Airlift from Sulaymaniya

(Apr 2020)

The First World War was a global conflict and there were many places other than France which were fought over. An ally of Germany and Austria-Hungary was Turkey and it suffered the loss of its Ottoman Empire which had controlled much of south-western Asia since the 14th century. Allied forces, under General Allenby cleared the Turks from much of which we now call the Middle East.

The Arab peoples living there hoped to establish their own free self-governing nations. For their co-operation during the fighting they had been ‘promised’ independence. They were not a homogenous group. Although predominantly Muslim the Shias and the Shi’ites interpreted the Koran differently and couldn’t live in harmony. Then there were the Kurds who always strove for their own independent territory. For the time being, the victorious Western Allies, Britain and France, imposed military governments based on a map which had been drawn up in secret in 1916.

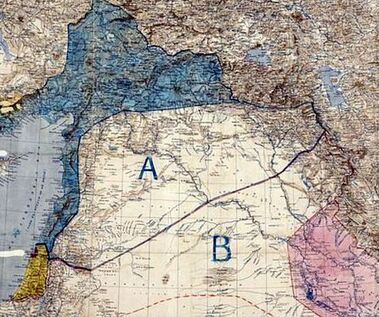

Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot had represented their governments as experienced colonial administrators. They both believed that, after the war, the peoples of the Middle East would be better off as part of an Empire, the French and British empires, naturally. Their proposed areas of influence France (A) and Britain (B) were drawn on a map with china-graph pencils – and here is the very map.

The Arab peoples living there hoped to establish their own free self-governing nations. For their co-operation during the fighting they had been ‘promised’ independence. They were not a homogenous group. Although predominantly Muslim the Shias and the Shi’ites interpreted the Koran differently and couldn’t live in harmony. Then there were the Kurds who always strove for their own independent territory. For the time being, the victorious Western Allies, Britain and France, imposed military governments based on a map which had been drawn up in secret in 1916.

Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot had represented their governments as experienced colonial administrators. They both believed that, after the war, the peoples of the Middle East would be better off as part of an Empire, the French and British empires, naturally. Their proposed areas of influence France (A) and Britain (B) were drawn on a map with china-graph pencils – and here is the very map.

It was the basis, with minor modifications, of the Treaty of Sèvres which was drawn up in 1920. Syria and Iraq (the old Mesopotamia plus extra bits) emerged as separate countries – governed under mandate by France and Britain respectively. The Kurds were promised their own country – later.

The ink was hardly dry on the treaty before thousands of Sunni and Shia swallowed their differences and rose up against the British. 14,000 British soldiers, plus 90,000 Indian troops and levies fought a fluid war. The part played by the RAF, dropping 97 tons of bombs and firing 180.000 rounds of ammunition, proved particularly effective.

The rebellion was put down and more than 9,000 Iraqis died. The cost was hundreds of British and Indian dead and several million pounds. RAF casualties were nine killed and seven wounded.

The ink was hardly dry on the treaty before thousands of Sunni and Shia swallowed their differences and rose up against the British. 14,000 British soldiers, plus 90,000 Indian troops and levies fought a fluid war. The part played by the RAF, dropping 97 tons of bombs and firing 180.000 rounds of ammunition, proved particularly effective.

The rebellion was put down and more than 9,000 Iraqis died. The cost was hundreds of British and Indian dead and several million pounds. RAF casualties were nine killed and seven wounded.

The whole affair greatly strengthened Trenchard’s case for using the RAF as the primary instrument for keeping the peace using fewer men and much less money. At a conference in Cairo in 1921, which Churchill attended as Secretary of State for the Colonies, Trenchard’s plan was officially adopted. (And in the end, it did work in out successfully. British military expenditure in Iraq in 1921 was £23 million. In 1925, it was less than £4 million).

Trouble soon flared up again, this time with the Kurds. They felt the Treaty of Sèvres had dealt them the worst hand. Their traditional territory was now swallowed, mostly by Iraq as well as a part in Turkey. In July, 1922 a local tribal chief, Kerim-Fattah-Beg began assembling a force to attack anything or anyone associated with British attempts to establish control over the region. Two officers sent out to negotiate with him were shot. A column of a Sikh regiment, Levies and some mountain artillery chased Kerim and his cavalry. The RAF assisted with reconnaissance and occasional bombing but Kerim managed to escape capture. After some weeks of constant movement and fighting in the summer heat, the column became weakened by sickness and loss of equipment and withdrew towards Sulaymaniya. From the airstrip there, the sick and injured were flown to Hinaida, the main RAF base near Baghdad.

Trouble soon flared up again, this time with the Kurds. They felt the Treaty of Sèvres had dealt them the worst hand. Their traditional territory was now swallowed, mostly by Iraq as well as a part in Turkey. In July, 1922 a local tribal chief, Kerim-Fattah-Beg began assembling a force to attack anything or anyone associated with British attempts to establish control over the region. Two officers sent out to negotiate with him were shot. A column of a Sikh regiment, Levies and some mountain artillery chased Kerim and his cavalry. The RAF assisted with reconnaissance and occasional bombing but Kerim managed to escape capture. After some weeks of constant movement and fighting in the summer heat, the column became weakened by sickness and loss of equipment and withdrew towards Sulaymaniya. From the airstrip there, the sick and injured were flown to Hinaida, the main RAF base near Baghdad.

Hinaidi – and, 170 miles away - Sulaymaniya.

There were reports of Turkish forces moving into Iraq and increasing numbers of Kurds were joining Kerim’s forces. It was evident that Sulaymaniya could not be defended. The small number of British and Indian troops and civilians would have to be evacuated, together with those Kurds who had actively worked with them. It would have to be done quickly and the only way was by air.

So it was that at 1230hrs on 4 September 1922 Sqn Ldr Edye Rolleston Manning MC, OC of Hinaidi based 6 Squadron, was ordered to fly to Sulaymaniya and arrange the evacuation the following day.

It took him four hours to set in place what was needed to receive the evacuees and locate and assign aircraft, mostly DH9As. Then he chose a competent aircraft mechanic and got him to assemble any essential tools and equipment which could be loaded into his Bristol Fighter. At 1630 he took off, accompanied by two other Brisfits. They arrived at Sulaymaniya at 1850hrs.

The ‘airfield’ was little more than a cleared area of rough ground on the outskirts of the town. At 2,900 ft amsl performance of the 1920s engines would be significantly reduced. Situated at the base of a range of steep mountains it was a daunting place. Pilots taking off towards the mountains were facing only a looming wall of craggy cliffs - an intimidating prospect.

Manning’s first priority was to order the local transport officer to have 1,000 gallons of fuel at the field by the following morning. As darkness fell, he positioned the Brisfits so that their guns were facing the town. The Levies formed a defensive ring around the perimeter. The RAF men slept under the wings of the aircraft.

Manning’s first priority was to order the local transport officer to have 1,000 gallons of fuel at the field by the following morning. As darkness fell, he positioned the Brisfits so that their guns were facing the town. The Levies formed a defensive ring around the perimeter. The RAF men slept under the wings of the aircraft.

During the night, a strong wind arose which threatened the operation. It promised to be very turbulent but at least, would shorten the ground run of aeroplanes taking off and landing.

Out in the country somewhere were a political official and an RAF officer and, separately an agricultural officer. At 0500hrs next morning, Manning sent out one of the Brisfits to locate them. As a breakfast of coffee and eggs was being hurriedly consumed the first of the people to be evacuated began arriving. There were 67 in all, including women and children. Manning gave priority to any mothers and children and also husbands and wives. Kurds, Jews and Persians would be next, then Indians, Europeans and finally the small number of Assyrian Levies who had elected to leave.

Out in the country somewhere were a political official and an RAF officer and, separately an agricultural officer. At 0500hrs next morning, Manning sent out one of the Brisfits to locate them. As a breakfast of coffee and eggs was being hurriedly consumed the first of the people to be evacuated began arriving. There were 67 in all, including women and children. Manning gave priority to any mothers and children and also husbands and wives. Kurds, Jews and Persians would be next, then Indians, Europeans and finally the small number of Assyrian Levies who had elected to leave.

At 0625, the first of the aircraft from Hinaidi arrived – four DH 9As. They didn’t offer much passenger accommodation, but a Persian man and wife and two babies were fitted into a gunner’s cockpit. Soon two more DH9As arrived. On landing, a crosswind gust swung one round, a tyre burst and the tailskid was damaged. Manning’s mechanic decided that he could repair it.

In the next 45 minutes, 10 more DH9As appeared. Two of them were badly damaged when they landed heavily in the gale. So badly that they could not be repaired. Happily, neither pilot was injured.

In the next 45 minutes, 10 more DH9As appeared. Two of them were badly damaged when they landed heavily in the gale. So badly that they could not be repaired. Happily, neither pilot was injured.

Back at Hinaidi, two Vickers Vernons had arrived from Egypt. The pilots were immediately flown to Sulaymaniya to assess whether their Vernon could land there. Normally, Vernons were powered by 250 hp Rolls Royce Eagle engines. It was fortunate that these particular Vernons had been re-engined with Napier Lions which produce 450 hp and that made the difference. The pilots promptly took them to Sulaymaniya. One of the Vernons took 12 passengers: in the other 19 passengers and a dog were squeezed.

The Brisfit searching for the officials out in the country returned and dropped a message. It had picked up the agricultural officer and was taking him to Hinaidi. The other two were reported to be heading for the Persian border.

It was a busy airfield. Aeroplanes were being refuelled, loaded and at times were taking off at five minute intervals. Passengers waiting their turn were kept busy helping with the refuelling and tyre changing. Because of the gale, wing walkers were needed to help the aeroplanes taxi-ing. The wind continued to blow, strongly enough to demolish the windsock and its pole. The canvas continued to do its job by being stretched out on the ground and held down by rocks.

All this activity was attracting the attention of the townspeople and a crowd assembled alongside the airfield swelling to over two thousand. Manning had aircraft parked strategically so that their guns covered the excited crowd. The fifteen Levies were not finding it easy to control them. Manning tried to avoid spreading any impression of panic and deliberately slowed down the pace of the operation, stopping anyone from rushing about. By 0900 most of the civilians had left.

After the last passengers had gone the aircraft were loaded with bombs, detonators and guns. A wireless n.c.o. collected any equipment and components he could find. The two heavily damaged DH9As were stripped of any salvageable components and the airframes burned.

There were now seven DH9As and two Bristol Fighters left on the ground. They were filled with petrol and the motor transport was put out of action. Then two more DH9As appeared overhead and they were signalled to return to Hinaidi. One misunderstood the signals and landed, bursting a tyre in the process. This delayed the departure whilst the tyre was changed so Manning got his men to tidy up the field.

Goodbyes were said to the faithful Levies who had decided they could look after themselves and the DH9As taxied out and took off in pairs. Last to leave was Manning’s Bristol. He took off from Sulaymaniya at 1235. It was just minutes more than 24 hours since he was given the first order and the operation had been successfully completed with no shots fired, no loss of life and no injury.

Although the official report gave adequate praise to Manning and his pilots and there seemed to be ample justification for the recommendation of an award none was recommended. Strangely, 21 months later, he was awarded the DSO for ‘distinguished services in Kurdistan from 15 February to 19 June, 1923’ a period not covering the airlift from Sulaymaniya .

Manning went on to other positions, including a short period as PA to Sir Hugh Trenchard, command of No 7 (Bomber) Sqn and Station Commander at RAF Hornchurch and Manston. He retired as Group Capt. In 1935. In 1939 he was recalled, serving mainly in India and Burma. He, was made a CBE in 1943 and retired as Air Commodore at the end of the war, going home to Australia. He died in 1957, aged 68.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

It was a busy airfield. Aeroplanes were being refuelled, loaded and at times were taking off at five minute intervals. Passengers waiting their turn were kept busy helping with the refuelling and tyre changing. Because of the gale, wing walkers were needed to help the aeroplanes taxi-ing. The wind continued to blow, strongly enough to demolish the windsock and its pole. The canvas continued to do its job by being stretched out on the ground and held down by rocks.

All this activity was attracting the attention of the townspeople and a crowd assembled alongside the airfield swelling to over two thousand. Manning had aircraft parked strategically so that their guns covered the excited crowd. The fifteen Levies were not finding it easy to control them. Manning tried to avoid spreading any impression of panic and deliberately slowed down the pace of the operation, stopping anyone from rushing about. By 0900 most of the civilians had left.

After the last passengers had gone the aircraft were loaded with bombs, detonators and guns. A wireless n.c.o. collected any equipment and components he could find. The two heavily damaged DH9As were stripped of any salvageable components and the airframes burned.

There were now seven DH9As and two Bristol Fighters left on the ground. They were filled with petrol and the motor transport was put out of action. Then two more DH9As appeared overhead and they were signalled to return to Hinaidi. One misunderstood the signals and landed, bursting a tyre in the process. This delayed the departure whilst the tyre was changed so Manning got his men to tidy up the field.

Goodbyes were said to the faithful Levies who had decided they could look after themselves and the DH9As taxied out and took off in pairs. Last to leave was Manning’s Bristol. He took off from Sulaymaniya at 1235. It was just minutes more than 24 hours since he was given the first order and the operation had been successfully completed with no shots fired, no loss of life and no injury.

Although the official report gave adequate praise to Manning and his pilots and there seemed to be ample justification for the recommendation of an award none was recommended. Strangely, 21 months later, he was awarded the DSO for ‘distinguished services in Kurdistan from 15 February to 19 June, 1923’ a period not covering the airlift from Sulaymaniya .

Manning went on to other positions, including a short period as PA to Sir Hugh Trenchard, command of No 7 (Bomber) Sqn and Station Commander at RAF Hornchurch and Manston. He retired as Group Capt. In 1935. In 1939 he was recalled, serving mainly in India and Burma. He, was made a CBE in 1943 and retired as Air Commodore at the end of the war, going home to Australia. He died in 1957, aged 68.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

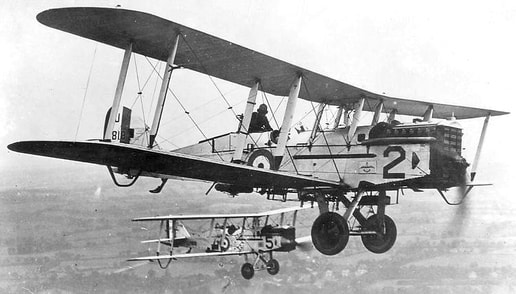

You might have noticed in the picture of the DH9A that it has a spare wheel fixed under the gunner’s cockpit. It seems to have been standard practice in the Middle East – they obviously had frequent wheel problems - and here’s another variation. Apologies if you’ve heard this story before, but it’s worth re-telling

A DH9A took off one day on a patrol and as it left the ground one of its wheels fell off. Now the crew can’t see the wheels from the cockpit – the lower wing is in the way. The observers on the ground realised that the pilot would get a nasty shock – and a nastier accident when he came home on touched down on one wheel and an axle stub. No wireless was fitted in the DH9A. How could they warn the pilot?

One bright lad knew. ‘Stick a spare wheel in the gunner’s cockpit so he knows what we’re trying to tell him and I’ll catch him up and let him know’. No one else had a better idea so the wheel was loaded and off he went.

As he left the ground (it must have been a rough airfield) one of his wheels fell off.

Eventually he found the one wheeled, two crew DH. He flew alongside pointing vigorously in the direction of his undercarriage and then to the spare wheel behind him. The bemused crew clearly didn’t get the message. The gunner stood up and, using the ‘shorthand’ semaphore they’d developed signalled ‘Bloody clever. Now put it back’.

As he left the ground (it must have been a rough airfield) one of his wheels fell off.

Eventually he found the one wheeled, two crew DH. He flew alongside pointing vigorously in the direction of his undercarriage and then to the spare wheel behind him. The bemused crew clearly didn’t get the message. The gunner stood up and, using the ‘shorthand’ semaphore they’d developed signalled ‘Bloody clever. Now put it back’.