In the Wake of the Caspian Sea Monster (July 2017)

It was a satellite image which seems to have brought it to the world’s notice. Parked on the ramp of a Russian naval port was what looked like a large seaplane with very short wings. US intelligence found the letters KM. K for Kaspian, M for . . . Monster? (‘Korabl maket’ in Russian actually meant ‘prototype ship’). This was back in 1966 and the more that was learned about it, the more astonishing it was.

Rostislav Evgenievich Alexeyev trained as a ship designer and wrote his thesis on ‘A Planing Boat with Hydrofoils’. It was highly regarded, but this was 1941 and he was needed in a factory producing T-34 tanks. After Stalingrad, he was allowed to work on his ‘high speed boat’ for one hour a day. It wasn’t until the war ended that he was able to produce a series of successful hydrofoils. By the late 50s, more than 300 of his boats were in service.

Alexeyev knew – as do all pilots – that when flying close to the ground (or the water) a wing produces more lift and the plane seems to float on a cushion of air. (As far back as 1929, the ground effect had been used by the 12-engined, under-powered Dornier X. For the first three hours of its trans-Atlantic flight it flew just above the waves until enough of its 21,000 gallons fuel load had been burnt off to allow it to climb).

Rostislav Evgenievich Alexeyev trained as a ship designer and wrote his thesis on ‘A Planing Boat with Hydrofoils’. It was highly regarded, but this was 1941 and he was needed in a factory producing T-34 tanks. After Stalingrad, he was allowed to work on his ‘high speed boat’ for one hour a day. It wasn’t until the war ended that he was able to produce a series of successful hydrofoils. By the late 50s, more than 300 of his boats were in service.

Alexeyev knew – as do all pilots – that when flying close to the ground (or the water) a wing produces more lift and the plane seems to float on a cushion of air. (As far back as 1929, the ground effect had been used by the 12-engined, under-powered Dornier X. For the first three hours of its trans-Atlantic flight it flew just above the waves until enough of its 21,000 gallons fuel load had been burnt off to allow it to climb).

Alexeyev wanted a really high speed boat, so why not add short wings to lift it clear of the surface and eliminate water drag entirely. His first ekranoplan design, the SM-1 was powered by a single turbojet. It had poor handling and a very high take-off speed although it worked well enough to encourage the Defence Minister to allocate more funds after he was impressed by a ride in it. Testing was brought to an end in 1960 by a hangar fire.

Alexeyev wanted a really high speed boat, so why not add short wings to lift it clear of the surface and eliminate water drag entirely. His first ekranoplan design, the SM-1 was powered by a single turbojet. It had poor handling and a very high take-off speed although it worked well enough to encourage the Defence Minister to allocate more funds after he was impressed by a ride in it. Testing was brought to an end in 1960 by a hangar fire.

The SM-2 had a second turbojet mounted in the nose with the exhaust directed below the wings. It performed a little better but the prolonged take-off still made the craft impractical. The SM-3, -4 and 5 developed more effective nozzles to spread the lift over a wider area and the tailplane and fin were greatly increased in size.

In his experiments, Alexeyev found that the bigger the craft was, the more efficient it was. The SM-8 was built as the ¼ scale version of the full-size KM. It worked well, although everyone lost interest in it when the full size version appeared.

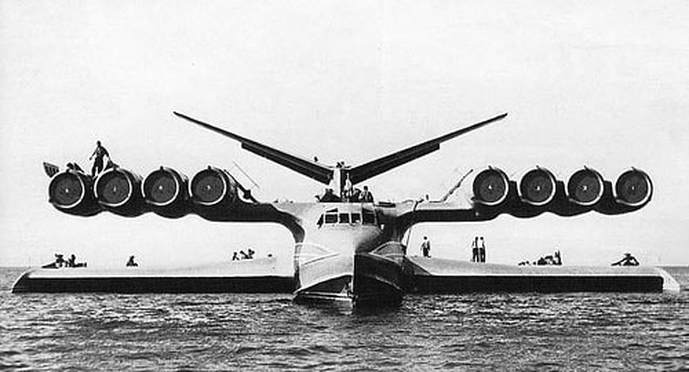

It was the mighty KM which the satellite had found, a 300 feet long monster of over 500 tons.

Note the deflected nozzles of the port bank of jets in the take off position

The first ‘flight’ was in October 1966 with, unusually, the designer at the controls. It was powered by ten Dobryin VD-7 turbojets, each producing 28,000 lbs thrust. Most of this power was needed just to get it off the water. In cruise, that's 232 knots, only the tail mounted engines were needed. A series of modifications were tested, identified by the number on the fin. At one stage, the twin tail engines were re-located to the top of a pylon above the other eight engines.

The KM soldiered on until 1980. The end came when they tried to solve the lift-off problem by taking off at reduced power. The wreck sank in shallow water and was abandoned. It was too heavy to salvage.

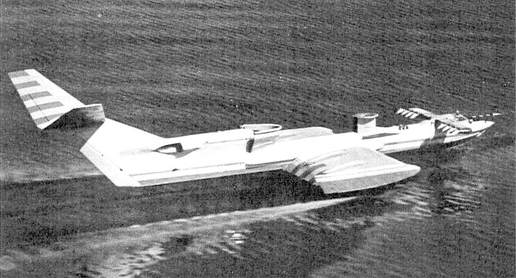

Meanwhile, other ekranoplans had been tested. The A 90 Orlyonok (‘Little Eagle’) was first tested on the Volga river in 1973. It was intended as a troop transport and assault vehicle. Smaller than the KM – 190 ft long, 110 tons – it was powered by a 14,000 hp Kuznetsov turboprop for cruise and two nose mounted turbofans for take off. The wing had a five-section flap/aileron and there were two hydroskis under the fuselage. There were plans to build 120 but only 4 were produced, serving with the Soviet Navy until 1983.

Meanwhile, other ekranoplans had been tested. The A 90 Orlyonok (‘Little Eagle’) was first tested on the Volga river in 1973. It was intended as a troop transport and assault vehicle. Smaller than the KM – 190 ft long, 110 tons – it was powered by a 14,000 hp Kuznetsov turboprop for cruise and two nose mounted turbofans for take off. The wing had a five-section flap/aileron and there were two hydroskis under the fuselage. There were plans to build 120 but only 4 were produced, serving with the Soviet Navy until 1983.

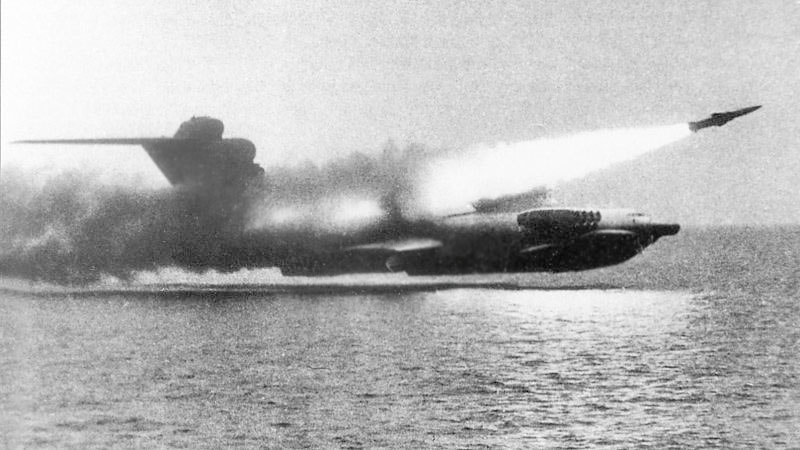

Next there was the Lun (‘Hen Harrier’). Looking like a smaller KM it weighed 280 tonnes empty and cruised at 342 mph. Its 100 tonnes payload included six anti-ship missiles and two gun turrets each with a pair of 23mm cannon. A more peaceful twin was being fitted out as a hospital and rescue vehicle when the collapse of the Soviet Union brought all plans to a halt.

Alexeyev was not the only builder of serious skimmers. Robert Ludvigovich Bartini was an Italian communist who didn’t get on with Mussolini’s Fascist regime. He escaped to Russia in 1923 and rose in the hierarchy of designers of ‘experimental amphibious aircraft’. For some reason he was imprisoned from 1938 to 1946. Then for the next six years he was allowed to continue his design work with the Beriev Aircraft Company. His interests were widespread – a jet-powered flying boat strategic bomber, even a nuclear powered hydroplane. In 1961 he designed a WIG (wing in ground effect) vehicle. Curiously, it was intended to be comprehensively capable - amphibious, fitted with lift engines for VTOL, and fitted with an extended wing to allow it to fly.

The Bartini-Beriev VVA-14 emerged in 1972 fitted with a wheeled undercarriage. Inflatable floats were added, later changed to rigid floats and water tests started in 1975. Sadly, Bartini was not to see these – he had died the previous year. The VTOL engines were never delivered. Although it was capable of ‘sea skimming’ its big wing allowed it to fly as high as 3000 metres. After 107 flights it was retired to a museum in 1987 where it sits to this day like a tired tortoise.

Russia did not have the monopoly in building WIGs, though no-one else took them to such enormous sizes. A successful designer was Alexander Lippisch. Born in Germany in 1894 he first came to the fore in the 1920s as the designer of the SG-38 training glider and several advanced sailplanes. He was keenly interested in delta-winged tailless aircraft and made many experimental test models which led, eventually, to the Messerschmitt 163. Operation Paperclip in 1945 scooped him up with other scientists and he moved to the States.

Russia did not have the monopoly in building WIGs, though no-one else took them to such enormous sizes. A successful designer was Alexander Lippisch. Born in Germany in 1894 he first came to the fore in the 1920s as the designer of the SG-38 training glider and several advanced sailplanes. He was keenly interested in delta-winged tailless aircraft and made many experimental test models which led, eventually, to the Messerschmitt 163. Operation Paperclip in 1945 scooped him up with other scientists and he moved to the States.

Whilst working for the aeronautical division of Collins Radio he was asked to develop a ‘fast motor boat’. He decided to harness the ground (or water) effect. Using his delta wing, he reversed it so that it had a straight leading edge and added anhedral to help trap the air cushion. First flown in 1963, the X-112 was a success and could fly at a height equivalent to 50% of its span (Alexeyev’s monsters were limited to 10% of their span).

Tests came to a halt when Lippisch contracted cancer and he resigned from Collins. When he recovered, he formed his own company and moved back to Germany to work with Rhein-Flugzeugbau (RFB). The X-113 was exhibited at the 1973 Paris Air Show. It was small – 19’4” span, 27’8” long with a 40 hp engine – and cruised at 50 mph. It was tested over Lake Constance and over a ‘rough’ North Sea, reaching 1500 ft out of ground effect.

This performance was sufficient to trigger the interest of the German navy who thought it would be useful in the Baltic and the X-114 was built. With a 200 hp Lycoming it could carry six passengers and cruise at 93 mph. An indication of the efficiency of flying in ground effect is the X-114’s range of 1,250 miles – 20 hours endurance.

Although the tests were eminently successful, there was no production order.

Lippisch had died before the X-114 appeared but his work was carried on by Hanno Fischer who developed a series of test vehicles all named Airfish. Airfish 8 attracted the attention of a Singaporean-Australian venture calling itself Flightship. Airfish 8 was taken to Singapore and extensive sea trials took place there, in Thailand, and in Australia.

With commercial use looming, regulatory authorities began to take notice, in Singapore, Australia, Germany and the USA. WIG vehicles operate sometimes like ships when they are afloat and sometimes like aeroplanes – seriously anti-social low flying aeroplanes whizzing noisily through often congested areas of rivers, estuaries and sea lanes.

Take offs must be directly into wind. If one wing lifts before the other the asymetric drag can spin the craft round and cause the sort of crash which wrote off Alexeyev’s KM. Take off also has all the problems experienced by flying boats, requiring full power to overcome water drag and get to unstick speed. And unstick is reached only when the wing splashing through the spray generates sufficient lift. The Russians used deflected jet blast to help but afterwards the nose engines, not needed in cruise, became useless dead weight. Lippisch’s anhedralled wing was rather better at getting ‘on the step’.

Once airborne, power can by reduced by more than 50% and the pilot can settle into a fast, comfortable and very efficient cruise. But the lower he flies, the less the pilot can see ahead and he needs to avoid any obstacles. If the craft can fly out of ground effect, it can hop over a sandback, or even a line of moored yachts. Otherwise it must be turned and the limited amount of bank available means that all turns are gentle and can’t be left to the last minute.

So how can all these conflicting methods of operation fit into the rules. In the end, WIGs were treated broadly as fast motor boats. Airfish 8 was formally registered as a ship by the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore in March 2010. In Australia, Flightship craft appeared in Lloyds Register. (It was all rather academic. The ownership of Airfish/Flightship shuttled between various organizations who took turns in going broke).

The International Maritime Organization groups ground effect craft carrying 12 passengers or more into three classes. Type A: certified for operation only in ground effect; Type B: certified to temporarily fly outside the ground effect to a maximum of 150 m above the surface; and Type C: certified for operation outside ground effect and exceeding 150 m above the surface. (How the Maritime Organisation can regulate what is now an aircraft isn’t clear). All three types are required to be fitted with a collision avoidance system.

Take offs must be directly into wind. If one wing lifts before the other the asymetric drag can spin the craft round and cause the sort of crash which wrote off Alexeyev’s KM. Take off also has all the problems experienced by flying boats, requiring full power to overcome water drag and get to unstick speed. And unstick is reached only when the wing splashing through the spray generates sufficient lift. The Russians used deflected jet blast to help but afterwards the nose engines, not needed in cruise, became useless dead weight. Lippisch’s anhedralled wing was rather better at getting ‘on the step’.

Once airborne, power can by reduced by more than 50% and the pilot can settle into a fast, comfortable and very efficient cruise. But the lower he flies, the less the pilot can see ahead and he needs to avoid any obstacles. If the craft can fly out of ground effect, it can hop over a sandback, or even a line of moored yachts. Otherwise it must be turned and the limited amount of bank available means that all turns are gentle and can’t be left to the last minute.

So how can all these conflicting methods of operation fit into the rules. In the end, WIGs were treated broadly as fast motor boats. Airfish 8 was formally registered as a ship by the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore in March 2010. In Australia, Flightship craft appeared in Lloyds Register. (It was all rather academic. The ownership of Airfish/Flightship shuttled between various organizations who took turns in going broke).

The International Maritime Organization groups ground effect craft carrying 12 passengers or more into three classes. Type A: certified for operation only in ground effect; Type B: certified to temporarily fly outside the ground effect to a maximum of 150 m above the surface; and Type C: certified for operation outside ground effect and exceeding 150 m above the surface. (How the Maritime Organisation can regulate what is now an aircraft isn’t clear). All three types are required to be fitted with a collision avoidance system.

After perestroika and glasnost the monster WIGs were too expensive to revive and several design bureax turned to smaller vehicles, mostly using the Russian, straight-winged layout. Some experimented with Lippisch’s reverse delta and a third, tandem-wing layout that had been developed by Günther Jorg in Germany.

These are Amphistar 4-seat WIG. Developed in Russia, they were painfully taken through the full certification process for operation in Russia and the USA, but not in Europe – the German authorities proved to be too inflexible. In the States, Amphistar even went as far as arranging special insurance. Preparations were made for a production plant to be built in Virginia.

Demonstrations raised considerable enthusiasm and an encouraging amount of promised finance but - no order.

Making money out of a commercial operation using WIGs seems to be a step too far but you might want to own one, just for the joy of high-speed over-the-water travel. ATTK-Invest will let you choose an Aquaglide 5 from their forecourt. You might get a good rouble discount – they’ve just announced their latest model 6.

Not all eyes were on commerce. One group showed the Russian sense of humour by experimenting with Lippisch’s reverse delta. They started with an Antonov An-2 biplane and finished with -- this. Maybe they’re going to do something about the undercarriage and prop clearance.

All the work going on in Russia has been noted by the Chinese. They were particularly taken with the Ivolga EK-12, used in the Archangel area and by the Border Guard forces. It carries 12 people and is powered by two Chevrolet engines. It is now being built under licence in China as the Hainan Yingge CYG-11.

They say they’ve already built a larger craft to carry 40 people and have plans for an even bigger model, (55-120 passengers) but the Chinese have also expressed serious interest in Russia’s latest 050 ekranoplan. Weighing 54 tons and capable of carrying 100 people at speeds up to 260 mph it is here fitted with skis and clearly intended for operations from the new Polar station being built on an island north of Siberia. Significantly, another version could be armed with cruise missiles.

Meanwhile, what’s been going on in the land of the free? The US Army carried out an Advanced Mobility Concepts Study in 2003. Everything was considered, including airships. It was Boeing who offered the Pelican, an Ultra Large Transport Aircraft – a WIG. They proposed three versions, the largest with a 500 ft span, weighing 2,450 tons. It would operate from runways, running on 38 pairs of wheels, each pair being steerable to could cope with crosswinds. Boeing thought that as many as 1,000 Pelicans would be needed by 2020. The Army thought otherwise.

Although there are few commercial WIG operators lots of people are having lots of fun, largely by building their own or converting a boat or hovercraft.

Taras Kiceniuk, from California, was a keen hang-glider builder. He decided to attack the Kremer prize for human-powered aircraft with a WIG. It worked, apart from the turns needed to complete the figure 8 course. He abandoned it to join Paul MacReady (who won the prize).

You might be getting the impression that however ingenious and efficient WIG craft are they are quite impractical for serious use. That view is clearly not shared by that great sea power, the Navy of Iran. They have three squadrons of Bavar 2 patrol craft. The two crewmen are armed with machine guns and missiles, allowing them to be even more aggressive against any intruders in their waters in the Gulf.

The wing in ground effect doesn’t seem to intrude in the thinking of designers of ‘normal’ aeroplanes. It is just one of many atmospheric conditions that pilots have to cope with – turbulence, downdraughts, mountain waves etc. And there are different ways of coping.

The Miles Gemini arose out of the ditching of a single-engined Messenger. Two engines could add over-water safety and a pair of Cirrus Minor engines did the trick. It turned out to be a very pleasant, successful aeroplane. First flown in October, 1945, 170 were produced. Each engine sat between two fuel tanks and there was enough fuel, 66 gallons, for a surprising range of nearly 1000 miles.

A charter pilot was scheduled to fly four passengers and their luggage from Liverpool to Dublin. Conscious of over-loading, he told the ground crew to make sure there was no more than 5 gallons in each of the outer tanks. He checked and the gauges did, indeed, show 5 gallons

The take-off was distinctly sluggish. There was a large factory on one side of the runway and the pilot looked up at it as the Gemini staggered past and over the boundary road. He was aware of a recent accident to an over-loaded Gemini when the pilot tried to pull up the nose into a climb and the Gemini sank to the ground and crashed. He kept low, making full use of the ground effect and crept over the Mersey. He managed to avoid the shipping as they flew down the river. It wasn’t until they were well over the Irish Sea that the speed had increased enough to climb to 1000 ft. Fortunately, the passengers were quite unaware of the danger they’d been in and, on landing, thanked the pilot for giving them such a close view of the docks.

Back at base, he learned that the fuelling had been done by a mechanic who had started just the day before. The regular engineer explained that the gauges for the outer tanks always read 5 gallons, regardless of the contents.

There are times when the wing in ground effect is not helpful.

The Boeing 747 is a remarkable aeroplane, still in production nearly 50 years after its first flight. The pilots find it a lovely aeroplane to fly, with crisp controls and a 60° per second roll rate. Not that they get much opportunity to enjoy its manoeuvrability. The passengers demand the smoothness of ride delivered by the wide range of automation which controls all its systems. Soon after take-off, the triple auto-pilots are engaged and they fly the aeroplane for the rest of the journey, which could be up to 14 hours.

Back at base, he learned that the fuelling had been done by a mechanic who had started just the day before. The regular engineer explained that the gauges for the outer tanks always read 5 gallons, regardless of the contents.

There are times when the wing in ground effect is not helpful.

The Boeing 747 is a remarkable aeroplane, still in production nearly 50 years after its first flight. The pilots find it a lovely aeroplane to fly, with crisp controls and a 60° per second roll rate. Not that they get much opportunity to enjoy its manoeuvrability. The passengers demand the smoothness of ride delivered by the wide range of automation which controls all its systems. Soon after take-off, the triple auto-pilots are engaged and they fly the aeroplane for the rest of the journey, which could be up to 14 hours.

On the approach to land, the non-landing pilot ensures that the 747 is established on the approach at 160 knots, wheels and flaps down and landing checks completed. The autopilots could complete the landing, indeed, there is a requirement that a minimum number of autolands should be carried out to retain certification of the systems, but it seldom happens this way. At about 1000 ft, the landing pilot switches off the autopilots and takes control. He might, or might not, have to correct for drift, but there is one correction which is always needed.

Manual decision height is 200 feet – about one span width - above the threshold. It is just at this point where the ground effect begins to be felt. In this case, the extra lift it offers is a benefit which is definitely not wanted and the pilot discards it with a small, but deliberate forward movement of the controls to keep the 747 on its correct, precise angle of descent.

Manual decision height is 200 feet – about one span width - above the threshold. It is just at this point where the ground effect begins to be felt. In this case, the extra lift it offers is a benefit which is definitely not wanted and the pilot discards it with a small, but deliberate forward movement of the controls to keep the 747 on its correct, precise angle of descent.

Building the ground effect into a flight plan is unusual but there is one place where it happens on a regular basis. The shortest flight from the US mainland to Hawaii is 2,100 miles. It’s a well-trodden route for ferry pilots delivering small aeroplanes to their new owners in Hawaii, Australia or other Far Eastern countries. Almost all need to supplement their normal fuel, usually sending the passenger seats ahead by air cargo and filling the space with a long-range tank, or adding Dolly Partons – bulbous tip tanks. This can extend their endurance up to twenty hours but makes them rather overweight.

The FAA issues special Supplemental Certificates which allow them to take off as much as 25% over gross. They also are given permission to fly under the Golden Gate bridge. So they leave the long runway of an airfield in the Bay area and, although there’s a 220 ft gap between the bridge deck and the sea, they stay low and head out over the Pacific using the ground effect until they have burnt off enough of the overload to climb to cruising height.