pilot, wanted to win the $25,000 Orteig Prize. Although the prize had been on offer for five years, no one had yet claimed it. Now, suddenly, there were several challengers building or modifying their chosen aeroplanes.

The Ryan company worked hard to meet Lindbergh’s deadline, often working till midnight. That could well be young Corrigan in the picture, fitting the wing to the Spirit of St Louis.

When Lindbergh reached Paris and won the prize all the workers at Ryan felt proud to have built this successful and now world famous aeroplane. Corrigan was inspired. He was a pilot too and knew that he could fly across an ocean. The Ryan company moved to St Louis, but Corrigan stayed in San Diego and got a job with Air Tech School.

When Lindbergh reached Paris and won the prize all the workers at Ryan felt proud to have built this successful and now world famous aeroplane. Corrigan was inspired. He was a pilot too and knew that he could fly across an ocean. The Ryan company moved to St Louis, but Corrigan stayed in San Diego and got a job with Air Tech School.

Whenever he could, he would borrow a company plane in his lunch hour and fly, practising any aerobatic manoeuvre the plane was capable of doing. He was soon banned from aerobatics, so he took to flying off across the Mexican border where his exuberant aviation was out of sight of the flying school and American authority. He needed a plane of his own.

It wasn’t until 1933 that he’d saved up enough - $345 - to buy a 1929 Curtis Robin. He went touring in it, landing by small towns and selling flights, barnstormer style. (In one landing, the undercarriage was damaged when he ran into a tree stump. He fixed it with a couple of pieces of scrap wood and some wire cut from a fence). He made enough money to buy a better engine for the Robin – actually it was a re-build with parts from two other engines - a 165 hp Wright J6-5, a 5-cylinder supercharged radial, similar to Lindbergh’s engine. He installed extra fuel tanks to hold enough to get him to his chosen destination, Dublin, of course. He had the aeroplane checked by a Federal Inspector who licensed it ‘for cross country flights’.

Douglas flew to New York and asked for permission to make his flight to Dublin. He was told to wait a year – and get a radio licence. He flew back to California, got the licence and installed another two fuel tanks. They had to be on, or near the CG, so they filled the space where the passenger would normally sit, completely blocking any view Corrigan would have to his right. He also gave his plane a name, Sunshine, which he painted on the cowling.

The year of waiting over, he applied again. His timing was bad. Amelia Earhart had just disappeared (in July, 1937) over the Pacific Ocean. Not only was he refused permission, they took one look at Sunshine and refused to renew his licence. Corrigan formed a plan. He would fly to New York, using small out of the way airfields, fill up all his tanks and take off at night, Dublin bound. It took him nine days, largely because of bad weather, which persisted after he reached New York. It was getting late in the year and wisely, he decided to fly home, non-stop. He almost made it. Headwinds, bouts of carburettor icing all delayed him, but eventually he sneaked into a little airport near Los Angeles. There was a Federal inspector there and Sunshine was grounded.

Grounded, but not inaccessible. Douglas spent six months giving aeroplane and engine a thorough overhaul. He applied for an inspection and was granted an Experimental licence. There were restrictions with this licence so he also applied for, and was granted, permission to make a non-stop flight to New York and a non-stop return to San Diego. He did some consumption tests and worked out that his most economical flying speed was 85 mph.

He was ready to go on 7th July, 1938. Turbulence over the mountains, dust storms over the desert, thunderstorms over the plains, he flew straight through them all with no diversion. Towards the end of the trip, his main fuel tank developed a leak. Douglas pressed on, sticking his head out of the window to avoid the fumes and keep awake. 27 hours after take off, he landed in New York. There were only four gallons of fuel left in the tank.

Fixing the leak would be a big job. All the other tanks would have to come out to get at the main tank. Corrigan worked out that he would have enough fuel for his next flight if he used the leaking tank first. If he did run out, he could land anyway before he reached San Diego. He flew to Floyd Bennett Field, the New York field with the longest runway. He asked the airfield manager which runway he should use. He was told ‘Any one you like, providing it’s not the one towards my office’ – that was at the western end of the long runway.

At 4 ‘o clock on the misty morning of 17th July, Corrigan used his torch for the pre-flight inspection, started his engine and used most of the 1300 metre runway 06 to get airborne – Sunshine was loaded with 320 US gallons of fuel. He flew into cloud and set course for his destination. What was his destination?

The year of waiting over, he applied again. His timing was bad. Amelia Earhart had just disappeared (in July, 1937) over the Pacific Ocean. Not only was he refused permission, they took one look at Sunshine and refused to renew his licence. Corrigan formed a plan. He would fly to New York, using small out of the way airfields, fill up all his tanks and take off at night, Dublin bound. It took him nine days, largely because of bad weather, which persisted after he reached New York. It was getting late in the year and wisely, he decided to fly home, non-stop. He almost made it. Headwinds, bouts of carburettor icing all delayed him, but eventually he sneaked into a little airport near Los Angeles. There was a Federal inspector there and Sunshine was grounded.

Grounded, but not inaccessible. Douglas spent six months giving aeroplane and engine a thorough overhaul. He applied for an inspection and was granted an Experimental licence. There were restrictions with this licence so he also applied for, and was granted, permission to make a non-stop flight to New York and a non-stop return to San Diego. He did some consumption tests and worked out that his most economical flying speed was 85 mph.

He was ready to go on 7th July, 1938. Turbulence over the mountains, dust storms over the desert, thunderstorms over the plains, he flew straight through them all with no diversion. Towards the end of the trip, his main fuel tank developed a leak. Douglas pressed on, sticking his head out of the window to avoid the fumes and keep awake. 27 hours after take off, he landed in New York. There were only four gallons of fuel left in the tank.

Fixing the leak would be a big job. All the other tanks would have to come out to get at the main tank. Corrigan worked out that he would have enough fuel for his next flight if he used the leaking tank first. If he did run out, he could land anyway before he reached San Diego. He flew to Floyd Bennett Field, the New York field with the longest runway. He asked the airfield manager which runway he should use. He was told ‘Any one you like, providing it’s not the one towards my office’ – that was at the western end of the long runway.

At 4 ‘o clock on the misty morning of 17th July, Corrigan used his torch for the pre-flight inspection, started his engine and used most of the 1300 metre runway 06 to get airborne – Sunshine was loaded with 320 US gallons of fuel. He flew into cloud and set course for his destination. What was his destination?

He always insisted that he meant to fly to San Diego but got lost in the mist and clouds and misread his compass. Few people believed him. How could his misread his compass to that extent? He wasn’t a few degrees out. He flew in entirely in the opposite direction. The newspapers thought it a great joke.

Yet all aviators know that ‘flying the reciprocal’ is the most common of compass errors. The north seeking needle looks exactly like the south seeking needle. It has to do, because the needle is balanced on a pin and free to swing round in response to the gentle pull of the earth’s magnetism. (The ‘needles’ might be printed on a card which floats on a bath of liquid but the same principle applies). Of course, the north seeking needle is marked in some way with a colour or a little luminous dot. That might help, except that the compass is the only pilot’s instrument that has to be mounted horizontally, which means it’s usually in the gloomy depths of the cockpit down by his ankle.

Fortunately, by WWII the direction indicator had been invented. This is a gyroscopic instrument that simply detects change of direction. It does not detect the earth’s magnetic field. The pilot uses his compass to establish his heading and sets that on the D I. Here the course is 200º. Any change of course is detected by the D I and it will show the new heading. Simple. However, the compass can’t be ignored because the D I suffers from gyroscopic precession and can wander. It must be checked against the compass at intervals.

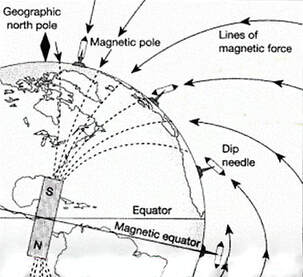

Douglas Corrigan did not have the advantage of this instrument. His was a simple compass which suffered from all the aspects of a compass’s unusual behaviour. The earth’s magnetic pole is not at the geographical pole – it’s somewhere deep underground near Ellesmere Island in Northern Canada. And it moves about. So an up-to-date aeronautical chart is needed to show the current variation, i.e the difference between magnetic north and true north, which can be as much as 11º.

Douglas Corrigan did not have the advantage of this instrument. His was a simple compass which suffered from all the aspects of a compass’s unusual behaviour. The earth’s magnetic pole is not at the geographical pole – it’s somewhere deep underground near Ellesmere Island in Northern Canada. And it moves about. So an up-to-date aeronautical chart is needed to show the current variation, i.e the difference between magnetic north and true north, which can be as much as 11º.

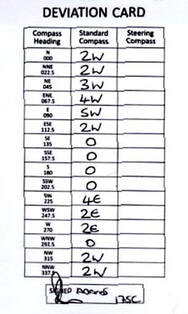

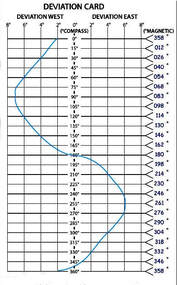

Another adjustment is needed. The compass sits inside an airframe made of many metal parts, not least the engine, all of which have a magnetic attraction which deflects the compass needle. So the compass has to be ‘swung’. Many airfields have a pattern like this painted on the tarmac in a quiet corner of the field. The main point is lined up with true north. The aeroplane is taxied into position so that it is pointing true north, then the compass is read. Even allowing for the variation the compass reading will be wrong by 2 or 3 degrees. That’s all the metal bits in the airframe.

It’s all because of something called compass dip. The compass needle aligns itself with the lines of the earth’s magnetic flux which emanate from that deeply underground earth magnet.

A freely suspended needle would show the degree of dip but that’s of no interest to a navigator. So the needle is hung from a point above its CG so that its weight keeps the needle level and it cannot react to the dip.

To turn onto a new course, say from North to NE, the pilot banks the aeroplane to the right. The needle and its plane of rotation are no longer level and the dip pulls the needle down the slope. The compass card swings to the right and shows an apparent turn to the left. (If he had been heading south before starting the turn the dip of the north-seeking needle would show an increased rate of turn). Pilots were sometimes taught techniques to compensate for the compasses turning errors. Usually they were ignored. They can rely on their Direction Indicator which does not suffer from magnetic dip and gives an accurate reading of heading.

To turn onto a new course, say from North to NE, the pilot banks the aeroplane to the right. The needle and its plane of rotation are no longer level and the dip pulls the needle down the slope. The compass card swings to the right and shows an apparent turn to the left. (If he had been heading south before starting the turn the dip of the north-seeking needle would show an increased rate of turn). Pilots were sometimes taught techniques to compensate for the compasses turning errors. Usually they were ignored. They can rely on their Direction Indicator which does not suffer from magnetic dip and gives an accurate reading of heading.

The pilots most affected by magnetic dip are those flying sailplanes. They spend a lot of time circling in thermals, their compasses looping and swinging about uselessly. They want to leave the thermal heading in the right direction, particularly if they are in a race. Often they can’t see the sun or check on some prominent point on the ground. With a normal compass they would have to straighten up and wait patiently for the agitated needle to settle down, often to tell them that they’re on the wrong track. Happily, a clever chap called Harry Cook devised a little compass whose needle was mounted on a spindle. Attached to the panel by a single bolt it could be turned so that the spindle was vertical, unaffected by dip and giving correct readings in the continuously circling glider.

The standard compass has other moments of aberration. Head East and accelerate (open the throttle or dive). Inertia makes the hanging needle swing backwards, the plane of rotation slopes, the needle swings down and the compass says you’ve turned left. (Head West, accelerate and ‘turn’ right).

The standard compass has other moments of aberration. Head East and accelerate (open the throttle or dive). Inertia makes the hanging needle swing backwards, the plane of rotation slopes, the needle swings down and the compass says you’ve turned left. (Head West, accelerate and ‘turn’ right).

Lindberg had another compass. One of the latest types of compass was fitted to the Spirit of St Louis. It had been developed by the Pioneer Instrument Company and was called an Earth Inductor Compass. (It was the first Direction Indicator).

This is a model of the Spirit. No photographs of the real Spirit show clearly enough that little ring of cups which rotated in the airstream. It spun a wire coil, which interacted with the earth’s magnetic field to produce an electric current which varied according to direction of the field. (Actually, it just detected the north-south line. A second coil, set at an angle worked out which end was north). So Lindbergh had the luxury of reading a very clear instrument, unaffected by ‘dip’, mounted on the panel right in front of him.

This is a model of the Spirit. No photographs of the real Spirit show clearly enough that little ring of cups which rotated in the airstream. It spun a wire coil, which interacted with the earth’s magnetic field to produce an electric current which varied according to direction of the field. (Actually, it just detected the north-south line. A second coil, set at an angle worked out which end was north). So Lindbergh had the luxury of reading a very clear instrument, unaffected by ‘dip’, mounted on the panel right in front of him.

We must assume Douglas Corrigan knew about compasses and how easy it was to get an incorrect reading. All his previous flights had been overland and he navigated principally by map reading. But he had given a lot of thought, if not proper planning, to his dream of an over-the-ocean flight to Dublin. It hadn’t involving having a map.

When he took off on that misty morning he knew the course to fly to San Diego. It was 245º and he had his maps of the US to check on his progress. His tanks were full. 340 gallons was more than enough to get him to San Diego, 2370 miles away. Was that enough to reach Dublin, 3200 miles away – if he flew a straight course. And if the leak in his main tank didn’t drain away too much fuel. He wrote a book after his flight and explained what happened.

After the long, long take off Sunshine’s rate of climb was agonisingly slow. By the time he judged he was high enough to avoid bumping into any skyscrapers he was in cloud, flying blind on limited instruments – turn and slip, altimeter and air speed indicator. He turned gently. But his compass didn’t react properly. It wasn’t the usual turning error – it showed no turn at all. The compass card seemed to be stuck. He realised that some of the liquid must have drained out of the compass and the card wasn’t floating freely. He had another compass. It was under the panel, down by his knees and he had set the course for San Diego on it - 245º. All he had to do was line up the needle with the lines on the glass. It wasn’t daylight yet and the compass was in shade.

The reciprocal of 245º is 065º. Well, the course for Dublin is 050º and Europe is a pretty wide target.

The few people who had watched Douglas take off saw him disappearing into the mist, heading East. Some had heard his chat about an early morning take off when no officials were around, flying out of US airspace ‘where the rules didn’t apply’. He ‘couldn’t be hung for it’ was his joke. He had been seen over Long Island, flying east. He had been to the weather centre at Mitchell Field the day before to check on the weather over the States. He had not asked about, nor been told anything about the weather over the Atlantic. But, just in case, an official warning was issued to all shipping in the Atlantic to look out for a little aeroplane heading for Europe.

Douglas had climbed steadily to 3,000 ft and was flying between cloud layers. There was a brief break in the cloud. Down below was a city. (It was Boston and he was spotted by someone who told a newspaper reporter). But it could have been Baltimore, on the route to San Diego. The cloud closed in before he could be sure.

Ten hours later the cloud layer still obscured the earth and his feet were getting cold. Petrol from the leak was sloshing over the cockpit floor. Some must be dribbling out – and there was a hot exhaust pipe under the port side of the fuselage. Douglas found a screwdriver in his tool kit and stabbed a hole in the floor on the starboard side away from that hot exhaust. He was flying at 85 mph, 1600 rpm, the speed for best fuel consumption. He decided to increase the revs to 1900. It would use up more fuel before it leaked out and he’d be flying faster.

It was 26 hours after take off before the cloud cleared and he could see the ground – the ocean. There was no doubt now about which way he was flying and it was far too late to turn round. He flew on.

He saw a fishing boat – he couldn’t be far from land. In celebration, he opened his bag of provisions. He worked his way through two packets of fig biscuits and was just starting on the chocolate when green hills came into sight. Ireland!

He flew across Ireland, ignored Belfast (‘couldn’t see any airfield’), turned south and landed at Baldonnel, Dublin 28 hours and 13 minutes after take off. It was quite a performance. He’d flown 3200 miles at an average speed of 114 mph (he must have picked up some tailwind) with no navigational chart or aids (apart from that simple compass with all its idiosyncrasies) and in a very second hand barely serviceable aeroplane. His hero, Lindbergh, who was much better prepared and equipped, flew 3600 miles in 33½ hours – 107 mph.

When he took off on that misty morning he knew the course to fly to San Diego. It was 245º and he had his maps of the US to check on his progress. His tanks were full. 340 gallons was more than enough to get him to San Diego, 2370 miles away. Was that enough to reach Dublin, 3200 miles away – if he flew a straight course. And if the leak in his main tank didn’t drain away too much fuel. He wrote a book after his flight and explained what happened.

After the long, long take off Sunshine’s rate of climb was agonisingly slow. By the time he judged he was high enough to avoid bumping into any skyscrapers he was in cloud, flying blind on limited instruments – turn and slip, altimeter and air speed indicator. He turned gently. But his compass didn’t react properly. It wasn’t the usual turning error – it showed no turn at all. The compass card seemed to be stuck. He realised that some of the liquid must have drained out of the compass and the card wasn’t floating freely. He had another compass. It was under the panel, down by his knees and he had set the course for San Diego on it - 245º. All he had to do was line up the needle with the lines on the glass. It wasn’t daylight yet and the compass was in shade.

The reciprocal of 245º is 065º. Well, the course for Dublin is 050º and Europe is a pretty wide target.

The few people who had watched Douglas take off saw him disappearing into the mist, heading East. Some had heard his chat about an early morning take off when no officials were around, flying out of US airspace ‘where the rules didn’t apply’. He ‘couldn’t be hung for it’ was his joke. He had been seen over Long Island, flying east. He had been to the weather centre at Mitchell Field the day before to check on the weather over the States. He had not asked about, nor been told anything about the weather over the Atlantic. But, just in case, an official warning was issued to all shipping in the Atlantic to look out for a little aeroplane heading for Europe.

Douglas had climbed steadily to 3,000 ft and was flying between cloud layers. There was a brief break in the cloud. Down below was a city. (It was Boston and he was spotted by someone who told a newspaper reporter). But it could have been Baltimore, on the route to San Diego. The cloud closed in before he could be sure.

Ten hours later the cloud layer still obscured the earth and his feet were getting cold. Petrol from the leak was sloshing over the cockpit floor. Some must be dribbling out – and there was a hot exhaust pipe under the port side of the fuselage. Douglas found a screwdriver in his tool kit and stabbed a hole in the floor on the starboard side away from that hot exhaust. He was flying at 85 mph, 1600 rpm, the speed for best fuel consumption. He decided to increase the revs to 1900. It would use up more fuel before it leaked out and he’d be flying faster.

It was 26 hours after take off before the cloud cleared and he could see the ground – the ocean. There was no doubt now about which way he was flying and it was far too late to turn round. He flew on.

He saw a fishing boat – he couldn’t be far from land. In celebration, he opened his bag of provisions. He worked his way through two packets of fig biscuits and was just starting on the chocolate when green hills came into sight. Ireland!

He flew across Ireland, ignored Belfast (‘couldn’t see any airfield’), turned south and landed at Baldonnel, Dublin 28 hours and 13 minutes after take off. It was quite a performance. He’d flown 3200 miles at an average speed of 114 mph (he must have picked up some tailwind) with no navigational chart or aids (apart from that simple compass with all its idiosyncrasies) and in a very second hand barely serviceable aeroplane. His hero, Lindbergh, who was much better prepared and equipped, flew 3600 miles in 33½ hours – 107 mph.

The Irish authorities weren’t sure how to handle this illegal immigrant. He told his tale to everyone he met, all the way up to the American ambassador and the Irish Prime Minister. They all responded with ‘Now tell us the real story’. From the US came a 600 word telegram listing all the regulations he had broken – and suspending his licence for 14 days, which just happened to be the day he arrived back in the States.

Sunshine in Dublin

Sunshine in Dublin

He came home on the USS Manhattan and is said to have signed autographs for all the 1000 passengers and 500 crew. When the ship arrived in New York it was met by fireboats streaming arcs of water. He got a rapturous reception, even a ticker tape parade. A million people lined the streets to cheer him, more, they said, than Lindbergh.

There was another parade at Floyd Bennett Field where he was presented with the first of many compasses. He toured the country, in Sunshine, of course to many receptions, met the President and had breakfast with senior members of the Civil Aviation Authority, whose regulations he had flouted. He wrote his book ‘That’s My Story’ and starred in a film ‘The Flying Irishman’.

Despite all the fame and acclamation Douglas Corrigan was a shy and private man. His only interest was flying and this he continued to do. During the war he delivered planes with Ferry Command and also flew as a production test pilot with Douglas.

Despite all the fame and acclamation Douglas Corrigan was a shy and private man. His only interest was flying and this he continued to do. During the war he delivered planes with Ferry Command and also flew as a production test pilot with Douglas.

He retired from flying in 1950 and bought an orange grove which he ran with his wife and three sons. Sunshine went into storage, re-emerging in 1988 in time for the Golden Anniversary celebrations of the flight – and here it is with Douglas. It now sits in the Planes of Fame Air Museum at Chino, California.

Douglas died in 1995, insisting to the end that his flight was genuinely the result of misreading the compass.

Yet he lives on. ‘Wrong way’ and ‘Doing a Corrigan’ have entered the language with their own special meaning. And every year, on 17th July, countless parties and celebrations are held across America on Wrong Way Corrigan Day.

Douglas died in 1995, insisting to the end that his flight was genuinely the result of misreading the compass.

Yet he lives on. ‘Wrong way’ and ‘Doing a Corrigan’ have entered the language with their own special meaning. And every year, on 17th July, countless parties and celebrations are held across America on Wrong Way Corrigan Day.