Jean Batten 1909-1982 (Dec 2015)

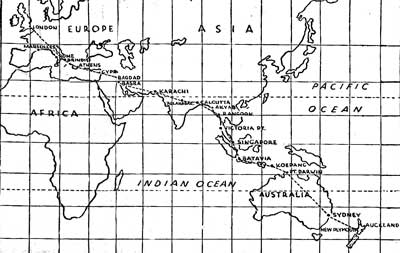

If you fly to New Zealand today you’ll arrive at the Jean Batten Terminal at Auckland Airport. Although it’s more usually referred to as the International Terminal Jean’s Vega Gull hangs from the ceiling commemorating her achievements. She gained fame with four record breaking flights, from England to Australia in May 1934, England to South America in November 1935, England to New Zealand in October 1936 and Australia to England in February 1937. After that, she faded from the public eye.

If you fly to New Zealand today you’ll arrive at the Jean Batten Terminal at Auckland Airport. Although it’s more usually referred to as the International Terminal Jean’s Vega Gull hangs from the ceiling commemorating her achievements. She gained fame with four record breaking flights, from England to Australia in May 1934, England to South America in November 1935, England to New Zealand in October 1936 and Australia to England in February 1937. After that, she faded from the public eye.

Jane Gardner Batten, always known as Jean, was the youngest child and only daughter of Fred and Ellen Batten. When the marriage failed and they separated the two boys lived with their father and the 11 year old Jean stayed with her mother. Ellen was a strong personality and determined feminist and raised her daughter in her own image. Jean studied ballet and the piano and seemed to be bound for a career in music. But, at 19 years of age, she abandoned these plans when she became inspired by a talk given by Charles Kingsford Smith, the Australian aviator who had made the first trans-Pacific flight. She announced that she was going to be a pilot and even said that she was going to be the first person to fly from England to New Zealand.

The discouragement that came from her father that flying was dangerous and ‘not a suitable career for a girl’ only strengthened Ellen’s resolve and support for her daughter. The family had little money so Ellen sold Jean’s piano and bought two tickets for the voyage to England. Fred was told that Jean was going to study music and he sent her what he could, an allowance of £2 per week. Ellen and Jean rented a cheap room and took the tube to Stag Lane, home of the London Aeroplane Club.

The discouragement that came from her father that flying was dangerous and ‘not a suitable career for a girl’ only strengthened Ellen’s resolve and support for her daughter. The family had little money so Ellen sold Jean’s piano and bought two tickets for the voyage to England. Fred was told that Jean was going to study music and he sent her what he could, an allowance of £2 per week. Ellen and Jean rented a cheap room and took the tube to Stag Lane, home of the London Aeroplane Club.

Although Jean attracted attention as a beautiful young new member she resisted all efforts to involve her in the social life of the club and was never seen in the bar. She turned up promptly for her lessons and left immediately afterwards. No-one knew where she lived. Any mail had to be addressed, even by the family, to Thomas Cook, London.

She was a diligent pupil but a slow learner. Finally, she gained her licence in December 1930, just six months after another club member, Amy Johnson, had shot to fame with her solo flight to Australia. Jean hoped to get an aeroplane for a flight to New Zealand but her plans abruptly fell apart. Her father had learned of his daughter’s deception and stopped her allowance. Ellen and Jean used the last of their money to sail home.

She was a diligent pupil but a slow learner. Finally, she gained her licence in December 1930, just six months after another club member, Amy Johnson, had shot to fame with her solo flight to Australia. Jean hoped to get an aeroplane for a flight to New Zealand but her plans abruptly fell apart. Her father had learned of his daughter’s deception and stopped her allowance. Ellen and Jean used the last of their money to sail home.

On the voyage, the ship was joined in Bombay by Flt. Lt. Fred Truman, a serving RAF officer who was going home to New Zealand on leave. Jean usually avoided any involvement with others but a friendship developed which continued during Fred’s leave. Meanwhile, father Fred had forgiven Jean and, in the interests of her safety, even paid for her to continue flying and learn navigation.

Soon, she was back on the boat to England. Where she got the money for the journey was not clear at the time but it later emerged that it came from her brother John. He had been working in England as an actor and was concerned that Jean would try to get her father, who had little financial reserves, to pay her fare. For a short while, she lived with John but soon there was a blazing row and Jean packed her bags and left. She was never to speak to her brother again.

Jean’s aim was to gain her B Licence and qualify as a professional pilot. This required her to complete 100 hours flying, a challenge for the apparently impecunious Jean. The source of the money which paid for this was discovered many years later. Jean had nurtured her friendship with Fred Truman. When he completed his RAF service he was paid a gratuity of £500, all of which he willingly lent to Jean. Now qualified, she completed her preparation with courses in engineering. All she needed was an aeroplane.

Soon, she was back on the boat to England. Where she got the money for the journey was not clear at the time but it later emerged that it came from her brother John. He had been working in England as an actor and was concerned that Jean would try to get her father, who had little financial reserves, to pay her fare. For a short while, she lived with John but soon there was a blazing row and Jean packed her bags and left. She was never to speak to her brother again.

Jean’s aim was to gain her B Licence and qualify as a professional pilot. This required her to complete 100 hours flying, a challenge for the apparently impecunious Jean. The source of the money which paid for this was discovered many years later. Jean had nurtured her friendship with Fred Truman. When he completed his RAF service he was paid a gratuity of £500, all of which he willingly lent to Jean. Now qualified, she completed her preparation with courses in engineering. All she needed was an aeroplane.

One of Jean’s most persistent admirers was Victor Dorée, son of a wealthy linen merchant. He already had his own DH Moth which he allowed Jean to use as she was running out of money. Victor’s mother was persuaded to buy a second-hand Moth, to be jointly owned by Jean and Victor who would also share in any profits from Jean’s planned flight to Australia. This Moth had a pedigree, having once been owned by the Prince of Wales, but after four other owners and two crashes it needed some work. All this, plus the fitting of a long-range fuel tank and other modifications came out of Victor’s wallet.

Jean’s long strips of carefully prepared maps had extensive notes of all aerodromes, lighthouses and checkpoints for the whole route but her main navigation aids were the basic watch and compass. To help to check drift, she had a number of lines painted at different angles on the lower wing trailing edges and a few small bags which, when dropped on the sea, broke open to scatter reflective aluminium particles. She took no parachute. Her log book recorded just 130 hours flying.

Although Victor invited the press to see her off only one reporter came to Stag Lane on 8 April 1933. The flight went well and her navigation was precise. She refuelled at Naples, Athens and Aleppo. An hour after leaving for Baghdad, she flew into the first of a series of sandstorms. Her only ‘blind-flying’ instrument was a bubble in a curved tube which really indicated only slipping and skidding. In the turbulence, the Moth fell into a spin. Somehow, she recovered when close to the desert and managed to land the Moth. For an hour, she had to hang on to a strut with a coat over her head as protection from the stinging sand. When the storm abated, she swung the prop and took off again. But the delay meant that she could not reach Baghdad before the sun set. Seeing a camel track in the last of the light she landed again, picketed the Moth, covered the engine, spread out the cockpit cushions and fell asleep.

She awoke in the morning surrounded by eight bearded Arabs, curiously inspecting the aeroplane. She established friendly relations by offering them cigarettes and they watched her swinging the propeller. She took off hurriedly without fastening her seat belt and an hour later was eating breakfast in the Officers’ Mess at RAF Hinaidi.

The flight continued down the Persian Gulf towards Karachi. With just half an hour to go she was overtaken by another sandstorm which swept her over the ground at what seemed a tremendous speed. Noticing a village she thought she should turn into the wind and land in one of the small fields. With considerable skill, she hurdled the irrigation banks and dropped the Moth into the largest field she could see. The landing run was short, but ended in a patch of damp ground and the propeller tipped into the mud and split. The villagers, who had never seen an aeroplane before, helped her to drag the Moth to dry ground and Jean set off by horse, camel and ancient lorry to get a new prop from the de Havilland agent in Karachi.

Although Victor invited the press to see her off only one reporter came to Stag Lane on 8 April 1933. The flight went well and her navigation was precise. She refuelled at Naples, Athens and Aleppo. An hour after leaving for Baghdad, she flew into the first of a series of sandstorms. Her only ‘blind-flying’ instrument was a bubble in a curved tube which really indicated only slipping and skidding. In the turbulence, the Moth fell into a spin. Somehow, she recovered when close to the desert and managed to land the Moth. For an hour, she had to hang on to a strut with a coat over her head as protection from the stinging sand. When the storm abated, she swung the prop and took off again. But the delay meant that she could not reach Baghdad before the sun set. Seeing a camel track in the last of the light she landed again, picketed the Moth, covered the engine, spread out the cockpit cushions and fell asleep.

She awoke in the morning surrounded by eight bearded Arabs, curiously inspecting the aeroplane. She established friendly relations by offering them cigarettes and they watched her swinging the propeller. She took off hurriedly without fastening her seat belt and an hour later was eating breakfast in the Officers’ Mess at RAF Hinaidi.

The flight continued down the Persian Gulf towards Karachi. With just half an hour to go she was overtaken by another sandstorm which swept her over the ground at what seemed a tremendous speed. Noticing a village she thought she should turn into the wind and land in one of the small fields. With considerable skill, she hurdled the irrigation banks and dropped the Moth into the largest field she could see. The landing run was short, but ended in a patch of damp ground and the propeller tipped into the mud and split. The villagers, who had never seen an aeroplane before, helped her to drag the Moth to dry ground and Jean set off by horse, camel and ancient lorry to get a new prop from the de Havilland agent in Karachi.

Two hectic days later, she was flying again and Drigh Road airfield was in sight. She could still beat Amy Johnson’s record. Her optimism was shattered when, with an alarming clatter, a con-rod broke and the engine shuddered into silence.

Options for a forced landing were severely limited in the rough ground below and the road she was following seemed the only possibility. As she floated down to a clear stretch she saw that the narrow road was bordered by a series of marker stones, too high for the wingtips to clear. The Moth swung sharply and somersaulted. Jean crawled out of the wreckage, miraculously unhurt, but her record attempt, and Victor’s Moth, were shattered.

Two hectic days later, she was flying again and Drigh Road airfield was in sight. She could still beat Amy Johnson’s record. Her optimism was shattered when, with an alarming clatter, a con-rod broke and the engine shuddered into silence.

Options for a forced landing were severely limited in the rough ground below and the road she was following seemed the only possibility. As she floated down to a clear stretch she saw that the narrow road was bordered by a series of marker stones, too high for the wingtips to clear. The Moth swung sharply and somersaulted. Jean crawled out of the wreckage, miraculously unhurt, but her record attempt, and Victor’s Moth, were shattered.

Back in England press interest had been aroused by comparing her progress with Amy Johnson’s. The delays caused by her forced landings brought her to wider notice and Lord Wakefield, owner of Castrol Oil, offered to pay for Jean’s – and the wrecked Moth’s – return to England. It was just another act of generosity to flyers as part of the company’s PR. She was welcomed home by Victor who wanted to marry her. But his father had died and the death duties ate into the family’s finances. Still driven by her desire to fly to Australia, Jean could see no more help coming from Victor so she dropped him.

Now penniless and with no job, Jean worked hard on the Castrol connection and eventually was given £400. In anticipation of this she had already persuaded Shell to sponsor her with fuel. She found an old Gipsy Moth for £260 which she took to Brooklands.

There she met a weekend flyer, Edward Walter, who was a stockbroker with his own Moth. He helped Jean and, within weeks, they were engaged to be married, although Jean insisted that this should be kept secret.

There she met a weekend flyer, Edward Walter, who was a stockbroker with his own Moth. He helped Jean and, within weeks, they were engaged to be married, although Jean insisted that this should be kept secret.

Again, all her preparations were meticulous and, just over a year since her previous departure, she took off for Australia on 21 April 1934. Landing in heavy rain at Marseilles she found the airfield surface so wet that she took on a reduced amount of fuel to ensure a safer take-off. Although the airfield authorities warned her against flying to Rome in foul weather against a strong headwind she insisted, so they made her sign an indemnity accepting full responsibility. The weather got worse and she scudded along at cloud base with the surface barely visible. The planned route crossed the mountains of Corsica but they were covered in storm clouds. Jean turned south to fly round the coast of the island. Although the 130 mile diversion and the 40 mph headwind added time and used precious fuel she pressed on into the increasing darkness. She pumped the remaining fuel into the gravity tank, even holding up the nose near the stall to suck up the last drops.

Before the blurred lights of the Italian coast came into view, the fuel gauge was reading zero. Amazingly, she was exactly on course and she flew on searching in vain for the lights of the airfield. The staff had long since given up waiting and had gone home. She was over the city when the engine gave its final cough. Gliding down towards the streets she noticed a dark unlit patch ahead. At the last second her hand torch picked up a line of trees. She hauled up the nose, the Moth stalled and fell to the ground, pitching forward and breaking the prop. Jean climbed out with a black eye and badly cut lower lip. She was staggered to find that that she was in a radio station and somehow had missed the 650 ft masts and their invisible supporting wires.

The helpful Italians looked after Jean and took the Moth to a hangar at the airport. They were able to repair the undercarriage and fuselage damage but the lower wings were a mess. Jean found an old dismantled engineless Moth in a corner, tracked down its owner and struck a deal to borrow the lower wings. She cabled Ted Walker to take the prop from his Moth and send it to Rome. Ten days after the crash, she flew back to London.

New wings had been ordered but they were not ready. Jean persuaded Ted to take the lower wings from his Moth and have them fitted to hers. The Brooklands engineers worked frantically and within just two days, anxious to beat the onset of the monsoon, Jean took off, yet again, for Australia.

Before the blurred lights of the Italian coast came into view, the fuel gauge was reading zero. Amazingly, she was exactly on course and she flew on searching in vain for the lights of the airfield. The staff had long since given up waiting and had gone home. She was over the city when the engine gave its final cough. Gliding down towards the streets she noticed a dark unlit patch ahead. At the last second her hand torch picked up a line of trees. She hauled up the nose, the Moth stalled and fell to the ground, pitching forward and breaking the prop. Jean climbed out with a black eye and badly cut lower lip. She was staggered to find that that she was in a radio station and somehow had missed the 650 ft masts and their invisible supporting wires.

The helpful Italians looked after Jean and took the Moth to a hangar at the airport. They were able to repair the undercarriage and fuselage damage but the lower wings were a mess. Jean found an old dismantled engineless Moth in a corner, tracked down its owner and struck a deal to borrow the lower wings. She cabled Ted Walker to take the prop from his Moth and send it to Rome. Ten days after the crash, she flew back to London.

New wings had been ordered but they were not ready. Jean persuaded Ted to take the lower wings from his Moth and have them fitted to hers. The Brooklands engineers worked frantically and within just two days, anxious to beat the onset of the monsoon, Jean took off, yet again, for Australia.

A newspaper headline had predicted ‘Third Time Lucky’ and so it seemed. The flight went according to plan and on the tenth day she left Calcutta hoping to be treated kindly by the Intertropical Convergence Zone, that line of almost incessant thunderstorms that circles the equator. She wasn’t. It was like flying through a waterfall, keeping just above the sea to avoid being sucked into the black cloud. It was so dark that she needed her torch to be able to read her instruments. Yet her navigation was faultless and she found the landing strips at Victoria Point and Alor Star before making it to Singapore.

The 500 mile crossing of the Timor Sea was estimated to take six hours. A stronger than forecast headwind prolonged the agony of waiting for the sight of land. It was seven and a half hours, with most of her fuel gone, before she sighted land. She landed at Darwin 14 days, 22 hours and 30 minutes after leaving England. Amy Johnson’s record had been beaten by over four days. Lord Wakefield told his Australian manager to take the company Hawk Moth to Darwin and accompany Jean to Sydney where she arrived in triumph and a blizzard of telegrams. She made the first of many speeches and began a round of public engagements.

She was world famous, feted wherever she went and the recipient of many awards, not least of which was the £1000 bonus from Lord Wakefield. But the burning desire to fly to New Zealand was still unfulfilled

She was world famous, feted wherever she went and the recipient of many awards, not least of which was the £1000 bonus from Lord Wakefield. But the burning desire to fly to New Zealand was still unfulfilled

The welcome accorded to Jean on her arrival in Australia was astonishing. Of all the England-Australia fliers she was certainly the prettiest but by no means the first. Fifteen years previously, in 1919, the pioneers were Ross and Keith Smith in a Vickers Vimy with their mechanics James Bennet and Wally Shiers. She wasn’t even the first woman. Amy Johnson claimed that honour in 1930, and in 1932 a German pilot, Elly Beinhorn, landed in Darwin after a leisurely flying holiday which took 110 days. The great Charles Kingsford-Smith made the flight in 1930 and the well-trodden route had been completed more than thirty times. But Jean made a significant impact and gained an army of female fans. After an exhausting round of receptions and speeches she was glad to escape by taking ship (with her Moth) to New Zealand.

Then it all began again. She was hailed by the Kiwis as ‘our Jean’. For six weeks she gave her repetitive talk across the country, boosted by the arrival from England of her mother, Ellen. She was greatly admired by the crowds, but others saw a complex character. Basically naïve and unworldly she avoided closer contact with people whilst at the same time exuding confidence and arrogance. She left many saying ‘Who does she think she is?’

Jean went back to Australia with her mother and planned to write a book before flying back to England. Although it was too late for her to enter the MacRobertson race she was hired to give a radio commentary. She was there when Scott and Campbell Black landed their Comet at Laverton and later she flew to Sydney in the second placed DC-2. At the airport she met Beverley Shepherd, a young Australian who was training to be an airline pilot. Jean fell in love with him and it wasn’t long before she returned her engagement ring to Edward Walter in England. His bitter reply enclosed a bill for all the aircraft parts she had taken from his Moth. Her book, Solo Flight, was published to a lukewarm reception.

Her return flight to England was kept secret until the last minute so few people saw her off. Beverley was there, of course, holding her wing tip as she taxied out. She hoped to set a time faster than her flight to Australia. Trouble struck quite soon. She left Darwin for the six hour flight over the Timor Sea in a dense orange haze caused by dust storms raised by the strong SE wind. She climbed to 6000 ft, unusually but providentially high for her. Three hours into the flight, the engine coughed. A second cough was followed by another, then - the engine stopped.

Jean checked everything. The gravity tank was full and all she could do was to pump the throttle. There was no reaction and the Moth glided silently down into the orange cloud. Without a parachute or life-raft the end seemed inevitable. The throttle was open wide in case whatever blockage in the fuel lines might clear. The sea came in sight. Jean loosened her shoelaces, pumped the throttle yet again and prayed. At almost the last second, the engine burst into life.

Skimming the sea, she persuaded the Moth to climb to a safer height. There was more spluttering from the engine but it kept going till she reached Kupang. A thorough cleaning of the filters and carburettor jets wasn’t enough to eliminate the problem and she suffered occasional rough running and cut-outs for the rest of the journey. Over Italy, she had magneto trouble and had to return to Foggia. A puncture and a forced landing in France caused further delays and she arrived in Croydon two and a half days after her target.

Exhausted and depressed, she still had to rise to the publicity bandwagon, sponsored by newspapers and the aviation community. She was awarded the Challenge Trophy by the Women’s International Association of Aeronautics in America and there was talk of film rights and another book.

Her sights were now set on another record flight and she chose the South Atlantic, yet to be flown solo by a woman. Looking for an aeroplane more suitable than the slow Moth she chose a new and expensive Percival Gull 6, powered by a 200 hp DH Gipsy Six engine. She took delivery on 15 September, 1935, her 26th birthday.

Then it all began again. She was hailed by the Kiwis as ‘our Jean’. For six weeks she gave her repetitive talk across the country, boosted by the arrival from England of her mother, Ellen. She was greatly admired by the crowds, but others saw a complex character. Basically naïve and unworldly she avoided closer contact with people whilst at the same time exuding confidence and arrogance. She left many saying ‘Who does she think she is?’

Jean went back to Australia with her mother and planned to write a book before flying back to England. Although it was too late for her to enter the MacRobertson race she was hired to give a radio commentary. She was there when Scott and Campbell Black landed their Comet at Laverton and later she flew to Sydney in the second placed DC-2. At the airport she met Beverley Shepherd, a young Australian who was training to be an airline pilot. Jean fell in love with him and it wasn’t long before she returned her engagement ring to Edward Walter in England. His bitter reply enclosed a bill for all the aircraft parts she had taken from his Moth. Her book, Solo Flight, was published to a lukewarm reception.

Her return flight to England was kept secret until the last minute so few people saw her off. Beverley was there, of course, holding her wing tip as she taxied out. She hoped to set a time faster than her flight to Australia. Trouble struck quite soon. She left Darwin for the six hour flight over the Timor Sea in a dense orange haze caused by dust storms raised by the strong SE wind. She climbed to 6000 ft, unusually but providentially high for her. Three hours into the flight, the engine coughed. A second cough was followed by another, then - the engine stopped.

Jean checked everything. The gravity tank was full and all she could do was to pump the throttle. There was no reaction and the Moth glided silently down into the orange cloud. Without a parachute or life-raft the end seemed inevitable. The throttle was open wide in case whatever blockage in the fuel lines might clear. The sea came in sight. Jean loosened her shoelaces, pumped the throttle yet again and prayed. At almost the last second, the engine burst into life.

Skimming the sea, she persuaded the Moth to climb to a safer height. There was more spluttering from the engine but it kept going till she reached Kupang. A thorough cleaning of the filters and carburettor jets wasn’t enough to eliminate the problem and she suffered occasional rough running and cut-outs for the rest of the journey. Over Italy, she had magneto trouble and had to return to Foggia. A puncture and a forced landing in France caused further delays and she arrived in Croydon two and a half days after her target.

Exhausted and depressed, she still had to rise to the publicity bandwagon, sponsored by newspapers and the aviation community. She was awarded the Challenge Trophy by the Women’s International Association of Aeronautics in America and there was talk of film rights and another book.

Her sights were now set on another record flight and she chose the South Atlantic, yet to be flown solo by a woman. Looking for an aeroplane more suitable than the slow Moth she chose a new and expensive Percival Gull 6, powered by a 200 hp DH Gipsy Six engine. She took delivery on 15 September, 1935, her 26th birthday.

Whilst arranging the flight, she went to Shell-Mex House to confirm her fuel supplies. There she met a handsome young man with a slight limp. He gave her a photograph of Cape San Roque, her planned landfall in Brazil. On the back was written ‘Good luck from Douglas’. ‘Douglas who?’ she asked. ‘Bader’ was the reply.

She intended to fly to Dakar in French Senegal before tackling the 1900 miles over-sea leg. On the day she was leaving she was given a letter from the French aviation authorities forbidding any flight across the Sahara without a radio. She tore it up. Despite a bad forecast she took off on 11 November 1935 for Casablanca, crossing France at 150 mph at 14,000 ft. For the Atlantic crossing she was loaded with every drop on fuel she could carry. The long take-off from Senegal was made at 4.45 am with only the lights of a car at the upwind boundary to guide her. She looked forward to a flight of 13 hours with no landmarks to check her navigation. She had calculated that an error of just 1° in her track would make her 34 miles off course at her landfall – and the forecast was for a deep depression in the convergence zone, right on her path.

She flew low, only 600 ft above the sea so as to keep a careful check on any drift. In the wall of cloud and heavy rain she encountered she was down to 50 ft to keep the water in sight. Then she noticed, with some panic, that the compass was swinging. She concentrated on the turn indicator to fly straight and level even though the compass needle had turned 180°. When the Gull burst out into bright sunshine the compass swung back. She learned later that the Air France mail pilots who flew this route had often met this phenomenon in electrical storms near the Equator.

Now she was affected by increasingly strong south-easterly winds which needed an 8° course correction. 9 hours after take-off, with 600 miles still to go she saw a ship ahead, presumably heading for Dakar. If so, its wake told her she was dead on course. She celebrated by flying low past the ship, waving at the crew. 12½ hours out from Africa, she reached the coast of Brazil and, just half a mile north was the little palm-covered promontory which she recognised from Bader’s photograph. It was a triumph of navigation.

She intended to fly to Dakar in French Senegal before tackling the 1900 miles over-sea leg. On the day she was leaving she was given a letter from the French aviation authorities forbidding any flight across the Sahara without a radio. She tore it up. Despite a bad forecast she took off on 11 November 1935 for Casablanca, crossing France at 150 mph at 14,000 ft. For the Atlantic crossing she was loaded with every drop on fuel she could carry. The long take-off from Senegal was made at 4.45 am with only the lights of a car at the upwind boundary to guide her. She looked forward to a flight of 13 hours with no landmarks to check her navigation. She had calculated that an error of just 1° in her track would make her 34 miles off course at her landfall – and the forecast was for a deep depression in the convergence zone, right on her path.

She flew low, only 600 ft above the sea so as to keep a careful check on any drift. In the wall of cloud and heavy rain she encountered she was down to 50 ft to keep the water in sight. Then she noticed, with some panic, that the compass was swinging. She concentrated on the turn indicator to fly straight and level even though the compass needle had turned 180°. When the Gull burst out into bright sunshine the compass swung back. She learned later that the Air France mail pilots who flew this route had often met this phenomenon in electrical storms near the Equator.

Now she was affected by increasingly strong south-easterly winds which needed an 8° course correction. 9 hours after take-off, with 600 miles still to go she saw a ship ahead, presumably heading for Dakar. If so, its wake told her she was dead on course. She celebrated by flying low past the ship, waving at the crew. 12½ hours out from Africa, she reached the coast of Brazil and, just half a mile north was the little palm-covered promontory which she recognised from Bader’s photograph. It was a triumph of navigation.

It was, naturally, an all-time record and she was in the papers and the radio news again. Just one more leg, a mere 10 hour flight, and she would be welcomed in Rio. But she didn’t arrive and night fell. At dawn, a squadron of the Brazilian air force was launched to find her. They discovered the Gull on a beach 175 miles from Rio. When she had switched to her last tank she found it to be empty. A loose connection had drained the tank. The forced landing in soft sand had bent the propeller. Repairs were quickly carried out and the Brazilian Wacos escorted her into Rio to a riotous reception.

She was feted in Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. Among many offers for business promotions the most intriguing came from Charles Lindbergh. He invited her to fly to the States for a coast-to-coast lecture tour. It was much more exciting than the offer of the Royal Mail Line to take her and the Gull back to England for Christmas. Casting a light on the extra-ordinary relationship between the two women, Jean felt she had to cable her mother for permission to go to America. Ellen said ‘No’ and Jean dutifully boarded the ship for England.

She was feted in Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. Among many offers for business promotions the most intriguing came from Charles Lindbergh. He invited her to fly to the States for a coast-to-coast lecture tour. It was much more exciting than the offer of the Royal Mail Line to take her and the Gull back to England for Christmas. Casting a light on the extra-ordinary relationship between the two women, Jean felt she had to cable her mother for permission to go to America. Ellen said ‘No’ and Jean dutifully boarded the ship for England.

The awards began to flood in: the Royal Aero Club’s Britannia Trophy, the Gold Medal of the French Academy for Sports, the Harmon Trophy (jointly with Amelia Earhart for the first California – Hawaii solo flight), the Spirit of Aviation bronze figure from the Brazilian Air Force, the Challenge Trophy by the Women’s International Association of Aeronautics in America (for the second time) and she was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (the award already held by Amy Johnson).

All the acclaim and the requests for speeches became quite stressful for Jean and as soon as she could she retreated to the house in Hatfield where she and Ellen were living in seclusion. To the outside world, their address, as always, was Thomas Cook, London. She devoted her time on the preparations for the long-promised flight to New Zealand. The plans were kept secret until the last minute but the press were at Lympne in force to see her take off in the Gull before dawn on 5 October 1936.

Although the main object of the venture was to be the first to fly solo to New Zealand, Jean was determined to beat the solo record to Australia, six days and 21 hours, set by Jimmy Broadbent.

Although the main object of the venture was to be the first to fly solo to New Zealand, Jean was determined to beat the solo record to Australia, six days and 21 hours, set by Jimmy Broadbent.

She drove herself hard, navigating along her 72 feet long concertina of strip maps. Cruising at 14,000 ft she reached Karachi in just 2 ½ days. The inter-tropical front caused problems again. Forced down to sea level in very poor visibility she was following the coast of Burma when she realised she was being led into a narrow inlet. Suddenly, her way ahead was blocked by steep hills and there was no room to turn, nor could she risk climbing into cloud. Instinctively she hauled up the nose, closed the throttle, kicked on full rudder and did a stall turn.

It allowed her to escape to the sea where she climbed to a safe height and relied on the instruments and compass.

It allowed her to escape to the sea where she climbed to a safe height and relied on the instruments and compass.

The torrents of heavy rain continued and, despite the closed cockpit, she was soaked. Then she noticed that the wings were turning pink. The silver paint was being rain-blasted away and the red undercoat was showing. At Penang, she made temporary repairs to the worn fabric with tape from her first aid kit. The RAF at Singapore applied better repairs and she flew on through the night and most of the next day to Kupang, ready for the Timor Sea crossing. But on landing the tailwheel was punctured. Her agent drove into Kupang to buy enough sponges to stuff into the tyre. The delay meant that it was too late to reach Darwin in daylight and Jean was able to snatch a short rest. She had slept only seven hours in the past five days.

After a before-dawn take off she reached Darwin four hours later. It wasn’t over yet. On her first approach, the throttle jammed open and she had to overshoot. For the next attempt to land she switched off the engine but still came in too fast. When she put on the brakes a hydraulic leak meant that only one worked and the Gull spun round in a ground loop. Luckily it wasn’t broken – but the record was. She had beaten Jimmy Broadbent by a full 24 hours. Her time was to remain unbeaten for 44 years.

The 2200 miles to reach Sydney took another two days. At the brief overnight stop at Longville the crowds were waiting, many having driven great distances. Jean ignored them all. She refused to give any newspaper or radio interviews and disappeared into a hotel room. It was different at Sydney. In her crisp white flying suit she was swept along by the mass of people to her hotel where 1700 telegrams waited for her.

Two days were spent waiting for the weather to improve. Days filled by astounding offers, one for £600 for a 15 minute radio broadcast (at the time the average annual salary was about £300). The newspaper baron, Frank Packer, offered a seriously tempting £5000 for a lecture tour - provided she didn’t fly the Tasman. Others tried to stop her. The Tasman had a fearsome reputation and had claimed the lives of other fliers. The Civil Aviation Department banned the flight on the grounds that her take-off weight would exceed the Gull’s Certificate of Airworthiness limit. Jean demanded an interview with a Federal Minister and produced a British special permit allowing her to take off with an overload of 1000 lbs. In two crowded days, Jean accepted several deals, rumoured to total at least £20,000.

After a before-dawn take off she reached Darwin four hours later. It wasn’t over yet. On her first approach, the throttle jammed open and she had to overshoot. For the next attempt to land she switched off the engine but still came in too fast. When she put on the brakes a hydraulic leak meant that only one worked and the Gull spun round in a ground loop. Luckily it wasn’t broken – but the record was. She had beaten Jimmy Broadbent by a full 24 hours. Her time was to remain unbeaten for 44 years.

The 2200 miles to reach Sydney took another two days. At the brief overnight stop at Longville the crowds were waiting, many having driven great distances. Jean ignored them all. She refused to give any newspaper or radio interviews and disappeared into a hotel room. It was different at Sydney. In her crisp white flying suit she was swept along by the mass of people to her hotel where 1700 telegrams waited for her.

Two days were spent waiting for the weather to improve. Days filled by astounding offers, one for £600 for a 15 minute radio broadcast (at the time the average annual salary was about £300). The newspaper baron, Frank Packer, offered a seriously tempting £5000 for a lecture tour - provided she didn’t fly the Tasman. Others tried to stop her. The Tasman had a fearsome reputation and had claimed the lives of other fliers. The Civil Aviation Department banned the flight on the grounds that her take-off weight would exceed the Gull’s Certificate of Airworthiness limit. Jean demanded an interview with a Federal Minister and produced a British special permit allowing her to take off with an overload of 1000 lbs. In two crowded days, Jean accepted several deals, rumoured to total at least £20,000.

The reception at Auckland exceeded all previous celebrations and Jean was overwhelmed. Constant demands for talks and pressure of new media contracts took their toll and Jean frequently showed signs of strain. One persistent request came from Fred Truman, whose £500 gratuity had financed her flying training. Fred had been badly hit by the economic depression and had cabled Jean in London asking for the return of his loan. She had told him he had to ‘wait his turn’. Now he wrote letters and phoned her hotel with no result. Finally, he went to see her father and told him the whole story. Fred Batten was horrified and insisted on a meeting at Jean’s hotel. She arrived late, thrust a cheque into Fred Truman’s hand and walked off without a word. It was for £250. Disgusted, Fred gave up

Jean was becoming increasingly stressed, even said she was tired of flying and opted to travel to her many engagements by train. Finally, a doctor was called and diagnosed her to be close to a nervous collapse. He recommended cancelling the lecture tour. She spent a few weeks convalescing then quietly sailed to Sydney. She wanted to see Beverly Shepherd again, now wearing his smart airline pilot’s uniform. Avoiding publicity, they escaped on a tour of the country in his Puss Moth and planned their future life together. However, Jean wanted to go back to New Zealand in time to meet her mother who was sailing from England. They planned to spend Christmas ‘at home’ and did so by disappearing from public view.

Beverly was urging her to return to Australia and in February 1937 she booked a passage for herself, Ellen and the Gull. As soon as they docked Jean hurried to Mascot airfield where Beverley was due on a flight from Brisbane. The Stinson airliner failed to arrive. The next morning Jean was one of the first searchers to take off. Others abandoned the search after five days but Jean went on alone. On the ninth day, the wreckage of the Stinson was found on the side of a mountain. Only two passengers had survived and Jean’s dreams were shattered. She and Ellen once more retreated into isolation.

The spur for her emergence was probably the news that Jimmy Broadbent was preparing to attack her record for the England-Australia flight. She prepared the Gull for the flight to England intending to pass Jimmy on the way. Ellen sailed to England and Jean took off on 14 October. She did more night flying than before and made excellent progress although she was soon suffering badly from lack of sleep. At Karachi she was reported to be ‘in a semi-coma’ but, after just four hours sleep, she flew on. Approaching Rome the weather was too bad to see the airfield so she flew back to Naples. Even though all other planes were grounded Jean found her way in, so exhausted that she had to be lifted out of the cockpit. She left at dawn and fought through more storms over France to reach Lympne five days, 19¼ hours after leaving Australia. She had beaten the record held by Jimmy Broadbent and now held the record for both directions. (Broadbent’s effort had ended in a forced landing near Baghdad).

She enjoyed another ecstatic welcome with awards and receptions (including one in Buckingham Palace). Then she and Ellen moved to a quiet house in St Albans so that she could write her autobiography. In 1938 she flew about Europe in the Gull giving a series of talks about her flights. In 1939, she was hired by the British Council, this time to talk on the British Empire. She flew home from Sweden seven days before war was declared.

She enjoyed another ecstatic welcome with awards and receptions (including one in Buckingham Palace). Then she and Ellen moved to a quiet house in St Albans so that she could write her autobiography. In 1938 she flew about Europe in the Gull giving a series of talks about her flights. In 1939, she was hired by the British Council, this time to talk on the British Empire. She flew home from Sweden seven days before war was declared.

Immediately she wrote to the government offering her, and the Gull’s service. They suggested there might be a place for her in an organisation being formed to deliver aeroplanes from factories. But Pauline Gower, who was setting up the women’s section of the ATA, was not interested. She had had sufficient contact with Jean to know how demanding and uncooperative she was with other pilots. Jean claimed that she had failed the medical because of short-sightedness, but others who were less fit were recruited. Her Gull, however, was requisitioned and spent the war in camouflage.

For a capable pilot with 2,600 hours in her logbook she had an odd wartime career. First, she became a driver with the Anglo-French Ambulance Corps but that was disbanded in May 1940 when France was overrun. Next, she went to work at the Royal Ordnance Factory in Poole as an inspector, checking parts of the 20mm cannons being manufactured there. In 1943, the National Savings Committee poached her as a motivational speaker. She spoke to audiences in factories, dockyards and town halls, to crowds in Trafalgar Square and even to a group of Welsh miners underground, successfully raising money for the war effort.

At the end of the war Ellen wanted to live in a warmer climate. They moved to Jamaica and had a house built on the north coast. Their near-neighbours included Ian Fleming and Noel Coward. Although there was a thriving ex-pat social round the Battens avoided being drawn into it as much as possible. After six years, they left the island and the neighbours found they had gone only when the house appeared on the market.

In 1953, they returned to England to collect a new car and set off on a rootless tour of Europe which went on for seven years. Although Jean recalls this period as a time when she and her mother were usually ‘helpless with laughter’ any acquaintances they met did not see this. It was a strange pairing of dominance and devotion and Jean seemed, inwardly, to be deeply unhappy in a life without purpose.

Eventually, they settled in a small fishing village in Spain. After six quiet years they were driven out by the hotel building boom for the expanding tourist trade. For a time, they toured again in North Africa and finally, in 1966, rented a small apartment in Tenerife. They had not been there long when Ellen died, just short of her 90th birthday.

Jean was now alone and engulfed in grief at her mother’s death. She bought a tiny flat and for three long years, avoided all contact with others. The death of her father in 1967 made little impact. Then, in 1969, she was invited to spend a week at the Waldorf Hotel in London to attend the start of an air race from England to Australia commemorating the 50th anniversary of Ross and Keith Smith’s 1919 flight in the Vickers Vimy. She used the money her father had left her to pay for a face lift in Harley Street. She disguised her age - she was now 60 - by having her hair dyed black and dressing in fashionable miniskirts. She stood with Sir Francis Chichester as he flagged off the competitors and noted, with some pleasure, that none beat her still standing solo record time to Darwin.

At the end of the war Ellen wanted to live in a warmer climate. They moved to Jamaica and had a house built on the north coast. Their near-neighbours included Ian Fleming and Noel Coward. Although there was a thriving ex-pat social round the Battens avoided being drawn into it as much as possible. After six years, they left the island and the neighbours found they had gone only when the house appeared on the market.

In 1953, they returned to England to collect a new car and set off on a rootless tour of Europe which went on for seven years. Although Jean recalls this period as a time when she and her mother were usually ‘helpless with laughter’ any acquaintances they met did not see this. It was a strange pairing of dominance and devotion and Jean seemed, inwardly, to be deeply unhappy in a life without purpose.

Eventually, they settled in a small fishing village in Spain. After six quiet years they were driven out by the hotel building boom for the expanding tourist trade. For a time, they toured again in North Africa and finally, in 1966, rented a small apartment in Tenerife. They had not been there long when Ellen died, just short of her 90th birthday.

Jean was now alone and engulfed in grief at her mother’s death. She bought a tiny flat and for three long years, avoided all contact with others. The death of her father in 1967 made little impact. Then, in 1969, she was invited to spend a week at the Waldorf Hotel in London to attend the start of an air race from England to Australia commemorating the 50th anniversary of Ross and Keith Smith’s 1919 flight in the Vickers Vimy. She used the money her father had left her to pay for a face lift in Harley Street. She disguised her age - she was now 60 - by having her hair dyed black and dressing in fashionable miniskirts. She stood with Sir Francis Chichester as he flagged off the competitors and noted, with some pleasure, that none beat her still standing solo record time to Darwin.

She was interviewed on radio and television and sparkled as the guest of honour at the Press Club and aviation institutions. In a visit to Old Warden she was re-united with the Gull, where it had been since 1961. Sadly it was unserviceable at the time and Jean couldn't enjoy a flight. A special tour of the prototype Concorde at Fairford ignited a new goal. Jean wanted to fly in it to New Zealand ’in half a day’.

In all her interviews – and in most of her conversation - she talked at length about herself and her flights, clearly recalling details. But at a time when man was walking on the moon she was a creature of the past and seldom recognised. Her free week at the Waldorf extended into a month before they could ‘prise her out’.

In all her interviews – and in most of her conversation - she talked at length about herself and her flights, clearly recalling details. But at a time when man was walking on the moon she was a creature of the past and seldom recognised. Her free week at the Waldorf extended into a month before they could ‘prise her out’.

She left, on impulse, to fly to New Zealand, this time in a Boeing 747. Most of the flight was spent in the cockpit, fascinated by the torrent of radio traffic. It was one of several visits triggered by invitations over the next 10 years to Australia, the USA and England. The hair changed to brunette, then to blond and there was another face-lift. Usually, she stayed with, or at the expense, of her hosts. The last of these was Bob Pooley, the publisher. When she left in 1982 she said ‘I’m going to ground. You won’t see me again.’ She left a note giving her address as poste restante, Palma, Majorca. A letter written to Pooley’s publishing company dated 8 November 1982 is the last that was heard of Jean.

As time went on and expected contacts from Jean failed to arrive the Pooleys made enquiries, first in Spain then via the New Zealand High Commission. When this produced no result the search widened and more authorities were involved. Barclays Bank, where Jean had an account, refused to release any information. Informal enquiries in the correspondence columns of Flight International and official searches via the Spanish Embassy were no help. All searches petered out after five years.

In the end, it was the persistent and diligent research of Ian Mackersey and his wife, Caroline, which uncovered the true facts. (Ian Mackersey is a New Zealander himself, an aviation author and documentary maker who has written a biography of ‘Jean Batten - The Garbo of the Skies’ from which many of the facts in this article are drawn).

When Jean arrived in Palma in 1982 she had bought a small apartment. She was seen only on long solitary walks. On one of these, she was bitten on the leg by a dog. It was not a rabid dog but the wound became infected. She refused all medical help. The infection spread to a lung and on 22 November 1982 she died of a pulmonary abscess, in normal circumstances, easily treated. She had been in Majorca only a few weeks, no one knew who she was and little effort was made to find out. She was buried in a communal, or paupers’, grave. A notification was sent to the New Zealand embassy in Madrid. That got nowhere because an embassy did not exist, diplomatic relations at the time being handled by the NZ embassy in Paris. The circumstances of her death had remained a mystery for five years.

In 1987, The Hunting Group and Shuttleworth made the Gull serviceable again and it was displayed in Auckland airport in 1990, the 25th anniversary of the airport’s opening.

You can enjoy Ian Mackersey’s film here: http://www.nzonscreen.com/title/jean-batten---the-garbo-of-the-skies-1988

As time went on and expected contacts from Jean failed to arrive the Pooleys made enquiries, first in Spain then via the New Zealand High Commission. When this produced no result the search widened and more authorities were involved. Barclays Bank, where Jean had an account, refused to release any information. Informal enquiries in the correspondence columns of Flight International and official searches via the Spanish Embassy were no help. All searches petered out after five years.

In the end, it was the persistent and diligent research of Ian Mackersey and his wife, Caroline, which uncovered the true facts. (Ian Mackersey is a New Zealander himself, an aviation author and documentary maker who has written a biography of ‘Jean Batten - The Garbo of the Skies’ from which many of the facts in this article are drawn).

When Jean arrived in Palma in 1982 she had bought a small apartment. She was seen only on long solitary walks. On one of these, she was bitten on the leg by a dog. It was not a rabid dog but the wound became infected. She refused all medical help. The infection spread to a lung and on 22 November 1982 she died of a pulmonary abscess, in normal circumstances, easily treated. She had been in Majorca only a few weeks, no one knew who she was and little effort was made to find out. She was buried in a communal, or paupers’, grave. A notification was sent to the New Zealand embassy in Madrid. That got nowhere because an embassy did not exist, diplomatic relations at the time being handled by the NZ embassy in Paris. The circumstances of her death had remained a mystery for five years.

In 1987, The Hunting Group and Shuttleworth made the Gull serviceable again and it was displayed in Auckland airport in 1990, the 25th anniversary of the airport’s opening.

You can enjoy Ian Mackersey’s film here: http://www.nzonscreen.com/title/jean-batten---the-garbo-of-the-skies-1988