Boeing Strato-tanker (Dec 2019)

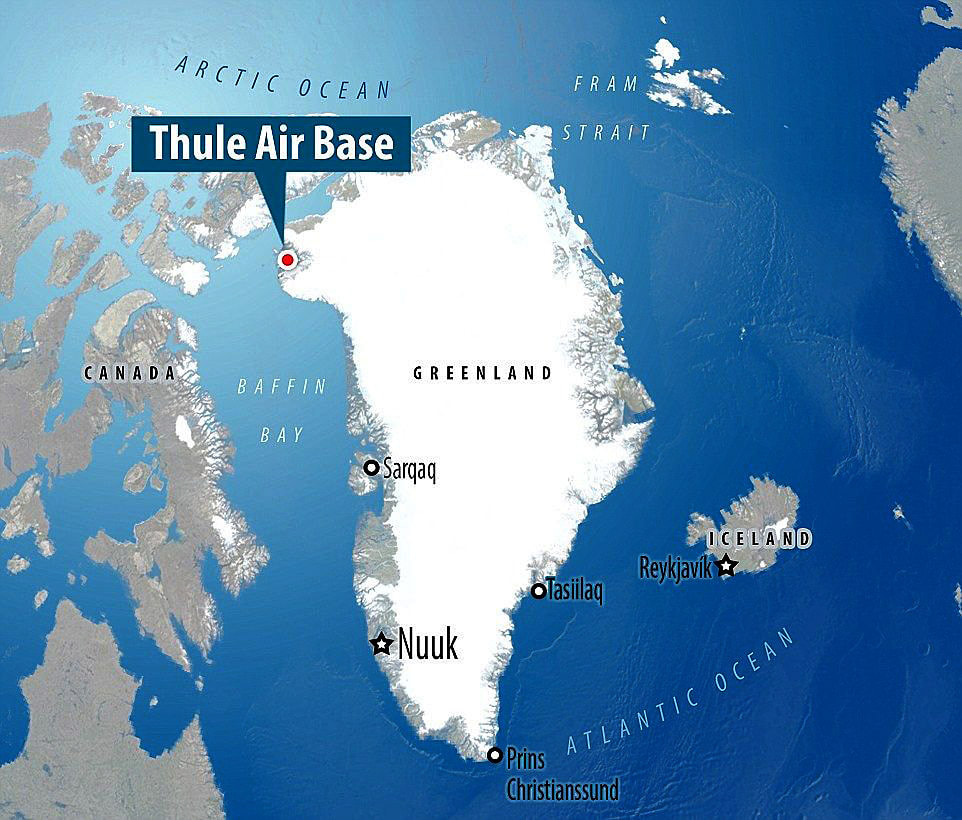

Max Barton was quite pleased with his lot. On his exchange posting to the USAF he was trained and qualified as a tanker captain, flying the Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighter. Not only that, he had been posted to the USAF’s most extreme outposts, Thule, northern Greenland. Far from home, the airmen based there were at the very front line of the Cold War – cold in more sense than one.

The US had been in Greenland since 1941 when it built radio and weather stations at Thule to keep an eye on German operations in northern Norway and the arctic seas. In the early 50s one of the first radar stations of the DEW (Distant Early Warning) line was set up there, the new frontier in the Cold War.

Thule is piece of flat land on the coast bordering a deep water bay and convenient for the building of a ‘giant air base on top of the world’. 12,000 men and 300,000 tons of cargo arrived in July 1951 and round the clock construction began in the continuous daylight of the arctic summer. It was all meant to be done in secret but a French geographer on his way back from the north magnetic pole stumbled across it. (What was kept secret was the other station, nuclear powered, 150 miles from Thule on the Greenland ice-cap. Its network of tunnels housed launching pads for ICBM missiles. It was eventually abandoned as impractical. The nuclear unit was taken home and the rest allowed to sink into the ice-cap).

Although the air base at Thule was to be built on ‘land’ it certainly wasn’t rock – it was frozen tundra – just as hard rock as long as it stayed frozen. But a heated building sitting on the tundra could unfreeze it and the building would slowly subside. Aeroplanes can’t easily be pulled in and out of a sunken hangar. So the first job for the construction engineers was to install refrigeration units in the foundations to keep the tundra frozen. Then, after suitable insulation, the heating units came next and finally the buildings.

Thule is piece of flat land on the coast bordering a deep water bay and convenient for the building of a ‘giant air base on top of the world’. 12,000 men and 300,000 tons of cargo arrived in July 1951 and round the clock construction began in the continuous daylight of the arctic summer. It was all meant to be done in secret but a French geographer on his way back from the north magnetic pole stumbled across it. (What was kept secret was the other station, nuclear powered, 150 miles from Thule on the Greenland ice-cap. Its network of tunnels housed launching pads for ICBM missiles. It was eventually abandoned as impractical. The nuclear unit was taken home and the rest allowed to sink into the ice-cap).

Although the air base at Thule was to be built on ‘land’ it certainly wasn’t rock – it was frozen tundra – just as hard rock as long as it stayed frozen. But a heated building sitting on the tundra could unfreeze it and the building would slowly subside. Aeroplanes can’t easily be pulled in and out of a sunken hangar. So the first job for the construction engineers was to install refrigeration units in the foundations to keep the tundra frozen. Then, after suitable insulation, the heating units came next and finally the buildings.

The first aircraft based at Thule were B-47 Stratojet bombers at least one of which was to be continuously airborne. Two hours after take-off the B-47 needed refueling and would take the contents of two KC-97 Stratofreighter tankers. A third taker always accompanied the others just in case. And if there was a problem which prevented a tanker taking off in this unfriendly and hazardous environment a fourth tanker was prepared for take-off. Experience showed that that was a wise precaution and was needed so often that it became normal practice to prepare no fewer than five tankers. They would sit outside, ready for flight with their twenty 28-cylinder Wasp Major engines running in temperatures as low as -46°C.

Three would take off and climb to the rendezvous point. They would meet the B-47 which, after take-off and two hours cruise would have near empty tanks. Two tankers would, in turn, fly a race-track pattern and fuel the B-47 which could now fly for another seven hours. They two empty tankers and the third which had been on stand-by would return to base.

Before the B-47 landed a second bomber would get airborne and the whole procedure would start again. Managing fuel was critical at Thule. If the weather closed in and landing there was impossible the ‘nearby’ alternate airfields available were in Labrador, Alaska or England.

Before the B-47 landed a second bomber would get airborne and the whole procedure would start again. Managing fuel was critical at Thule. If the weather closed in and landing there was impossible the ‘nearby’ alternate airfields available were in Labrador, Alaska or England.

Soon the B-47s were replaced by 10-engined B- 36s using two kinds of fuel. Another RAF exchange-posted pilot experienced patrols on these – Sqn Ldr Ken Wallis - and told tales of 33-hour flights with two crews aboard. That kept the tankers busy.

The B-36s were replaced in turn by B-52s. The KC-97s soldiered on. Their cruising speed of 230 mph was not comfortable for the B-52. The bomber pilots would lower their flaps and undercarriage to keep in close formation with the tanker. An alternative ploy was to refuel in a gradual descent which speeded up the tanker.

Flt. Lt. Max Barton was one of the pilots of the 25th Air Refuelling Squadron at Thule. He had joined the RAF in 1944 as an 18 year old and flew as a Lancaster navigator. At the end of the war he was demobbed and trained in aeronautical engineering, going to work in the research and development department of Avro on the design of the Vulcan. However, he wanted to fly again and rejoined the RAF for pilot training. He was a keen student and graduated at the top of the course, winning all three trophies. He was ideally suited to respond to the challenges of this demanding arctic posting.

It was 27th November 1956 and the sun had set a couple of months ago. Barton was flying a KC-97 Stratofreighter, call sign ‘Turmoil 5’, and waiting at 15,000 ft to refuel a B-52. Alongside him was 2nd Lt Nick Nicholls, his co-pilot and behind, in the warm pressurised cabin, were the navigator, radio operator and flight engineer. The boom operator had moved to his position back in the tail. (The USAF used the boom because it could deliver fuel at 6000 lbs per minute for the thirstier bombers. The probe and drogue, with its 1000 – 3000 lbs per min delivery was suitable for fighters and smaller jets).

Capt Jim Sullivan, the navigator, monitored on his radar the slow approach of the B-52 as it crept towards the tanker.

Staff Sgt Painter, lying on his couch in the cold, unpressurised tail, took over the radio link with the B-52 pilot and manoeuvred the boom until it locked into position behind the bomber’s cockpit. The JP-4 flowed.

A boom operator at work. (The receiver is not a B-52).

Capt Jim Sullivan, the navigator, monitored on his radar the slow approach of the B-52 as it crept towards the tanker.

Staff Sgt Painter, lying on his couch in the cold, unpressurised tail, took over the radio link with the B-52 pilot and manoeuvred the boom until it locked into position behind the bomber’s cockpit. The JP-4 flowed.

A boom operator at work. (The receiver is not a B-52).

Standing alongside Painter was Staff Sgt Morris Carman, the radio operator. He used a torch to check on the array of pipes, valves and junctions through which the fuel flowed under pressure.

The refuelling was almost half finished when Carman heard a noise, above the sound of the engines. The loud hissing was accompanied by the overwhelming small of escaping fuel.

Both man clamped their masks tightly to their faces and turned the oxygen flow to full. Painter shut off the fuel, retracted the boom and waved it from side to side, signalling to the B-52 pilot that refueling was ended.

Barton reacted quickly. The fuel was leaking uncontrollably into the fuselage and a tiny spark could cause a fire. He told the engineer to switch off the main electricity supply. The radio, intercom and most of the instruments and navigation equipment died. The heating also failed and the aircraft was de-pressurised. The emergency power supply kept only reduced cockpit lighting and three instruments working – the artificial horizon, turn and slip indicator and directional gyro. Jim Sullivan had to use dead reckoning to work out the course for Thule, some 250 miles away. Barton carefully turned to the new heading and descended to 10,000 ft.

In the turmoil of the rear fuselage, Painter traced the leak to a 3 inch long break in one of the pipes. Fuel was gushing out at, at least, 50 gallons a minute. There was no way it could be staunched. The two men came forward and told Barton of the situation, having to take off their masks and shout in the pilot’s ear.

Barton told the crew to jettison hatches to try to clear the worst of the fumes and an icy gale swirled through the aircraft. The lower hatch at the rear, which would have allowed some of the fuel to drain away, refused to move. Fuel leaking through gaps had frozen and they didn’t dare risk a spark by trying to hammer it open. The loose fuel was filling the fuselage, sloshing around and affecting the trim. Barton realized that anything other than the gentlest of pitching movement could cause runaway instability. Another potential problem was developing. Without power the de-icing equipment wasn’t working and they could see a slow, thankfully very slow, build up on the wings.

The KG-97 crept towards Thule and after a very long hour, the glow of its lights appeared. Barton considered his options. He was confident that he could get the tanker lined up with the runway for landing but he wouldn’t be able to work out the correct speed for approach. The lack of electrical power had disabled the flaps and the trim system and he didn’t know if there even was a recommended speed for a flapless approach. He could only guess the tanker’s weight, which also affects the approach speed. When he flared for the landing and the nose pitched up the fuel would rush to the back. This could either cause a stall or make the tail bumper strike the runway and put a spark under his flying bomb.

Whether he tried to land or not he reasoned that it would be safest for the crew to bail out when they reached the airfield. Each crew member was given a shouted briefing and all but the co-pilot, Nick Nicholls, elected to jump. First, they had to wind down the undercarriage. In the icy darkness they struggled with the levers and cranks which had to be used in the correct sequence. Finally, they pronounced that it was down. The green lights on the panel which normally confirmed this stayed unlit.

Barton lined up the tanker with the runway. At 5000 ft he flew as slowly as he could, 160 mph. Then one by one, the crew forced themselves out into the slipstream and four parachutes floated down safely onto the airfield. Gently, the tanker was swung in a wide circle to approach the runway for the landing. Suddenly, the panel lighting went out. The stand-by battery was exhausted. Barton was particularly grateful that Nicholls was still with him. His pocket torch illuminated the last working instruments, the altimeter and the essential airspeed indicator.

Starting from a long way out the ‘high’ speed approach was much shallower than normal. Barton held the airspeed at 160 mph and thought he could reduce to 145 for touchdown. On the airfield, the rescue services had been alerted by the parachutists and were wailing into position. In the flickering reflections of the runway lights on the icy ground, Barton realized he was still too high and shouted to Nicholls to reduce power a little. The KC-97 sank a couple of hundred feet and Nicholls yelled out the airspeed ‘150 …145 … 140 …135 …135’.

The tanker was skimming the surface with the fuselage almost horizontal. Unlike the civilian Stratocruisers which landed nose wheel first it was the tanker’s mainwheels which thumped onto the runway. The loose fuel had moved the Centre of Gravity towards the tail and the nose wheel remained obstinately in the air. Barton held the control wheel fully forward but the nose stayed high. Until it was on the runway, he couldn’t safely use the brakes and the tanker was rapidly using up the runway at over 100 mph. At this rate of mis-use – overweight and over speed – the main undercarriage could collapse with much scraping and sparking.

The manual said brakes shouldn’t be used at all over 60 mph. Barton applied a momentary touch. It was enough. The main wheels slowed for a fraction of a second and the nose wheel dropped. Barton rejected the manual’s advice and pushed the brake pedals to the floor. Gradually the tanker lost momentum and eventually came to a stop, having used 7,500 ft of runway.

In the silence after the engines were shut down the ticking of the cooling machinery was echoed by the dripping of the fuel from every part of the fuselage including the forward escape hatch. The pilots decided not to risk trying to use that and called for a rope so that they could slide to the ground from the cockpit windows. Wisps of smoke were still curling from the mainwheels’ brakes.

For the way in which he had saved a valuable aeroplane - and the lives of the crew - Max Barton was awarded the American Distinguished Flying Cross for ‘outstanding bravery in the air’.

__________________________________________________

In the turmoil of the rear fuselage, Painter traced the leak to a 3 inch long break in one of the pipes. Fuel was gushing out at, at least, 50 gallons a minute. There was no way it could be staunched. The two men came forward and told Barton of the situation, having to take off their masks and shout in the pilot’s ear.

Barton told the crew to jettison hatches to try to clear the worst of the fumes and an icy gale swirled through the aircraft. The lower hatch at the rear, which would have allowed some of the fuel to drain away, refused to move. Fuel leaking through gaps had frozen and they didn’t dare risk a spark by trying to hammer it open. The loose fuel was filling the fuselage, sloshing around and affecting the trim. Barton realized that anything other than the gentlest of pitching movement could cause runaway instability. Another potential problem was developing. Without power the de-icing equipment wasn’t working and they could see a slow, thankfully very slow, build up on the wings.

The KG-97 crept towards Thule and after a very long hour, the glow of its lights appeared. Barton considered his options. He was confident that he could get the tanker lined up with the runway for landing but he wouldn’t be able to work out the correct speed for approach. The lack of electrical power had disabled the flaps and the trim system and he didn’t know if there even was a recommended speed for a flapless approach. He could only guess the tanker’s weight, which also affects the approach speed. When he flared for the landing and the nose pitched up the fuel would rush to the back. This could either cause a stall or make the tail bumper strike the runway and put a spark under his flying bomb.

Whether he tried to land or not he reasoned that it would be safest for the crew to bail out when they reached the airfield. Each crew member was given a shouted briefing and all but the co-pilot, Nick Nicholls, elected to jump. First, they had to wind down the undercarriage. In the icy darkness they struggled with the levers and cranks which had to be used in the correct sequence. Finally, they pronounced that it was down. The green lights on the panel which normally confirmed this stayed unlit.

Barton lined up the tanker with the runway. At 5000 ft he flew as slowly as he could, 160 mph. Then one by one, the crew forced themselves out into the slipstream and four parachutes floated down safely onto the airfield. Gently, the tanker was swung in a wide circle to approach the runway for the landing. Suddenly, the panel lighting went out. The stand-by battery was exhausted. Barton was particularly grateful that Nicholls was still with him. His pocket torch illuminated the last working instruments, the altimeter and the essential airspeed indicator.

Starting from a long way out the ‘high’ speed approach was much shallower than normal. Barton held the airspeed at 160 mph and thought he could reduce to 145 for touchdown. On the airfield, the rescue services had been alerted by the parachutists and were wailing into position. In the flickering reflections of the runway lights on the icy ground, Barton realized he was still too high and shouted to Nicholls to reduce power a little. The KC-97 sank a couple of hundred feet and Nicholls yelled out the airspeed ‘150 …145 … 140 …135 …135’.

The tanker was skimming the surface with the fuselage almost horizontal. Unlike the civilian Stratocruisers which landed nose wheel first it was the tanker’s mainwheels which thumped onto the runway. The loose fuel had moved the Centre of Gravity towards the tail and the nose wheel remained obstinately in the air. Barton held the control wheel fully forward but the nose stayed high. Until it was on the runway, he couldn’t safely use the brakes and the tanker was rapidly using up the runway at over 100 mph. At this rate of mis-use – overweight and over speed – the main undercarriage could collapse with much scraping and sparking.

The manual said brakes shouldn’t be used at all over 60 mph. Barton applied a momentary touch. It was enough. The main wheels slowed for a fraction of a second and the nose wheel dropped. Barton rejected the manual’s advice and pushed the brake pedals to the floor. Gradually the tanker lost momentum and eventually came to a stop, having used 7,500 ft of runway.

In the silence after the engines were shut down the ticking of the cooling machinery was echoed by the dripping of the fuel from every part of the fuselage including the forward escape hatch. The pilots decided not to risk trying to use that and called for a rope so that they could slide to the ground from the cockpit windows. Wisps of smoke were still curling from the mainwheels’ brakes.

For the way in which he had saved a valuable aeroplane - and the lives of the crew - Max Barton was awarded the American Distinguished Flying Cross for ‘outstanding bravery in the air’.

__________________________________________________

Although many of its customers became too fast for it the KC-97 was otherwise a very efficient tanker. To keep them in service, some were fitted with jet pods to make them more capable of servicing jet aircraft. Their designation was KC-97L. It was not finally withdrawn from service until 1978.

Its replacement was the KC-135. The prototype first flew in 1956. Although it looked like a conversion of the Boeing 707 it was not. Both had the same parent, the Boeing 367-80, a one-off design built solely to prove the viability of the swept-wing, four dangling engine pods layout.

The KC-135 Stratotanker has a smaller, slimmer fuselage than the 707. Its load of fuel occupies less space than 200 passengers and their baggage. The ubiquitous KC-135 came into service in 1957. It has celebrated its 60th anniversary and is predicted to be still around in 2030.

|

Just a few years after Max Barton’s episode the US Navy’s submarines took over nuclear deterrent duties and the round the clock airborne deterrents were no longer needed. Thule’s primary role changed and increasingly sophisticated radar and surveillance systems arrived to keep a close watch on the USA’s over-the-pole neighbour. Today, over 600 personnel of the Air Force Space Command man the base with a Test Wing (Satellite), Missile Warning Group and, of course, an Air Base Group to handle the traffic.

|

Many units from Nato as well as US forces go to Thule on short-term attachments, to take part in exercises or just to practise operating in the punishing Arctic conditions.

Some of the older buildings have been abandoned but all essential facilities are kept in full operational order. Thule has been used, occasionally, by civilian airlines and has even been host to the odd tourist. |