King’s Cup Air Race - 1952 (Jan 2021)

The King’s Cup air race originated in 1922 – the King being George V. Its aim was to encourage the development of light aircraft and suitable engines. It promised to be more fun that the Trials for Light Aeroplanes with tiny engines that the Daily Mail and the Air Ministry were going to hold in 1923.

The race would be held annually and was open to Commonweath pilots only. It would be a handicap race round a circuit of Great Britain. For 1922, the 810 mile route started and finished at Croydon with an overnight stop in Glasgow. Most of the 22 entrants flew powerful war surplus machines and quite a few managed to complete the circuit. Enormous crowds collected at Croydon and also at the other refuelling points to see little more than a few landings and take offs.

It was not necessarily the fastest aeroplane that stood the best chance of winning. Before the race every machine was carefully examined by the Royal Aero Club handicappers, knowledgeable engineers and pilots, who checked power, wing loading and other factors. They aimed to predict the aeroplane’s racing speed.

The race would be held annually and was open to Commonweath pilots only. It would be a handicap race round a circuit of Great Britain. For 1922, the 810 mile route started and finished at Croydon with an overnight stop in Glasgow. Most of the 22 entrants flew powerful war surplus machines and quite a few managed to complete the circuit. Enormous crowds collected at Croydon and also at the other refuelling points to see little more than a few landings and take offs.

It was not necessarily the fastest aeroplane that stood the best chance of winning. Before the race every machine was carefully examined by the Royal Aero Club handicappers, knowledgeable engineers and pilots, who checked power, wing loading and other factors. They aimed to predict the aeroplane’s racing speed.

They set different take-off times for every aeroplane. Other things being equal, if everything went to plan all the competitors would arrive at the finishing line time together.

The winner of this first race was Frank Barnard, Chief Pilot of Instone Air Line. He flew a DH 4A (an ex-bomber converted to carry two passengers in an enclosed cabin fitted where the gunner used to sit). It was the aeroplane he used in his day job.

The King’s Cup, the only air race to have royal patronage, became the premier fixture in the air sports calendar. The list of winners included Alan Cobham in 1924, Richard (Batchy) Atcherley in 1929, the year in which he flew in the Schneider Trophy team, Geoffrey de Havilland in 1933 and Alex Henshaw in 1938, shortly before his epic flight to Cape Town and back in the Mew Gull in which he had won the King’s Cup.

The second World War interrupted the races and they didn’t restart until 1949. The post-war skies were more crowded and the long-distance circuit was abandoned. Now competitors would complete several laps of a short circuit, with pylons marking the turning points. Often the sheer number of eager entrants had to be pruned in a series of qualifying races.

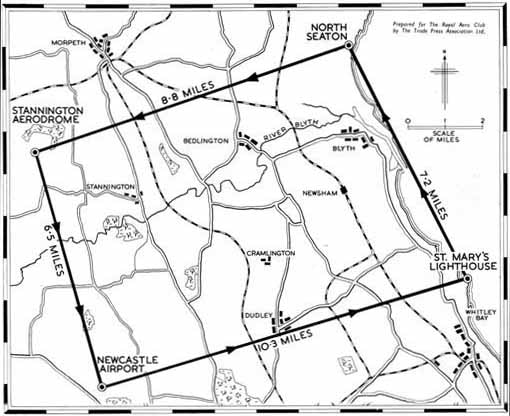

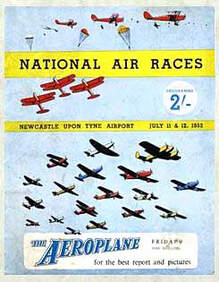

This was the case in 1952 when the 20th King’s Cup race was held at Woolsington, Newcastle’s airport. The race itself would be four laps of a four turning point course, 32.8 miles per lap totalling 131.2 miles. Three qualifying two-lap heats reduced the number of finalists to 23. The heats were flown on the Friday when there were other races for the Grosvenor Challenge Cup and the Kemsley Challenge Trophy.

The second World War interrupted the races and they didn’t restart until 1949. The post-war skies were more crowded and the long-distance circuit was abandoned. Now competitors would complete several laps of a short circuit, with pylons marking the turning points. Often the sheer number of eager entrants had to be pruned in a series of qualifying races.

This was the case in 1952 when the 20th King’s Cup race was held at Woolsington, Newcastle’s airport. The race itself would be four laps of a four turning point course, 32.8 miles per lap totalling 131.2 miles. Three qualifying two-lap heats reduced the number of finalists to 23. The heats were flown on the Friday when there were other races for the Grosvenor Challenge Cup and the Kemsley Challenge Trophy.

The latter featured a plethora of Percival Proctors which occupied the first three and the last three places. There were a couple of Miles Geminis and upholding the name of de Havilland – but only in fifth place - was a Vampire, entered by Gp. Capt. John Cunningham, no less, but flown by J M Wilson. What an interesting race that must have been. (That looks like J.C. in the background in the picture below).

The final on Saturday 12th July was supported by an air show and attracted a huge crowd of spectators. Also on show and to present the prizes was the guest of honour, Field Marshal Montgomery, in genial mode.

The final on Saturday 12th July was supported by an air show and attracted a huge crowd of spectators. Also on show and to present the prizes was the guest of honour, Field Marshal Montgomery, in genial mode.

In the morning there was time to look at and photograph many of the racing and visiting aeroplanes.

This is an Erco Ercoupe, designed to be foolproof and ‘as easy to fly as driving a car’. The rudders were coupled to the ailerons so that a simple turn of the steering wheel produced a balanced turn. The elevator up movement was restricted not only making it difficult to stall but also ‘self-landing’. It worked and there were several instances of non-pilots taking control in an emergency. (One was stolen by two 10 year old boys who landed safely after a cross country flight).

Bristol had just completed the restoration of this F.2B. and they showed it off here before handing it over to Shuttleworth.

Its presence provided an excuse for some executives to come in their shiny new Sycamore, the first British helicopter to be awarded a Certificate of Airworthiness.

Some of the competitors-

A couple of Miles Whitney Straights – an odd name for an aeroplane. No 38 flew in the Grosvenor Trophy race on Friday. No 41 would come 20th in the King’s Cup, flown by Bill Bedford, one of Hawker Siddeley’s test pilots. He went on to develop the P1127-Kestrel-Harrier family.

A couple of Miles Whitney Straights – an odd name for an aeroplane. No 38 flew in the Grosvenor Trophy race on Friday. No 41 would come 20th in the King’s Cup, flown by Bill Bedford, one of Hawker Siddeley’s test pilots. He went on to develop the P1127-Kestrel-Harrier family.

{Whitney Willard Straight was born in New York in 1912. His father fought in France in WWI but died in the great Flu Epidemic in 1918. His mother then married an Englishman and the family moved to England when Whitney was 12. Whilst still an undergraduate he took up motor racing, eventually forming his own team and winning the 1934 South African GP – the race which ended Richard Shuttleworth’s motor racing career in 1936 when he was seriously injured. Straight was an avid aviator and formed a corporation which ran airfields and flying clubs. In 1936, (in which he became a naturalised Briton) he asked Fred Miles to build him a two-seat tourer with side by side seating. Other orders came in for ‘an aeroplane built to the Whitney Straight specification’ and the name stuck. To complete this brief biography Straight went on the serve in the RAF, fought in the Battle of Britain and ended as an Air Commodore. He joined British European Airways and later became CEO and Deputy Chairman of BOAC. He died in 1979}.

A Hawk Speed Six - Miles made just three of these pure racing aeroplanes. This one, G-ADGP, was entered by Ron Paine – he finished 7th.

It flew in several King’s Cups from 1933 to 1960 and now sits proudly in the Shuttleworth hangars. Proudly because this aircraft still holds the FAI Class C.16 100km. closed circuit record at 192.83 mph.

There can’t be an air race without a Moth of some sort and there were several Tigers. This is a rarer Gipsy Moth, rather unfairly registered G-ABAG. It came 9th in Friday’s Grosvenor Cup.

Another Moth, genus Leopard, and with a Norwegian registration. Capt Christie took it to 5th place in the Norton-Griffiths Challenge Trophy. Don’t sneer at 5th - the Hawk Speed Six was 10th and last.

This is an Avro Club Cadet. To understand where it fits in you have to go back to the Avro Tutor (240 hp Lynx), used by the RAF and other air forces as a basic trainer (Shuttleworth has one). Avro saw a market for a smaller, cheaper-to-operate trainer and produced the Cadet (135 hp Genet radial). This was indeed ordered by the Irish Air Corps and the RAAF.

A version with folding wings was built for civilian clubs. This particular one has a 130 hp Gipsy Major. It was flown at Woolsington by David Ogilvy who was General Manager at Shuttleworth for some 30 years. He won the Grosvenor Challenge Cup on the Friday and finished 9th in the King’s Cup on the Saturday.

A version with folding wings was built for civilian clubs. This particular one has a 130 hp Gipsy Major. It was flown at Woolsington by David Ogilvy who was General Manager at Shuttleworth for some 30 years. He won the Grosvenor Challenge Cup on the Friday and finished 9th in the King’s Cup on the Saturday.

Over 1000 Hawker Harts were built (not counting the many variants) and the last one flying, at least until 1971, was G-ABMR. Here it is taking off in Friday’s Kemsley Trophy race flown by Frank Bullen, another one of Hawker’s test pilots. In the King’s cup he finished 18th.

The King’s Cup race was scheduled to start at 2.30 pm and the crowd were all herded behind the barriers (a single rope on simple stakes) to watch the frenzied polishing and final tweaking of the racing aircraft. Fuel was measured precisely – just enough for the race and emergencies, no excess weight). The spectators were given an explanation of the rules, the course and the handicapping system so that they understood why the crews of some of the faster aeroplanes seemed to be in no hurry, completely disinterested, sitting on the grass and chatting.

First to leave was Beverly Snook’s Tiger – 15th

G.C.Marler in the Falcon Six – 4th

The 4th turning point was on the airfield and we could compare the turning techniques of the pilots. They all aimed to get round as quickly as possible and used spectacular angles of bank. The slower an aeroplane flies, the greater its rate of turn. So some pilots have experimented pulling up the nose to slow down for a quick turn, then diving down to gain extra speed after the turn. It can’t be overdone, or even done at all when other aeroplanes and creeping up from behind to overtake.

Fred Dunkerley in his Gemini. Air racers call themselves throttle benders. They certainly cane their engines in racing and when Fred turned onto his second lap a trace of smoke could be seen behind his port engine. On the next lap the engine was still smoking and one undercarriage leg was dangling. The Gemini has an electric u/c retracting mechanism – the connection isn’t obvious. A true racer to the end, Fred finished the race – in 22nd place – and landed safely.

As the race went on, the faster aeroplanes began to catch up with the slower group and by the time the leaders had started on their fourth and final lap the spectators could see this snarling sausage shaped gaggle. And then, at last, 59 minutes and 33 seconds since the flag fell for Beverley Snook, the heavily handicapped Vampire took off.

The gaggle faded from view, heading for the turning point on the coast. The next aircraft to come into view was the Vampire, screaming round the pylon in a wide turn. Four minutes later, it was back in another tight turn on to the third lap. Another four minutes the Vampire, still on its own was off on its last lap chasing that little swarm of gnats the spectators could now see in the distance on the final leg. The gnats resolved into aeroplanes, one or two of which were slightly ahead of the main group diving down towards the ground to wring out that extra knot.

Just clear of the ground, No 12 crossed the line first.

It was Cyril Gregory in his Taylorcraft Plus D.

Right behind him was the Proctor of G.R. ‘Sailor’ Parker (the Buccaneer’s test pilot).

It was Cyril Gregory in his Taylorcraft Plus D.

Right behind him was the Proctor of G.R. ‘Sailor’ Parker (the Buccaneer’s test pilot).

At that crucial point my camera ran out of film. So the sight of that sky full of jostling aircraft, dramatically pierced by the Vampire (average speed 458 mph) which sliced right through them, is recorded only in memory. They were so close that all seemed to cross the line together (tribute to the handicappers) and the time of the 20th was within seconds of the 3rd.

After the race there was an entertaining air show. It began with a flypast by the Vampires of the local squadron, 607, based at the nearby RAF Ouston. The Navy followed with a formation of four Attackers, one of which dangled his hook in a slow flypast. Almost as fast as the Attacker was the high speed flypast of a Slingsby Sky, an advanced competition glider one of which had won the World Championship a few weeks before.

The highlight of the show was undoubtedly the appearance of the de Havilland Comet which was displayed by John Cunningham. Showing off the livery of BOAC with which it had just come into service it roared over the cheering spectators.

Encouraged by the commentator the crowd throbbed with nationalistic pride, admiring the world’s first jet-powered swept wing airliner.

Sadly, it would be only four months later that the first crash on take off at Rome would open the chapter of accidents that led to the Comet’s downfall. But that was in the unknown future and could have had no effect on the excitement and delight in having seen and enjoyed the graceful display of this beautiful aeroplane.

There was only a tinge of nationalism in the presence of another display team. The French Air Force formed their first team in 1935, known as a demonstration en Patrouille (on patrol). After WWII they used Stampe trainers (alright, they were Belgian). They came to Woolsington in 1952 and gave a formidable display of formation aerobatics. This is their solo act. Two months before, the commander of a squadron of Republic F-84 jet fighters had put on a display at his base in Algeria. The commentator was so excited he called it the Patrouille de France. It was goodbye to the Stampes.

The crowd were to enjoy another aerobatic display that was even more appreciated by the watching pilots who understood what was being done and how difficult it was. The aeroplane was a Bücker Jungmeister – the Pitts Special of its day – and the pilot was a Prince Constantin Cantacuzeno.

{He was a member of the Cantacuzeno dynasty which had ruled Romania for centuries. In the thirties he flew as Chief Pilot of LARES, the Romanian Air Transport Company. He was also a keen aerobatic pilot and became National Champion in 1939, flying his Jungmeister. On the outbreak of war, he joined the Air Force and flew in a squadron equipped with Mk I Hurricanes. Romania had been ‘absorbed’ by Hitler so their troops went to war against the Russians.

By 1943, Cantacuzeno was commander of a squadron equipped with Me 109s and building a tidy score of victories, enough to be awarded the Iron Cross, First Class. He became ill and spent some months in hospital returning in time to meet the USAAF raids against the oilfields around Ploesti in which he shot down a B-24 Liberator.

In August 1944 Romania decided to stop fighting with the Germans and they opted for an Axis-Exit. The affronted Germans still had some airfields in Romania and began bombing Bucharest. Cantacuzeno added three He 111s and an Fw 190 to his score (he ended with 43 confirmed victories, Romania’s highest).

With the Russians in control life was becoming difficult. There were many US airmen PoWs, technically freed but unable to get back to Allied controlled territory i.e. Italy. Without any authorisation Cantacuzeno secretly had an Me 109G prepared with an extra fuel tank and the radio removed from its compartment in the fuselage behind the wing root. Into this he squeezed Lt Col. James Gunn who had briefed him on the landing procedures at Foggia. When they arrived there Cantacuzeno put on his lights and lowered the undercarriage, rocking his wings. They landed without being fired on. Cantacuzeno borrowed a screwdriver, opened the little 18” square hatch and produced Gunn.

Subsequently, Cantacuzeno was briefed on flying a Mustang and he led a formation of P-51s back to his airfield in Romania. (He couldn’t resist a burst of Mustang aerobatics before landing). They were followed by groups of B-17s, stripped of interior fittings, each of which could cram in 20 ex-PoWs. 700 Americans were rescued that day and the ferrying went on until 1,161 had been evacuated.

Cantacuzeno himself stayed in Romania but he was steadily stripped of all his possessions and status. In 1947 he managed to get away, eventually to Spain where he took a job crop dusting. After a short spell of bankruptcy he was able to raise enough money to buy one of his beloved Jungmeisters and make a living from display flying, which is how he managed to be in Newcastle in 1952. It didn’t last long. Surgery for an ulcer went wrong and he died in 1958, aged just 53}.

By 1943, Cantacuzeno was commander of a squadron equipped with Me 109s and building a tidy score of victories, enough to be awarded the Iron Cross, First Class. He became ill and spent some months in hospital returning in time to meet the USAAF raids against the oilfields around Ploesti in which he shot down a B-24 Liberator.

In August 1944 Romania decided to stop fighting with the Germans and they opted for an Axis-Exit. The affronted Germans still had some airfields in Romania and began bombing Bucharest. Cantacuzeno added three He 111s and an Fw 190 to his score (he ended with 43 confirmed victories, Romania’s highest).

With the Russians in control life was becoming difficult. There were many US airmen PoWs, technically freed but unable to get back to Allied controlled territory i.e. Italy. Without any authorisation Cantacuzeno secretly had an Me 109G prepared with an extra fuel tank and the radio removed from its compartment in the fuselage behind the wing root. Into this he squeezed Lt Col. James Gunn who had briefed him on the landing procedures at Foggia. When they arrived there Cantacuzeno put on his lights and lowered the undercarriage, rocking his wings. They landed without being fired on. Cantacuzeno borrowed a screwdriver, opened the little 18” square hatch and produced Gunn.

Subsequently, Cantacuzeno was briefed on flying a Mustang and he led a formation of P-51s back to his airfield in Romania. (He couldn’t resist a burst of Mustang aerobatics before landing). They were followed by groups of B-17s, stripped of interior fittings, each of which could cram in 20 ex-PoWs. 700 Americans were rescued that day and the ferrying went on until 1,161 had been evacuated.

Cantacuzeno himself stayed in Romania but he was steadily stripped of all his possessions and status. In 1947 he managed to get away, eventually to Spain where he took a job crop dusting. After a short spell of bankruptcy he was able to raise enough money to buy one of his beloved Jungmeisters and make a living from display flying, which is how he managed to be in Newcastle in 1952. It didn’t last long. Surgery for an ulcer went wrong and he died in 1958, aged just 53}.

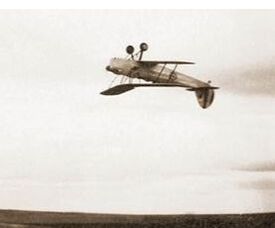

The Jungmeister first flew in 1935 and was designed specifically for aerobatics. With a wingspan of 21 ft 8 ins and a 160 hp engine it displayed ‘astonishing agility’. The combination of such a powerful engine in a tiny airframe was unusual for its day and the pilot could make full use of gyroscopic effects to produce manoeuvres that seemed impossible.

(In 1952, colour film was expensive and more expense was added if you wanted an enlargement. So this is a cheat. You could buy little tubes of transparent oil paint and delicate stroking with a cotton bud and other little tricks produced this effect).

(In 1952, colour film was expensive and more expense was added if you wanted an enlargement. So this is a cheat. You could buy little tubes of transparent oil paint and delicate stroking with a cotton bud and other little tricks produced this effect).

Cantacuzeno added his own modifications to his Jungmeister. The rudder was extended to allow him to do his signature manoeuvre. Note also that much smaller wheels had been fitted. The usual larger and heavier wheels must have had some adverse effect in one of the manoeuvres.

The display itself was quite dazzling and the little machine twirled about. The loops were tight and the ‘slow’ rolls not slow. The only bit of straight and level flight was a long sideslip with the wings rolled 90° and the nose held up with that enlarged rudder.

Finally he approached to land just in front of the crowd, the engine now quietly muttering. At the last second when no more than 10 feet above the ground, the engine roared, the plane climbed to 50 feet and flick rolled. Cantacuzeno closed the throttle and gently landed.

Fortunately, I’d been warned about this and was able to capture it with my little camera.

The camera I had at the time was an odd thing called a Purma Special. It used the standard 120 film but took square pictures so that I got 12 pictures from a roll. Unusually, it had a focal plane shutter.

A curtain moved across the film to open the shutter and a second curtain followed to close it. More expensive cameras could adjust the timing of the second curtain to give a range of exposure times. The cheap and cheerful Purma was different. A little weight was added to the second curtain. A simple spring produced a shutter speed of 1/100 of a second. With the basic fixed aperture lens that would be fine for most pictures taken on a normal bright day.

The clever bit was that if you turned the camera 90° to the right the extra weight on the second curtain would have to be lifted by the spring. The shutter speed was now 1/25. 90° to the left and gravity would speed up the curtain drop (1/450). So I know that flick roll picture was taken at 1/450 second and the wingtips are still blurred which says something about the speed of rotation of the little Jungmeister.

A curtain moved across the film to open the shutter and a second curtain followed to close it. More expensive cameras could adjust the timing of the second curtain to give a range of exposure times. The cheap and cheerful Purma was different. A little weight was added to the second curtain. A simple spring produced a shutter speed of 1/100 of a second. With the basic fixed aperture lens that would be fine for most pictures taken on a normal bright day.

The clever bit was that if you turned the camera 90° to the right the extra weight on the second curtain would have to be lifted by the spring. The shutter speed was now 1/25. 90° to the left and gravity would speed up the curtain drop (1/450). So I know that flick roll picture was taken at 1/450 second and the wingtips are still blurred which says something about the speed of rotation of the little Jungmeister.