Early Days at Heathrow (Aug 2011)

Back in 1946 the country was shaking off its wartime gloom. Although money was short there was a massive building programme under way to equip London with a decent airport. The old Great West Aerodrome, a grass field intended to be used by Fairey Aviation for testing its aircraft had been requisitioned by the Air Ministry in 1944 and they began to build runways for bombers. But the war ended with only one of its three runways completed and the Ministry of Aviation took it over on 1 January 1946 to develop it into the new London Airport.

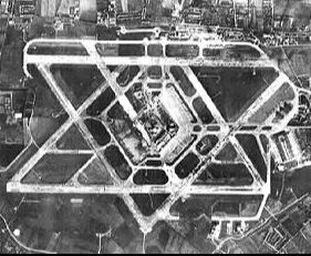

The runways were deemed to be quite inadequate and plans were produced for six 3000 yard runways in a Star of David pattern. In the middle of the building programme the first commercial flight took off on 25 March 1946 when a British South American Airways Lancastrian left for Buenos Aries. Even though it was declared ‘fully’ open on 31 May the airport was woefully short of equipment and completely devoid of terminal buildings.

A major problem was its inability to cope with poor weather, in particular the fogs which, in the days long before any clean air legislation were real pea-soupers and could linger for days. There was SBA of course, the wartime Standard Beam Approach which transmitted a radio beam in line with the runway. The pilot detected deviation left or right if the continuous note in his headphones changed to the Morse code A or N. But there was no help to monitor height other than a couple of marker beacons which gave a burst of signal to tell the pilot when he should have been at a predetermined altitude. If he was at the wrong height he overshot or hoped that, as a last resort, he could catch sight of the white Very lights being fired into the murk by the runway control caravan. Pilots familiar with LAP admitted that they relied on spotting the Peggy Bedford pub on Bath Road as a really reliable fix.

A more effective Instrument Landing System was being developed. This transmitted signals were displayed on a cockpit instrument by needles which showed the direction and angle of the proper approach path together with the amount of any deviation so that the pilot could adjust his course and rate of descent continuously. However, few aeroplanes were fitted with ILS receivers and, more significantly, the system in its early form was very temperamental and over-sensitive to interference. London’s ILS could be disabled even by the reflections from an unwitting cyclist passing the transmitter.

The runways were deemed to be quite inadequate and plans were produced for six 3000 yard runways in a Star of David pattern. In the middle of the building programme the first commercial flight took off on 25 March 1946 when a British South American Airways Lancastrian left for Buenos Aries. Even though it was declared ‘fully’ open on 31 May the airport was woefully short of equipment and completely devoid of terminal buildings.

A major problem was its inability to cope with poor weather, in particular the fogs which, in the days long before any clean air legislation were real pea-soupers and could linger for days. There was SBA of course, the wartime Standard Beam Approach which transmitted a radio beam in line with the runway. The pilot detected deviation left or right if the continuous note in his headphones changed to the Morse code A or N. But there was no help to monitor height other than a couple of marker beacons which gave a burst of signal to tell the pilot when he should have been at a predetermined altitude. If he was at the wrong height he overshot or hoped that, as a last resort, he could catch sight of the white Very lights being fired into the murk by the runway control caravan. Pilots familiar with LAP admitted that they relied on spotting the Peggy Bedford pub on Bath Road as a really reliable fix.

A more effective Instrument Landing System was being developed. This transmitted signals were displayed on a cockpit instrument by needles which showed the direction and angle of the proper approach path together with the amount of any deviation so that the pilot could adjust his course and rate of descent continuously. However, few aeroplanes were fitted with ILS receivers and, more significantly, the system in its early form was very temperamental and over-sensitive to interference. London’s ILS could be disabled even by the reflections from an unwitting cyclist passing the transmitter.

A more reliable approach aid was Ground Controlled Approach which used radar housed in a truck strategically parked in line with the runway in use. But all the available GCA units were in the hands of the RAF and there was no trained civilian crew. So the Ministry of Aviation asked the RAF if they could borrow one of their units for a few months to keep London Airport working. Most of them were in Germany. In the UK the busiest RAF airfields were reluctant to give up their excellent approach aid. So the spotlight inevitably fell on No 12 GCA which was languishing at Prestwick on the Scottish coast south of Glasgow.

Prestwick had been a busy transatlantic terminal during the war but this traffic had dwindled. The GCA unit was almost the last RAF presence on the airfield and many of their customers were civilian or US aircraft requesting approaches for practice or just interested in trying out the new experience of being talked down to landing. There was another factor. The area had an excellent weather record. In the severe winter of 1946-47, when there were 20 feet deep snowdrifts in Yorkshire, Prestwick had suffered only one night of closure because of weather. It hardly justified the sophisticated approach aid.

Life was very comfortable for the small independent unit. The 5-strong operating crew were retrained ex-aircrew and there was a small group airmen - mechanics, drivers, D/F operators etc. The only formal gathering was the fortnightly pay-parade - actually just a queue outside the orderly room. Their shift system was jealously guarded. A crew was on 24 hour duty from 1 pm to 1 pm but from 5 pm to 8 am they were on 1-hour standby (spent in the canteen or anywhere else within Tannoy-shot). The following 24 hours was entirely free of duty. Every third weekend a crew was off duty for 3 days plus, of course, the half day at each end of the break. The CO saw no reason why off-duty airmen should clutter up the camp so he freely handed out leave passes on request.

Nevertheless, the work was interesting because of the variety of aeroplanes which used the airfield. Scottish Aviation had been a busy wartime servicing base and although they had specialized on Liberators they had a wide range of types still in their hangars. Sadly, most were being made flyable just to be flown away for scrapping. One of these appeared at what could have been an embarrassing time.

Life was very comfortable for the small independent unit. The 5-strong operating crew were retrained ex-aircrew and there was a small group airmen - mechanics, drivers, D/F operators etc. The only formal gathering was the fortnightly pay-parade - actually just a queue outside the orderly room. Their shift system was jealously guarded. A crew was on 24 hour duty from 1 pm to 1 pm but from 5 pm to 8 am they were on 1-hour standby (spent in the canteen or anywhere else within Tannoy-shot). The following 24 hours was entirely free of duty. Every third weekend a crew was off duty for 3 days plus, of course, the half day at each end of the break. The CO saw no reason why off-duty airmen should clutter up the camp so he freely handed out leave passes on request.

Nevertheless, the work was interesting because of the variety of aeroplanes which used the airfield. Scottish Aviation had been a busy wartime servicing base and although they had specialized on Liberators they had a wide range of types still in their hangars. Sadly, most were being made flyable just to be flown away for scrapping. One of these appeared at what could have been an embarrassing time.

Dwight Eisenhower was the current European Supreme Commander and one day he arrived at Prestwick to spend a brief holiday at nearby Culzean Castle. His shiny Douglas C-54 had taxied off to its secure parking spot when the accompanying entourage arrived in a pink Dakota, sorry, C-47. The brief-case lugging group, like the Dak, clad in pink, clustered on a convenient balcony below the tower which was built on top of the Orangefield Hotel. At this point, a tattered Lancaster scheduled for scrapping, taxied up. It had been stripped of anything useable, turrets removed and roughly faired over, no radio, etc. The pilot requested take-off clearance with a thumbs up. He noticed the laughing audience. Getting a green light he moved onto the runway and held on the brakes. The engines were revved furiously and the whole plane shook and rattled. When the brakes were released, the tail was up almost immediately and the lightweight Lanc leapt into the air and climbed steeply away. The American astonishment was very gratifying.

Not the Icelandic Lib but a similar conversion

Not the Icelandic Lib but a similar conversion

Liberators were a common sight at Prestwick since Scottish Aviation had been the main contractor for equipping and servicing the RAF’s Coastal Command fleet. Post war, some had returned to the US but others had been sold and converted to carry passengers. One of these, operated by Iceland Airways, took off from Prestwick for Reykjavik. As it left the ground a passenger noticed a link in the port undercarriage break. When this was reported to the pilot he realized that he couldn’t carry out a safe landing on that leg and that he would have to do a belly landing.

But not before he had got rid of much of his fuel load. Unfortunately, the Liberator had no fuel jettison system. The only course was to burn it off. They flew south to Preston then back to Prestwick - several times. For what was probably the longest four hours of their lives, the passengers looked forward to the uncertain prospect of a belly landing in an 18 ton aeroplane. The pilot elected to use nearby Heathfield, a grass field used by the Fleet Air Arm and conveniently close to Prestwick’s servicing facilities. The landing was entirely successful. One passenger did sprain his ankle by leaping out too eagerly but there were no other injuries and the Lib was repaired to fly again.

But not before he had got rid of much of his fuel load. Unfortunately, the Liberator had no fuel jettison system. The only course was to burn it off. They flew south to Preston then back to Prestwick - several times. For what was probably the longest four hours of their lives, the passengers looked forward to the uncertain prospect of a belly landing in an 18 ton aeroplane. The pilot elected to use nearby Heathfield, a grass field used by the Fleet Air Arm and conveniently close to Prestwick’s servicing facilities. The landing was entirely successful. One passenger did sprain his ankle by leaping out too eagerly but there were no other injuries and the Lib was repaired to fly again.

Scottish Aviation also decided to go into the airline business. Before the war they had bought a Fokker F-XXII, a 4-engined monoplane carrying 22 passengers. This had been impressed into RAF service and was returned to Scottish in 1945. They began to use it as a Belfast shuttle. It certainly made its presence felt when it took off. Its power units were 4 Pratt & Whitney Wasps, the same engine as used by the Harvard trainer. It made plenty of noise but no money and was grounded in 1947.

Meanwhile, the fog-bound London Airport was embarrassing the Ministry of Aviation and 12 GCA’s comfortable posting came to an end early in 1947. Their departure somehow came to the notice of the Scottish press and there was an outburst of indignant anti-English articles and cartoons about the ’poaching’ of Scotland’s only radar approach facility. It was to no avail, of course. Heathrow’s need was greater than Prestwick’s and the unit migrated south for the winter.

When they arrived, Heathrow was the scene of frenzied activity – largely of a huge building force of diggers, concrete makers and sub-contractors. They were frantically transforming the standard wartime triangular pattern of three runways into a six-runway complex with extensive terminal buildings inconveniently isolated in the centre. The runways were designed to cope with the largest passenger and freight aircraft being planned for the future. A significant indicator was the Bristol Brabazon airliner expected to fly in 1948. With an all-up weight of 130 tons sitting on two huge single mainwheels its arrival needed a runway of some resilience. And what other, even heavier, aeroplanes might be on the drawing boards?

So Mr Wimpey started by digging a hole 30 feet deep. The bottom layer of the runway consisted of very large blocks of stone – just one block per lorry – with smaller compacted blocks above until finally the runway surface emerged from the mud.

So Mr Wimpey started by digging a hole 30 feet deep. The bottom layer of the runway consisted of very large blocks of stone – just one block per lorry – with smaller compacted blocks above until finally the runway surface emerged from the mud.

The airport operated on whichever runway was complete but mostly on 10/28. Close to this runway was Heathrow North, the temporary terminal, an untidy sprawl of marquees and duckboards alongside the northern perimeter track. Passengers, despite being well-heeled and able to afford air travel, were expected to re-live the wartime spirit and ‘rough it’.

Visiting aeroplanes had equally casual treatment. They were parked on any convenient paved area and maintenance was carried out in the open. This Constellation enjoyed a blaze of publicity when it arrived on Pan-American’s first round-the-world scheduled flight. Nevertheless the maintenance crew had to take all their equipment and ladders to where it sat on the grass alongside the peri-track.

As well as shiny new civil aeroplanes Heathrow was host to many converted war-surplus bombers. They were going cheaply and, with a plywood pannier under the bomb-bay, as on this Halifax, they could carry sufficient cargo to earn a living. They spawned a rash of new ‘airlines’ set up by entrepreneurs keen to make their mark in what many believed would be a rapidly expanding aviation business. There certainly was money to be made importing the sort of goods which had been absent from the British market during the war years – Mediterranean fruit, for instance

12 GCA set up its stall on a small hard standing at the upwind end of the runway in use. Usually this was at the eastern end of runway 28 but when the wind changed a little caravan of trucks and trailers trundled round the airfield to its new location. At some points there was an electricity supply but one truck carried a large diesel generator which made the unit self-sufficient. The capabilities of GCA might have been ‘cutting edge’ for the time but they were, by later standards, rather primitive.

The rotating aerial (on the roof at the forward end) displayed all the air traffic up to a range of 30 miles. The screen display – with ample ground returns - was somewhat imprecise and there was no indication to tell the Controller which aeroplane he was talking to. So a radio Direction Finding truck was parked nearby. Between the bursts of crackling from the unshielded ignition systems of the passing builders’ lorries the D/F operators would confirm the bearing of the transmitting aeroplane. Then, to make sure, the Controller would ask the pilot to make a 90º turn ‘for identification’. At last he could direct his chosen blip to a convenient point some 10 miles from the runway.

This early model of GCA needed a large crew. The elevation and azimuth aerials swept continuously over a narrow angle and their returns were monitored by separate operators who tracked the blip of the aeroplane with a cursor. The cursors’ positions were repeated on another display used by the Approach Controller to ‘talk down’ the approaching aeroplane. Once it was established on the correct path he told the pilot not to acknowledge any further instructions and began a running commentary of any heading or rate of descent corrections needed. In the final stages, to ensure a clear and quickly updated return, the aerials were switched to rapid movement and the whole truck vibrated with noisy excitement until the Controller said ‘A quarter of a mile from the runway - look ahead for the runway and land’.

Despite the urgency of the request to bring the unit to Heathrow there was a marked lack of interest from the customers. Air Traffic regularly offered their new service and it was almost always declined – until one day of soggy fog with gently falling snow. A Lancastrian of Don Bennett’s British South American Airways was on its last leg home from Lisbon. The pilot refused GCA and insisted on his familiar SBA approach. Several attempts resulted in overshoots. He saw neither runway 28 or the succession of white Very lights being fired by the runway controller.

Changing to r/w 10 was equally unsuccessful. Even the Peggy Bedford pub was invisible. The time came for diversion to another airfield - or GCA. Reluctantly, he opted to be talked down. The controller’s final instruction to ‘Look ahead for the runway’ coincided conveniently with a break in the falling snow. The runway appeared in the windscreen and the relieved pilot landed. He was so overcome by the experience that he came round the airfield to inspect the GCA truck and shake the hands of his saviours. He told all his friends and colleagues and as the word spread, requests for a GCA approach – even in fine weather – became the norm. The operators looked back on their relaxed life at Prestwick with wistful nostalgia.

It didn’t always go well. A Belgian pilot approaching in genuine fog drifted off line and was told to overshoot. He replied ‘It’s OK. I got it’ and landed – rolling along the peritrack past the tented terminal. Luckily, no other aeroplane or vehicle was in the way. (A less happy repeat of this occurred shortly after Heathrow’s civilian GCA crew took over. A Viking diverted from fog-bound Northolt missed the approach and crashed into a pile of drain pipes).

There was another noteworthy incident – not involving GCA or fog. The pilot of a Halifax didn’t like the strong crosswind on runway 28 and opted to use another runway which had recently been completed. Nevertheless, the crosswind caused the Halifax to swing and the starboard wheel went over the runway’s edge. At this point the ground had not yet been levelled and the mud was nearly a foot lower than the tarmac. All might have been well but the Halifax met a cross runway and struck its lip with a bang. At the far side of the runway, the wheel crashed down on the rough ground again and the undercarriage leg gently folded. The grounded wing tip swung the disintegrating Halifax through 180º.

Despite the urgency of the request to bring the unit to Heathrow there was a marked lack of interest from the customers. Air Traffic regularly offered their new service and it was almost always declined – until one day of soggy fog with gently falling snow. A Lancastrian of Don Bennett’s British South American Airways was on its last leg home from Lisbon. The pilot refused GCA and insisted on his familiar SBA approach. Several attempts resulted in overshoots. He saw neither runway 28 or the succession of white Very lights being fired by the runway controller.

Changing to r/w 10 was equally unsuccessful. Even the Peggy Bedford pub was invisible. The time came for diversion to another airfield - or GCA. Reluctantly, he opted to be talked down. The controller’s final instruction to ‘Look ahead for the runway’ coincided conveniently with a break in the falling snow. The runway appeared in the windscreen and the relieved pilot landed. He was so overcome by the experience that he came round the airfield to inspect the GCA truck and shake the hands of his saviours. He told all his friends and colleagues and as the word spread, requests for a GCA approach – even in fine weather – became the norm. The operators looked back on their relaxed life at Prestwick with wistful nostalgia.

It didn’t always go well. A Belgian pilot approaching in genuine fog drifted off line and was told to overshoot. He replied ‘It’s OK. I got it’ and landed – rolling along the peritrack past the tented terminal. Luckily, no other aeroplane or vehicle was in the way. (A less happy repeat of this occurred shortly after Heathrow’s civilian GCA crew took over. A Viking diverted from fog-bound Northolt missed the approach and crashed into a pile of drain pipes).

There was another noteworthy incident – not involving GCA or fog. The pilot of a Halifax didn’t like the strong crosswind on runway 28 and opted to use another runway which had recently been completed. Nevertheless, the crosswind caused the Halifax to swing and the starboard wheel went over the runway’s edge. At this point the ground had not yet been levelled and the mud was nearly a foot lower than the tarmac. All might have been well but the Halifax met a cross runway and struck its lip with a bang. At the far side of the runway, the wheel crashed down on the rough ground again and the undercarriage leg gently folded. The grounded wing tip swung the disintegrating Halifax through 180º.

The crash vehicles arrived but the ambulance was not needed - the crew members were unhurt. As they left the scene another van rushed up. The driver was carrying only a paint pot and brush and he quickly set to work obliterating the airline’s name. The Halifax’s cargo had been strewn across the ground when the wooden pannier was scraped off. It was not worth saving but was only too readily accessible to the GCA crew parked nearby. For a few days they suffered seriously from a surfeit of Spanish peaches.

The RAF’s brief appearance at Heathrow came to an end after six busy months and 12 GCA made the return journey to Scotland, not to Prestwick, but back to service life at RAF Leuchars on the east coast.