Frank T Courtney (1894 – 1982) (Sept 2021)

Frank Courtney had a long and successful career as a test pilot in both Europe and in America and was highly regarded in the industry. He was involved in many of the significant developments in aviation and yet is surprisingly little known.

He had an unusual family background. Born in London to a middle-class family he was just five years old when his parents separated. He and his two younger brothers were put into a boarding nursery. Subsequently, they grew up in a succession of boarding schools. It was an expensive way to raise children and Frank’s education was cut short and he was left with no qualifications, offset by a good deal of self-reliance. Some influence from a relative found him a job as a trainee in a bank in Paris. He regarded the prospects of high responsibility and solid security as being ‘deadly dull’. He was determined to find something else to do with his life. All the stories he had read about exciting lives had been of men who had travelled the seven seas on voyages of discovery. Yet, even there, opportunities for exploration were disappearing. One day, Frank’s ambitions were raised to what he referred to as the eighth sea – the sky.

He had an unusual family background. Born in London to a middle-class family he was just five years old when his parents separated. He and his two younger brothers were put into a boarding nursery. Subsequently, they grew up in a succession of boarding schools. It was an expensive way to raise children and Frank’s education was cut short and he was left with no qualifications, offset by a good deal of self-reliance. Some influence from a relative found him a job as a trainee in a bank in Paris. He regarded the prospects of high responsibility and solid security as being ‘deadly dull’. He was determined to find something else to do with his life. All the stories he had read about exciting lives had been of men who had travelled the seven seas on voyages of discovery. Yet, even there, opportunities for exploration were disappearing. One day, Frank’s ambitions were raised to what he referred to as the eighth sea – the sky.

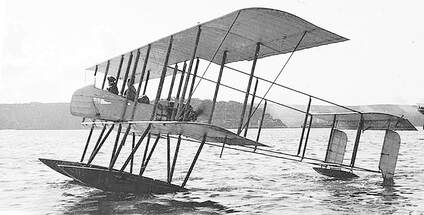

It was on a Sunday in 1913 when Frank was out for an afternoon stroll by the Seine that he came across a flying machine, floating on the river. It was an Henri Farman biplane. He had never been close to an aeroplane before and he was fascinated.

The mechanic who was looking after the aeroplane was sufficiently bored to respond to Frank’s many questions. He was even allowed to climb into the cockpit where he was shown how the controls worked.

The mechanic who was looking after the aeroplane was sufficiently bored to respond to Frank’s many questions. He was even allowed to climb into the cockpit where he was shown how the controls worked.

Frank had found what he wanted to do. He read everything he could about aviation – and there was a lot going on in France at the time – and he made a list of the names of anyone who was connected in any way with building or flying aeroplanes. He prepared a letter in which he cunningly suggested some kind of an improvement to existing aeroplanes and, of course, pointed out that he would like the opportunity to come and work on it. There were one or two polite but uninterested replies, the majority elicited no response. Frank spread his net further afield until finally he had a reply which did not tell him to go away.

In the letter to Claude Grahame-White at his factory in Hendon he had enthused about huge aeroplanes which would carry twenty passengers at 100 mph. Grahame-White was amused by this. It so happened that he was building the first step on the road to Frank’s vision, a biplane which would carry five people at 55 mph. He said that Frank’s enthusiasm might be useful and he offered him an unpaid apprenticeship. The normal apprenticeship fees would be waived.

A few weeks later, Frank walked into the little office at Hendon. G-W had to be reminded who he was – and admitted later that he was not impressed by the ‘tall, weedy, round shouldered youth, squinting through his glasses’. The gruff office manager gave him the usual greeting. He would be working on the job in all the departments and if he didn’t learn fast and work hard he wouldn’t be there long. And did he realise that apprentices are not paid any wages? At 6.30 the following morning, in his clean new overalls, he reported to the metal-shop foreman. The dark shed, cluttered with greasy machinery and piles of strips of different metals was far removed from where Frank expected to launch on his glittering new career on the great eighth sea.

Grahame-White owned the airfield and as well as his factory there were several other buildings rented out to some who were building their own aeroplanes or making parts to be sold to other builders. G-W also ran a school where rich young men would come to learn to fly one of the delicate biplanes to take part in this new exciting sport. The workers in the factory probably spent as much time repairing the school machines after crashes as they did in building new aeroplanes.

Other pilots brought their machines to Hendon and often sought the help of the apprentices for minor repairs, a practice which G-W encouraged. They weren’t paid. The rewards was often a decent lunch or dinner in a restaurant. The best reward was a flight, particularly if there was a chance to operate the controls. After these brief tasting moments Frank naturally longed to learn to fly, but the prohibitive fee of £75 was an insurmountable block. He talked about it so much whenever he found G-W or the manager in a good mood that, to shut him up, they said they would train him if he could produce £50, quite confident that it was way beyond the reach of an unpaid and almost penniless apprentice.

Frank soon learned that none of his well-heeled relatives would have anything to do with such a risky business as flying. There were too many stories in the newspapers about people regularly dying in plane crashes. As a last resort he approached the family lawyer. Somewhere in the family finances he knew there was a small fund being built up which would one day be his. Could he please, possibly, borrow £50 from that? The frosty face softened. The lawyer wished that he could be young again and Frank left clutching £50.

In the letter to Claude Grahame-White at his factory in Hendon he had enthused about huge aeroplanes which would carry twenty passengers at 100 mph. Grahame-White was amused by this. It so happened that he was building the first step on the road to Frank’s vision, a biplane which would carry five people at 55 mph. He said that Frank’s enthusiasm might be useful and he offered him an unpaid apprenticeship. The normal apprenticeship fees would be waived.

A few weeks later, Frank walked into the little office at Hendon. G-W had to be reminded who he was – and admitted later that he was not impressed by the ‘tall, weedy, round shouldered youth, squinting through his glasses’. The gruff office manager gave him the usual greeting. He would be working on the job in all the departments and if he didn’t learn fast and work hard he wouldn’t be there long. And did he realise that apprentices are not paid any wages? At 6.30 the following morning, in his clean new overalls, he reported to the metal-shop foreman. The dark shed, cluttered with greasy machinery and piles of strips of different metals was far removed from where Frank expected to launch on his glittering new career on the great eighth sea.

Grahame-White owned the airfield and as well as his factory there were several other buildings rented out to some who were building their own aeroplanes or making parts to be sold to other builders. G-W also ran a school where rich young men would come to learn to fly one of the delicate biplanes to take part in this new exciting sport. The workers in the factory probably spent as much time repairing the school machines after crashes as they did in building new aeroplanes.

Other pilots brought their machines to Hendon and often sought the help of the apprentices for minor repairs, a practice which G-W encouraged. They weren’t paid. The rewards was often a decent lunch or dinner in a restaurant. The best reward was a flight, particularly if there was a chance to operate the controls. After these brief tasting moments Frank naturally longed to learn to fly, but the prohibitive fee of £75 was an insurmountable block. He talked about it so much whenever he found G-W or the manager in a good mood that, to shut him up, they said they would train him if he could produce £50, quite confident that it was way beyond the reach of an unpaid and almost penniless apprentice.

Frank soon learned that none of his well-heeled relatives would have anything to do with such a risky business as flying. There were too many stories in the newspapers about people regularly dying in plane crashes. As a last resort he approached the family lawyer. Somewhere in the family finances he knew there was a small fund being built up which would one day be his. Could he please, possibly, borrow £50 from that? The frosty face softened. The lawyer wished that he could be young again and Frank left clutching £50.

A few days later, he joined the other trainees at the pre-dawn meeting when the machines were pulled out of the hangars. Training usually started before sun up and ended when any breeze rose. After learning to handle the temperamental engine there were three stages, ‘dual straights’, ‘solo straights’ and ‘circuits’. The instructor was present only for the first stage, a low level hop and landing before reaching the far hedge. Solo straights assumed a reasonable level of competence and finally the pupil would be sent off solo to do ‘circuits’ even though no instruction in turning had been given.

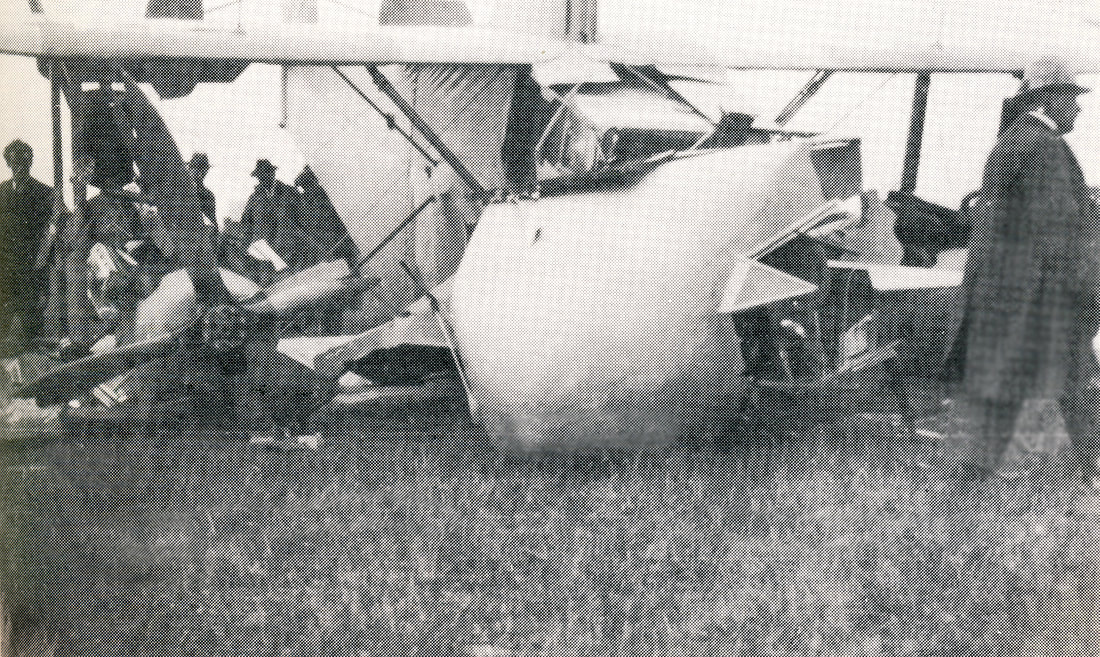

Accidents were frequent and kept G–W’s mechanics busy. This is not an accident of Frank’s. Here he is, on the left, and smartly dressed in a suit. He must have been a trainee pilot that day and not in his usual garb of overalls.

With his previous experience of briefly ‘flying’ other peoples’ aeroplanes he was a good student and progressed rapidly. He took care that it was too rapid. He was well aware that as soon as he got his ‘ticket’ there would be no more flying for him.

Then, suddenly, everything changed. On 4th August, 1914, Britain was at war with Germany. There was a rush to join the Royal Flying Corps or the Royal Naval Air Service to take part in the great adventure before the war petered out, as many thought it would. Frank volunteered for both. A few days later, he got a telegram telling him to report to RFC HQ at Farnborough, There he was interviewed by the new Commanding Officer, Major Hugh Trenchard. The interview was brief. ‘Don’t try to tell me you can fly with those glasses on. Get out.’

Back at Hendon, all was chaos. Half the men had gone – G-W himself was in RNAS uniform with the rank of Flight Commander - and many army and navy engineers were arriving with plans for the factory to produce B.E 2Cs. Frank managed to fit in the delayed flying tests to qualify for his ticket in case it would prove useful. At first, it didn’t. Now an experienced (comparatively) engineer he was posted as a service engineer to visit military stations which were having problems maintaining the aeroplanes which had been allocated to them. On another visit to Farnborough a Sergeant told him that all his good engineers had been sent to France and the new recruits were useless. If Frank joined up he’d be promoted in no time. Frank told him about Trenchard’s reaction to his glasses. ’Trenchard’s in France now. Ashmore (the new CO) will take you’.

He did. Frank became No. 28941 2nd Class Air Mechanic Courtney. After a couple of weeks square bashing and learning how and when to salute he was posted to a squadron which was busy preparing its aeroplanes for war. In the early months of 1915 a number of crashes and a little pneumonia rendered the squadron short of pilots. Frank was called to see the CO, Major Philip Joubert. Was it true that he had a pilot’s licence? With only a little gilding of the lily in terms of hours and types flown he was told to take a test flight with one of the Sergeant Pilots.

A favourable report put Frank on the list of the Squadron’s reserve pilots. Then, since anyone who could fly was supposed to be able to instruct, Frank volunteered to give training at the less popular hours like early mornings and weekends. His usual ‘students’ were young officers newly arrived from flying school who needed more experience. After a few weeks officialdom took notice and Frank was allowed to wear RFC wings and even given flying pay. RFC history shows that he was one of only two low-ranking Air Mechanics who flew as qualified pilots.

Accidents were frequent and kept G–W’s mechanics busy. This is not an accident of Frank’s. Here he is, on the left, and smartly dressed in a suit. He must have been a trainee pilot that day and not in his usual garb of overalls.

With his previous experience of briefly ‘flying’ other peoples’ aeroplanes he was a good student and progressed rapidly. He took care that it was too rapid. He was well aware that as soon as he got his ‘ticket’ there would be no more flying for him.

Then, suddenly, everything changed. On 4th August, 1914, Britain was at war with Germany. There was a rush to join the Royal Flying Corps or the Royal Naval Air Service to take part in the great adventure before the war petered out, as many thought it would. Frank volunteered for both. A few days later, he got a telegram telling him to report to RFC HQ at Farnborough, There he was interviewed by the new Commanding Officer, Major Hugh Trenchard. The interview was brief. ‘Don’t try to tell me you can fly with those glasses on. Get out.’

Back at Hendon, all was chaos. Half the men had gone – G-W himself was in RNAS uniform with the rank of Flight Commander - and many army and navy engineers were arriving with plans for the factory to produce B.E 2Cs. Frank managed to fit in the delayed flying tests to qualify for his ticket in case it would prove useful. At first, it didn’t. Now an experienced (comparatively) engineer he was posted as a service engineer to visit military stations which were having problems maintaining the aeroplanes which had been allocated to them. On another visit to Farnborough a Sergeant told him that all his good engineers had been sent to France and the new recruits were useless. If Frank joined up he’d be promoted in no time. Frank told him about Trenchard’s reaction to his glasses. ’Trenchard’s in France now. Ashmore (the new CO) will take you’.

He did. Frank became No. 28941 2nd Class Air Mechanic Courtney. After a couple of weeks square bashing and learning how and when to salute he was posted to a squadron which was busy preparing its aeroplanes for war. In the early months of 1915 a number of crashes and a little pneumonia rendered the squadron short of pilots. Frank was called to see the CO, Major Philip Joubert. Was it true that he had a pilot’s licence? With only a little gilding of the lily in terms of hours and types flown he was told to take a test flight with one of the Sergeant Pilots.

A favourable report put Frank on the list of the Squadron’s reserve pilots. Then, since anyone who could fly was supposed to be able to instruct, Frank volunteered to give training at the less popular hours like early mornings and weekends. His usual ‘students’ were young officers newly arrived from flying school who needed more experience. After a few weeks officialdom took notice and Frank was allowed to wear RFC wings and even given flying pay. RFC history shows that he was one of only two low-ranking Air Mechanics who flew as qualified pilots.

His usual mount was the Maurice Farman Shorthorn, the type used at flying schools. Visitors to the squadron came in other types and some happened to be friends from Frank’s Hendon days. They let him fly their aeroplanes and he soon built up a wide range of types in his logbook. So when the squadron was lent a Martinsyde Scout it was easy for Frank to persuade his Captain to let him fly it.

The Scout was a supposedly fast but unstable little machine which no-one liked flying. Frank struggled to master it. He wanted to try to loop it. At the time it was an RFC ruling that looping required official permission. The CO told him he had to climb to 3000 ft before his loop. This gave time for quite a crowd of spectators to gather.

The Scout was fitted with a powerful rotary engine and displayed all the gyroscopic reactions that were later used to effect in the handling of the Sopwith Camel. Frank dived to pick up speed for his loop. He pulled back on the stick and the Scout shot off to the right. He had no idea what manoeuvres he performed but he was down to 1000 ft before he got the horizon level again. He climbed back to 3000 ft and tried again with similar results. He gave up and landed. The spectators had clearly enjoyed the display. Most were laughing and some applauding. Word had got around that he had learned stunt flying at Hendon and had not given a display before because of his low rank. He was quite relieved that he didn’t get another flight in the ‘Tinsyde’ because one of the officers crashed it on landing.

A couple of weeks later, Frank was posted, without any explanation, to Gosport for a special ‘monoplane course’. Two years before, there had been a spate of accidents involving monoplanes. The politicians reacted by banning all monoplanes. It was immediately realised that the ban was illogical and unproductive. It was lifted six months later. But the prejudice against monoplanes lingered and throughout the war only one British monoplane, the Bristol M.1C, was ordered by the military. Even then, they were all sent out to secondary theatres of war in the Middle East. However, the RFC was acquiring aeroplanes from wherever they could find them and several French types were monoplanes. Hence the need for the ‘special’ training.

A couple of weeks later, Frank was posted, without any explanation, to Gosport for a special ‘monoplane course’. Two years before, there had been a spate of accidents involving monoplanes. The politicians reacted by banning all monoplanes. It was immediately realised that the ban was illogical and unproductive. It was lifted six months later. But the prejudice against monoplanes lingered and throughout the war only one British monoplane, the Bristol M.1C, was ordered by the military. Even then, they were all sent out to secondary theatres of war in the Middle East. However, the RFC was acquiring aeroplanes from wherever they could find them and several French types were monoplanes. Hence the need for the ‘special’ training.

the end of the course Frank was posted back to Farnborough. His first job was to take an ancient Bleriot to Netheravon. It was a Bleriot XI, like the one which flew the first cross-Channel flight in 1909.

Frank experienced all of its foibles. It was prone to dropping a wing, either wing. Sometimes it was nose heavy, sometimes tail heavy and the controls reacted differently as the airspeed increased. Added to this was the unreliable engine which often spluttered and occasionally stopped. Two days and three forced landings later, Frank completed the 60 mile journey.

Frank experienced all of its foibles. It was prone to dropping a wing, either wing. Sometimes it was nose heavy, sometimes tail heavy and the controls reacted differently as the airspeed increased. Added to this was the unreliable engine which often spluttered and occasionally stopped. Two days and three forced landings later, Frank completed the 60 mile journey.

There he was asked by the Netheravon CO to take another monoplane to Hendon. It was assumed that if he’d flown in on a monoplane then he could fly the Morane. Frank made no comment on that. For some time he had wanted to fly this fast and manoeuvrable monoplane. It had a reputation of being exciting but difficult to fly.

The Morane had no fixed tail plane, the whole surface moved making the elevator control very light and very sensitive. In contrast, rolling was controlled by wing warping which was very heavy, particularly at higher speeds.

And the need for skilful handling persisted to the end of the flight. The clean lines gave it a very flat glide making landings tricky. Frank did find it difficult to fly. He made maximum use of the flight to Hendon to practise the handling and even aerobatics unobserved by critical spectators. To confirm his growing competence and confidence his promotion to Corporal appeared in orders.

The Morane had no fixed tail plane, the whole surface moved making the elevator control very light and very sensitive. In contrast, rolling was controlled by wing warping which was very heavy, particularly at higher speeds.

And the need for skilful handling persisted to the end of the flight. The clean lines gave it a very flat glide making landings tricky. Frank did find it difficult to fly. He made maximum use of the flight to Hendon to practise the handling and even aerobatics unobserved by critical spectators. To confirm his growing competence and confidence his promotion to Corporal appeared in orders.

Frank desperately wanted to go to France where the real action was. He was reluctant to apply. He had heard of Sergeant Pilots being posted to front line squadrons but no Corporal plots. And he was sure that having to wear glasses would disqualify him. So he was delighted with his next assignment. He was ordered to collect one of the new Avro 504s from Brooklands and take it to St Omer. He asked his CO if it meant he could remain in France. ‘Of course’, was the answer. ‘You’re posted overseas’.

Crossing the Channel was still a hazardous undertaking for new pilots who usually navigated by learning the local landmarks. It was not uncommon for pilots to fail to reach France. Several had landed in Essex to find out where they were. They had ignored their compass and confused the Thames estuary with the Channel. Many just disappeared and were lost at sea. The authorities set up one of the first ground aids to navigation. Two large white crosses were cut in the chalky fields near Folkestone, a couple of miles apart. If a pilot couldn’t see both, then visibility was too bad to attempt the crossing. When he could see both, he would fly a straight course between them, correcting for drift, then carefully note his compass indication. Whatever it said, he should stick to it until the cliffs at Cap Gris-Nez came into view.

Frank didn’t need the crosses. On a fine spring day, he could already see France whilst still over Kent. After a pleasant crossing, he found St Omer and landed, handing over the Avro to the RFC’s Aircraft Park. He hurried to the HQ building to report to the CO and find out what was going to happen to him. The first shock was that the CO was none other than Lt. Col. Trenchard. Would he remember their first meeting? Should he take off his glasses? In Trenchard’s office, Frank’s file lay opened on the desk. Trenchard was smiling. ‘So’ he boomed. ‘You managed to get here, glasses and all’.

Frank found that he was promoted to Sergeant and would be posted to 3 Squadron to fly Moranes. These Moranes were a modified version of the kind Frank had flown in England. They had an extra seat for an observer and the wing was raised to a parasol position to give the crew a better view. The 80 hp Gnome rotary had to cope with the extra weight so it meant some loss of performance but the flying characteristics were the same.

3 Squadron were based at Auchel, a little village 12 miles behind the lines. Frank needed no introduction to his flight commander, Capt. T. O’Brien Hubbard. ‘Mother’ Hubbard had been a frequent visitor to Hendon before the war and Frank had flown in his Henri Farman biplane. Hubbard asked Sgt Jim McCudden, in charge of the engine shop, to show Frank around. (McCudden had applied for pilot training but was such a good engineer that his CO didn’t want to lose him and his application had been turned down. He occasionally flew in 3 Sqn. as an observer, armed with a standard .303 file, and did so well that he was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Only then did he get his pilot training. He went on to become one of the War’s great ‘aces’, shooting down 57 enemy planes and winning the VC).

Frank didn’t need the crosses. On a fine spring day, he could already see France whilst still over Kent. After a pleasant crossing, he found St Omer and landed, handing over the Avro to the RFC’s Aircraft Park. He hurried to the HQ building to report to the CO and find out what was going to happen to him. The first shock was that the CO was none other than Lt. Col. Trenchard. Would he remember their first meeting? Should he take off his glasses? In Trenchard’s office, Frank’s file lay opened on the desk. Trenchard was smiling. ‘So’ he boomed. ‘You managed to get here, glasses and all’.

Frank found that he was promoted to Sergeant and would be posted to 3 Squadron to fly Moranes. These Moranes were a modified version of the kind Frank had flown in England. They had an extra seat for an observer and the wing was raised to a parasol position to give the crew a better view. The 80 hp Gnome rotary had to cope with the extra weight so it meant some loss of performance but the flying characteristics were the same.

3 Squadron were based at Auchel, a little village 12 miles behind the lines. Frank needed no introduction to his flight commander, Capt. T. O’Brien Hubbard. ‘Mother’ Hubbard had been a frequent visitor to Hendon before the war and Frank had flown in his Henri Farman biplane. Hubbard asked Sgt Jim McCudden, in charge of the engine shop, to show Frank around. (McCudden had applied for pilot training but was such a good engineer that his CO didn’t want to lose him and his application had been turned down. He occasionally flew in 3 Sqn. as an observer, armed with a standard .303 file, and did so well that he was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Only then did he get his pilot training. He went on to become one of the War’s great ‘aces’, shooting down 57 enemy planes and winning the VC).

Frank was given his own machine, somewhat dented and battle-scarred, but the first aeroplane he could call his own. Not only that, he was heavily involved in the war in the air. He had arrived where he wanted to be.

Next morning he was given a map and told to familiarise himself with the landscape but not to cross the lines. From 3000 ft he was surprized by the number of zig-zagging trenches running in all directions between the shell holes. He was trying to pick out something that looked like the front line when a burst of black smoke appeared ahead of him. He heard the crash of the shell burst and saw little triangles of fabric flapping on his right wing. He dived towards the west and two more black bursts followed the Morane. When he landed he expected a reprimand for crossing the line but Hubbard seemed amused. ‘Now that you’ve met Archie (German AA fire) you can take the long reconnaissance this afternoon’. He was to fly with Lt. Selby, an experienced observer.

They took off and flew north, climbing to 6,000 ft before crossing the lines and turning to a long sweep to the south. A heavy haze had developed and they could see little of the ground but they flew on. By the time they turned for home it seemed that they had been invisible to the Germans because there had been no sign of any AA fire. Suddenly bursts of smoke surrounded the Morane. The smoke was white. This meant they were being fire on by Allied guns. The shooting was accurate and holes appeared in the fabric. Then Frank smelled fuel and felt it trickling on his leg. In the days before parachutes the airman’s greatest fear was fire in the air. Frank promptly switched off the engine, turned into a tight descending spiral to get down quickly and looked for somewhere to land.

Happily, a suitable field presented itself and the Morane rolled to a stop. Selby and Frank jumped out and exchanged views on idiot gunners. Two cars rushed up and soldiers in blue climbed out. A French officer vaulted the gate with revolver drawn intent on capturing airmen and aeroplane. Then he saw the markings on the plane. His apology began in the field and went on through an expansive and well-lubricated dinner at the Battery HQ.

Next morning he was given a map and told to familiarise himself with the landscape but not to cross the lines. From 3000 ft he was surprized by the number of zig-zagging trenches running in all directions between the shell holes. He was trying to pick out something that looked like the front line when a burst of black smoke appeared ahead of him. He heard the crash of the shell burst and saw little triangles of fabric flapping on his right wing. He dived towards the west and two more black bursts followed the Morane. When he landed he expected a reprimand for crossing the line but Hubbard seemed amused. ‘Now that you’ve met Archie (German AA fire) you can take the long reconnaissance this afternoon’. He was to fly with Lt. Selby, an experienced observer.

They took off and flew north, climbing to 6,000 ft before crossing the lines and turning to a long sweep to the south. A heavy haze had developed and they could see little of the ground but they flew on. By the time they turned for home it seemed that they had been invisible to the Germans because there had been no sign of any AA fire. Suddenly bursts of smoke surrounded the Morane. The smoke was white. This meant they were being fire on by Allied guns. The shooting was accurate and holes appeared in the fabric. Then Frank smelled fuel and felt it trickling on his leg. In the days before parachutes the airman’s greatest fear was fire in the air. Frank promptly switched off the engine, turned into a tight descending spiral to get down quickly and looked for somewhere to land.

Happily, a suitable field presented itself and the Morane rolled to a stop. Selby and Frank jumped out and exchanged views on idiot gunners. Two cars rushed up and soldiers in blue climbed out. A French officer vaulted the gate with revolver drawn intent on capturing airmen and aeroplane. Then he saw the markings on the plane. His apology began in the field and went on through an expansive and well-lubricated dinner at the Battery HQ.

When he was being driven back to Auchel in the squadron transport Frank was sober enough to reflect on his unusually eventful first day with 3 Squadron. He had been overwhelmed by such a wide range of new experiences, all overlain by the prospect of being wounded or killed, by the enemy, by the mistaken action of his ‘friends’, by his own unsuitable and/or unreliable equipment or just by the number of opportunities for bad luck to raise its ugly head. He had much to learn before he was a competent and effective war pilot.

He might have been the lowest ranking and newest pilot of 3 Squadron but Frank was lucky in having joined after a workable method of artillery observation had evolved. Communication with the battery was key and the early days of shuttling between battery and target to drop messages in streamered bags and reading the battery’s patterns of white signal strips had gone. Now they had radio. The first sets were so heavy that the observer had to be left on the ground. By mid 1915, they were lighter and engines were more powerful. The observer could transmit coded messages to the battery from nearly 12 miles away, interference and reliability of the set allowing. The radio was not a receiver so an initial reading of the signal strips was still necessary.

On their cumbersome duty the Moranes of 3 Squadron (and more numerous BE 2Cs of other units) cruised over Hunland at a stately 65 mph, frequently harassed by Archie and trying to ignore the occasional wobbling Allied shell on its way to its target. Often the observer shouted ‘Lower’ into the pilot’s ear allowing machine guns and rifles to join in the assault all intended to bring their flight and their lives to an end. They often met their German equivalent spotting for the enemy’s guns. They usually ignored each other or, when close enough even wave an ironic greeting. If in an aggressive mood, they might circle and take pot shots at each other with rifles or pistols. This routine was soon to change.

Frank’s day started well. He was told that he had been recommended for a commission and that HQ had approved. He would soon be a 2nd Lieutenant. For his patrol he had been paired with Sgt. George Thornton. They had toyed with the idea of attacking a German kite balloon if they came near one. Thornton loaded a number of grenades into his cockpit. Their plan was to climb higher than the balloon and cruise past it as if they were going elsewhere. Then, at the last minute, Frank would turn back and dive on the balloon. George would launch his grenades and the balloon would blow up.

It didn’t quite work like that. They found a balloon and turned into the attack without any reaction from Archie. Though Frank was diving steeply he didn’t seem to be getting any closer. It took some time to realise that the balloon was rapidly being pulled down. It was almost on the ground when all the machine guns round about opened up. Frank fled to the east knowing that, between him and the front were hundreds of other machine guns ready to attack any low flying aeroplane. He climbed to 6,000 ft before turning west. He settled on a straight course for home. Almost at once a black burst appeared just ahead and above. A second shell shook the Morane and Frank felt ‘a hundred hammers’ hitting him in the neck and shoulders. Something trickled down his back. Fabric was flapping and wires were slack but the controls still worked. Behind him, Thornton was cursing and bleeding but shouted that he was alright. Then he said ‘Something coming up behind. Looks like that German Morane’.

For some weeks there had been rumours that the Germans had built a copy of the single seat Morane and Frank had seen one in the distance diving on a BE and swooping up to attack from under its tail. Now the ‘Morane’ approached and Thornton shouted ‘It’s diving’. Frank hoped he had got the timing right when he swung sharply to the right. He was surprised to hear the noisy clatter of a machine gun at close quarters and even the crackle of the passing bullets. He saw the black Maltese crosses on the wings of the German as it climbed past him. It did a curious turn and dived to attack again and again. In constant pain from the wound in his back and with a buzzing brain Frank twisted and turned, concerned by how much his damaged machine could stand the stressful manoeuvring.

At last a burst of bullets stuck the cockpit. Frank heard and felt them striking the steel plate on his seat, his legs were hit and his feet knocked off the rudder bar – and the engine stopped. He pushed the nose down though he hardly expected to be able to do a forced landing before the killer blow. Below them was a maze of shell holes, trenches and barbed wire. The ‘landing’ was a blur of sliding into obstacles and posts with pieces being torn off the plane. But they finished upright. They were hauled from the wreckage by a group of Scottish soldiers who took them to a dugout. Someone stuck a needle into Frank’s arm and he was carted off to a field hospital. Thornton had been lucky. He was a mass of bloody cuts and punctures, none of them serious and needing only generous application of sticking plasters to be able to go back to the squadron.

Frank was visited in hospital by ‘Mother’ Hubbard and his observer, Charles Portal (later to become Marshal of the RAF Viscount Portal of Hungerford). They showed him a rough translation of the German daily communiqué. It stated that their Morane had been shot down by a Leutnant Max Inglemann.

After the war Frank found himself in a unique position to be able to uncover the story behind the ‘Fokker Scourge’ as it became known. He first met Fokker in England in 1921, they became friends and later worked together on several projects. He also had many contacts with Morane-Saulnier from the days when Grahame White used to make Moranes under licence. The idea to have a single seater with the pilot firing a fixed gun originated with Raymond Saulnier. There was already a Swiss patent for an interrupter gear but Saulnier designed his own. His aeroplane was ready for testing in April 1914, four months before war broke out. It consistently failed to work. Much later, it was found that the fault lay entirely with the gun belts and ammunition supplied by the French army. It was all defective ammunition that should have been scrapped but the Army thought it would be good enough for simple tests. The frustrated Saulnier thought he could at least get the flying tests of his aeroplane done and fitted simple triangular steel blocks on the propeller blades to deflect any mis-timed bullets. Meanwhile, the Army lost all interest in the scheme which they didn’t really want so the project was shelved.

On their cumbersome duty the Moranes of 3 Squadron (and more numerous BE 2Cs of other units) cruised over Hunland at a stately 65 mph, frequently harassed by Archie and trying to ignore the occasional wobbling Allied shell on its way to its target. Often the observer shouted ‘Lower’ into the pilot’s ear allowing machine guns and rifles to join in the assault all intended to bring their flight and their lives to an end. They often met their German equivalent spotting for the enemy’s guns. They usually ignored each other or, when close enough even wave an ironic greeting. If in an aggressive mood, they might circle and take pot shots at each other with rifles or pistols. This routine was soon to change.

Frank’s day started well. He was told that he had been recommended for a commission and that HQ had approved. He would soon be a 2nd Lieutenant. For his patrol he had been paired with Sgt. George Thornton. They had toyed with the idea of attacking a German kite balloon if they came near one. Thornton loaded a number of grenades into his cockpit. Their plan was to climb higher than the balloon and cruise past it as if they were going elsewhere. Then, at the last minute, Frank would turn back and dive on the balloon. George would launch his grenades and the balloon would blow up.

It didn’t quite work like that. They found a balloon and turned into the attack without any reaction from Archie. Though Frank was diving steeply he didn’t seem to be getting any closer. It took some time to realise that the balloon was rapidly being pulled down. It was almost on the ground when all the machine guns round about opened up. Frank fled to the east knowing that, between him and the front were hundreds of other machine guns ready to attack any low flying aeroplane. He climbed to 6,000 ft before turning west. He settled on a straight course for home. Almost at once a black burst appeared just ahead and above. A second shell shook the Morane and Frank felt ‘a hundred hammers’ hitting him in the neck and shoulders. Something trickled down his back. Fabric was flapping and wires were slack but the controls still worked. Behind him, Thornton was cursing and bleeding but shouted that he was alright. Then he said ‘Something coming up behind. Looks like that German Morane’.

For some weeks there had been rumours that the Germans had built a copy of the single seat Morane and Frank had seen one in the distance diving on a BE and swooping up to attack from under its tail. Now the ‘Morane’ approached and Thornton shouted ‘It’s diving’. Frank hoped he had got the timing right when he swung sharply to the right. He was surprised to hear the noisy clatter of a machine gun at close quarters and even the crackle of the passing bullets. He saw the black Maltese crosses on the wings of the German as it climbed past him. It did a curious turn and dived to attack again and again. In constant pain from the wound in his back and with a buzzing brain Frank twisted and turned, concerned by how much his damaged machine could stand the stressful manoeuvring.

At last a burst of bullets stuck the cockpit. Frank heard and felt them striking the steel plate on his seat, his legs were hit and his feet knocked off the rudder bar – and the engine stopped. He pushed the nose down though he hardly expected to be able to do a forced landing before the killer blow. Below them was a maze of shell holes, trenches and barbed wire. The ‘landing’ was a blur of sliding into obstacles and posts with pieces being torn off the plane. But they finished upright. They were hauled from the wreckage by a group of Scottish soldiers who took them to a dugout. Someone stuck a needle into Frank’s arm and he was carted off to a field hospital. Thornton had been lucky. He was a mass of bloody cuts and punctures, none of them serious and needing only generous application of sticking plasters to be able to go back to the squadron.

Frank was visited in hospital by ‘Mother’ Hubbard and his observer, Charles Portal (later to become Marshal of the RAF Viscount Portal of Hungerford). They showed him a rough translation of the German daily communiqué. It stated that their Morane had been shot down by a Leutnant Max Inglemann.

After the war Frank found himself in a unique position to be able to uncover the story behind the ‘Fokker Scourge’ as it became known. He first met Fokker in England in 1921, they became friends and later worked together on several projects. He also had many contacts with Morane-Saulnier from the days when Grahame White used to make Moranes under licence. The idea to have a single seater with the pilot firing a fixed gun originated with Raymond Saulnier. There was already a Swiss patent for an interrupter gear but Saulnier designed his own. His aeroplane was ready for testing in April 1914, four months before war broke out. It consistently failed to work. Much later, it was found that the fault lay entirely with the gun belts and ammunition supplied by the French army. It was all defective ammunition that should have been scrapped but the Army thought it would be good enough for simple tests. The frustrated Saulnier thought he could at least get the flying tests of his aeroplane done and fitted simple triangular steel blocks on the propeller blades to deflect any mis-timed bullets. Meanwhile, the Army lost all interest in the scheme which they didn’t really want so the project was shelved.

A lucky bullet from a guard in the train he was shooting up shattered his fuel line. Garros and his Morane were captured. The Morane was taken to Berlin and displayed largely as an object of curiosity. The Army authorities were not much impressed. The steel blocks were deemed to be dangerous and there was still a widespread belief that no pilot could fly his plane and operated a machine gun at the same time. Anthony Fokker saw it differently. As an accomplished pilot he knew what an effective weapon it could be.

Later, Fokker was quite happy for the story to spread that the German generals had asked him to produce a fighter to rival the Garros machine and he had developed his childhood game of throwing stones through the whirling sails of windmills. What he actually did was to find that the captured Morane still had Saulnier’s abandoned interrupter gear fitted. It took one of his engineers a few days to modify it to fit German bullets.

Later, Fokker was quite happy for the story to spread that the German generals had asked him to produce a fighter to rival the Garros machine and he had developed his childhood game of throwing stones through the whirling sails of windmills. What he actually did was to find that the captured Morane still had Saulnier’s abandoned interrupter gear fitted. It took one of his engineers a few days to modify it to fit German bullets.

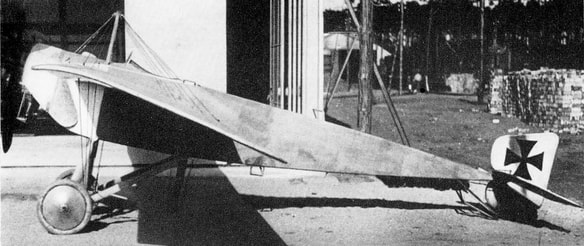

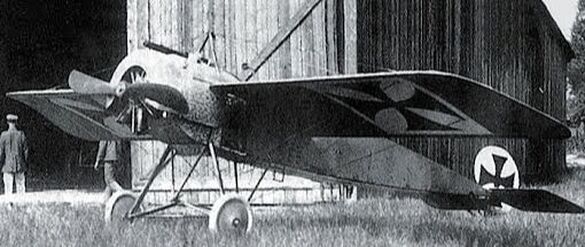

Getting the right aeroplane took a little longer – Fokker was no designer or engineer. He had long admired the monoplanes made by Bruno Hanuschke and his M.5 was almost right.

The Hanuschke

The Fokker

Fokker built an M.5, changing the tail, the undercarriage and other minor details. Fitted with a machine gun and the interrupter gear it emerged as the prototype of what became the Fokker E.1 Eindecker.

It was difficult to fly with poor lateral control and over sensitive elevator. They were issued in ones and two to individual units and only the best pilots flew them, people like Oswald Bölke and Max Immelmann, the man who shot down Frank Courtney.

Frank also had his own view on the famous Immelmann turn, often now interpreted as half a loop and half a roll at the top. Such a manoeuvre was impossible in an Eindecker. He had watched Immelmann pull up into a climbing turn and keep rolling steeply. As the Fokker lost speed Immelmann kicked the rudder to drop the nose into the next dive, completing a manoeuvre which the French would later call a Chandelle.

Frank had been shot down on 21st October, 1915 and was in hospital until January 1916. There followed a short period of confusion after it was found that Army records showed he had died on that October day. Eventually, order was restored, he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant and posted to the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough as a test pilot, the only one, he was surprised to learn, with any experience of war service.

Frank was lucky to arrive at Farnborough at the time when he did. Previously they had been concerned with ensuring that new types were flying well enough to enter service. Now they were beginning to do serious testing in all aspects of flying, including stalling, spinning and ‘extreme handling’ - aerobatics. Frank also did extensive testing with a range of gyroscopic instruments being developed as turn indicators and bombsights.

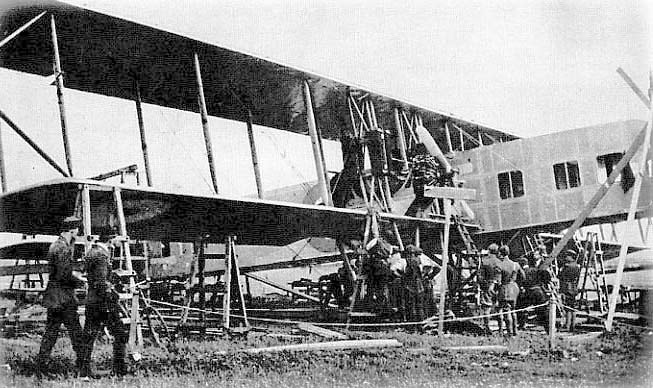

Most of his work was with aeroplanes that were already in production but he was once asked to do the first flight of a newly built type. Kennedy Aeroplanes had been set up by C J H Mackenzie-Kennedy who had, apparently, worked with Igor Sikorsky when he built his huge Murometz biplanes in 1913. Kennedy produced his own design, a giant bomber of 142 ft span. He had been promised financial support from the government, ‘once the machine had been flown by an RFC officer’. It was built by Fairey at Northolt, not in a factory – it was too big for any existing building - but in the open. Frank examined every aspect of it in a series of visits. It could be that he is one of the uniformed officers in the picture.

Frank also had his own view on the famous Immelmann turn, often now interpreted as half a loop and half a roll at the top. Such a manoeuvre was impossible in an Eindecker. He had watched Immelmann pull up into a climbing turn and keep rolling steeply. As the Fokker lost speed Immelmann kicked the rudder to drop the nose into the next dive, completing a manoeuvre which the French would later call a Chandelle.

Frank had been shot down on 21st October, 1915 and was in hospital until January 1916. There followed a short period of confusion after it was found that Army records showed he had died on that October day. Eventually, order was restored, he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant and posted to the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough as a test pilot, the only one, he was surprised to learn, with any experience of war service.

Frank was lucky to arrive at Farnborough at the time when he did. Previously they had been concerned with ensuring that new types were flying well enough to enter service. Now they were beginning to do serious testing in all aspects of flying, including stalling, spinning and ‘extreme handling’ - aerobatics. Frank also did extensive testing with a range of gyroscopic instruments being developed as turn indicators and bombsights.

Most of his work was with aeroplanes that were already in production but he was once asked to do the first flight of a newly built type. Kennedy Aeroplanes had been set up by C J H Mackenzie-Kennedy who had, apparently, worked with Igor Sikorsky when he built his huge Murometz biplanes in 1913. Kennedy produced his own design, a giant bomber of 142 ft span. He had been promised financial support from the government, ‘once the machine had been flown by an RFC officer’. It was built by Fairey at Northolt, not in a factory – it was too big for any existing building - but in the open. Frank examined every aspect of it in a series of visits. It could be that he is one of the uniformed officers in the picture.

On the day of the first flight, Frank approached it with caution. Its four 200 hp Salmson engines, two pull, two push, didn’t seem enough to get it off the ground. Yet it was a perfect day. A good breeze was blowing and the first part of the ‘runway’ sloped slightly down. Enclosed in the vast cabin, itself an unusual experience, he taxied to the far corner of the field. Acceleration seemed to be quite good and soon the rumbling of the wheels stopped. He was airborne. Then he reached the level ground and the rumbling resumed. The aeroplane ran into a patch of soft ground and though the engines were at full throttle it rolled to a stop. The track marks were examined and showed that the wheels had been off the ground for at least 100 yards. They weren’t sure about the tail skid. The argument went on for several years in the law courts whilst the abandoned Giant slowly disintegrated at its birthplace.

Despite the interest of his work Frank was keen to get back to flying in combat. His boss, the Superintendent, Mervyn O’Gorman told him he would not be released. He was good at his job and was considered to be a permanent member of the team.

He saw what might be a possible escape route. He was told to take an aeroplane which had been fitted with a new, more powerful engine to France and demonstrate it to General Trenchard at the RFC’s HQ. Another type which had been re-engined was the FE 2b. Frank had done all the tests on it after its 120 hp Beardmore engine had been replaced with a 250 hp RR Eagle. It became the FE 2d and 20 Squadron had just received them.

Despite the interest of his work Frank was keen to get back to flying in combat. His boss, the Superintendent, Mervyn O’Gorman told him he would not be released. He was good at his job and was considered to be a permanent member of the team.

He saw what might be a possible escape route. He was told to take an aeroplane which had been fitted with a new, more powerful engine to France and demonstrate it to General Trenchard at the RFC’s HQ. Another type which had been re-engined was the FE 2b. Frank had done all the tests on it after its 120 hp Beardmore engine had been replaced with a 250 hp RR Eagle. It became the FE 2d and 20 Squadron had just received them.

When he got to France Frank suggested to General Trenchard that he could be very useful in showing 20 squadron how to get the best out of their new machines. It was enough to trigger his immediate transfer.

It was odd that the Fee should be classed as a fighter. It was large, stable and slow and quite useless at stalking and chasing an enemy. However, if they were attacked they defended themselves well.

Frank was in a formation of five that was fallen on by nine Fokkers. The Fees broke formation and swarmed about, keeping in a tight group. Any Fokker approaching them would be facing fire from two, three, or more guns wielded by the brave gunners who stood without any harness in the front cockpits, hanging on to their guns. Within minutes, three Germans had been shot down. The rest fled. Frank was glad to be back in the war, though he felt that flying the Fee was a bit boring – rather like driving a tank.

Around Christmas 1916 an old friend from his Grahame White days flew in to see him. He was flying a Sopwith 1½ Strutter. He suggested that Frank should join him at 45 Squadron. They needed experienced pilots. Having flown a Strutter in England Frank thought it performed reasonably well. Its chief attraction for him was that it was the first RFC machine in service with a fixed gun firing through the propeller. He put in his application for a transfer to 45 Sqn.

He joined the squadron when it was at a small airfield several miles behind the front, recovering from two months of heavy losses. Strutters had been used by the RNAS, largely for reconnaissance and bombing but also as two-seat fighters. In mid 1916 the production run was diverted to the RFC to satisfy its need for more aircraft. At the same time a new – and so not yet reliable - type of interrupter gear was fitted and a Scarff ring added to the gunner’s cockpit. In theory, the all round vision and combination of two guns working together should have made them effective fighters.

Around Christmas 1916 an old friend from his Grahame White days flew in to see him. He was flying a Sopwith 1½ Strutter. He suggested that Frank should join him at 45 Squadron. They needed experienced pilots. Having flown a Strutter in England Frank thought it performed reasonably well. Its chief attraction for him was that it was the first RFC machine in service with a fixed gun firing through the propeller. He put in his application for a transfer to 45 Sqn.

He joined the squadron when it was at a small airfield several miles behind the front, recovering from two months of heavy losses. Strutters had been used by the RNAS, largely for reconnaissance and bombing but also as two-seat fighters. In mid 1916 the production run was diverted to the RFC to satisfy its need for more aircraft. At the same time a new – and so not yet reliable - type of interrupter gear was fitted and a Scarff ring added to the gunner’s cockpit. In theory, the all round vision and combination of two guns working together should have made them effective fighters.

In practice, co-operation between the crew was almost impossible. Separated by the large fuel tank the Navy needed for its long over water patrols, they tried to talk to each other by shouting over the engine noise into ‘Gosport tubes’, long flexible pipes. To add more weight and complication, the ‘Staff’ decided there was enough room for a camera to be fitted in the gunner’s cockpit.

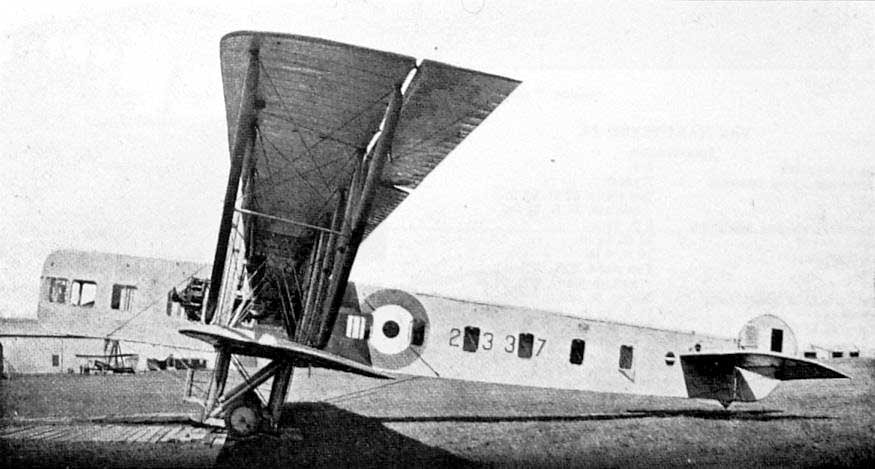

Frank’s 1½ Strutter

It was early 1917 and the new breed of German single-seat biplane fighters were appearing, Halberstadt, Albatros and Fokkers with more powerful engines and some with twin machine guns. The Strutters were completely outclassed. Their ‘fighting’ patrols were not offensive. They followed prescribed routes dictated by the targets to be photographed. The cynics described their job not as destroying the enemy, just making sure that the camera carrying machines got home. It was not unusual for a flight of five to lose two of its machines. Soon they were short of observers and asked the artillery for volunteers. It was then that they learned that they were known by the artillery as ‘the Suicide Club’.

In March, Frank was promoted to Captain and transferred as flight commander to 70 Squadron, also flying Sopwith Strutters. When he arrived he was told that six of his flight had gone out that morning and none had returned. The squadron was in constant need of aircrew and had no time to give any training to new pilots. One man arrived with just 4 hours solo flying in his logbook. He had never carried a passenger or fired a machine gun. Within weeks Frank was sent back to 45 Sqn. They were in greater need of flight commanders. Looking through the list of names to see which pilot should fly with which gunner he found that of the eighteen pilots who had gone into action two months before only he and two others remained.

They fought on through Bloody April (RFC losses – 245, German – 66). Somehow, Frank survived. He had aeroplanes shot up and lost gunners but all bullets missed him. A new squadron commander arrived, told not to fly in combat. He felt obliged to carry out just one flight, for morale purposes. He came home, severely wounded and retired to hospital. Frank was now the senior pilot and effectively running the squadron.

One day the Brigadier General arrived on a visit. It emerged he was there to find out why the squadron was performing so badly. Frank told him. His words had such impact that he was immediately sent home to England.

They fought on through Bloody April (RFC losses – 245, German – 66). Somehow, Frank survived. He had aeroplanes shot up and lost gunners but all bullets missed him. A new squadron commander arrived, told not to fly in combat. He felt obliged to carry out just one flight, for morale purposes. He came home, severely wounded and retired to hospital. Frank was now the senior pilot and effectively running the squadron.

One day the Brigadier General arrived on a visit. It emerged he was there to find out why the squadron was performing so badly. Frank told him. His words had such impact that he was immediately sent home to England.

After two weeks of leave, long overdue, he reported to RFC HQ in London. His encounter with the Brigadier was reviewed along with General Trenchard’s comments. Frank gathered that there would be no punishment but equally no hope of any more promotion. He was to be posted to a newly invented job, ‘Fighting Instructor’ to 18th Wing, eight training stations in and around London. He would have a free hand in devising and implementing methods of training new pilots for combat.

Someone in the upper echelons had realised that pilot training in the RFC was a shambles. Any pilot who was available between postings, medically unfit for combat, even newly qualified pilots could be sent to instruct pupils in whatever way they chose. Once a pupil could take off, turn and land he could be considered qualified. Most ‘instructors’ hated the job and referred to their pupils as ‘Huns’, because they killed more instructors than the enemy.

The campaigning of Major Smith-Barry finally had some effect and he was allowed to set up a School at Gosport specifically to train instructors. Frank posted himself there for a course.

The school flew in all kinds of weather, practised cross-wind, even downwind take offs and landings, taught aerobatics and emergency procedures and used several types of aeroplanes with different flying characteristics. Back with 18th Wing where Gosport-style training was being introduced Frank and two colleagues set up their own Special Instructors’ Flight at London Colney to train more instructors. At the same time, he was running his own ‘Fighting’ courses for pilots due for posting to France.

His workload increased when the Americans arrived. A squadron with a mix of newly trained and experienced pilots were based alongside Frank’s unit and shared the same messing facilities. The Americans needed aeroplanes and initially used any outdated types the RFC and RNAS didn’t need. They also had to learn RFC English for many aviation components and activities. Although it was not part of his job Frank became heavily involved. He built up a good relationship with Col. William Larned of the US Technical HQ who was trying to source aircraft and equipment from the British, French and Italians.

Other Allies arrived for training. Early in 1917 there had been a revolution in Russia. (It was in March on our Gregorian calendar. Russia still used the Julian calendar, so it was in February for them). It started with a strike by women, the army and navy joined them and the Czar abdicated. The new government decided to continue the war and sent a group of airmen to England for training. That was Frank’s job. The Russians had only odd scattered words of English. Luckily, a few spoke some French, in which Frank was fluent. They increased Frank’s workload – and the crash rate – and went home in time for the Bolshevik take-over of the government in October (November in Russia).

Meanwhile, Frank’s job enlarged. The nature of fighting was changing as new types were introduced and he was doing more experimental flying with new aeroplanes and new engines. A significant engine was the Liberty, designed in the US (to a great extent a development of the Mercedes III) and put into large scale production. His connections with the Americans was now official. He had meetings with many senior and influential people including Colonel Billy Mitchell who was to command all USAAC units in France. (Post-war he campaigned so vigorously to spend money or bombers rather than battleships that he was court-martialled). Col. Bill Larned had realised that, without the urgency of war, America had not yet developed the industrial, technical and political background needed now by the fighting forces and would be post war, by expanding commercial aviation. He had plans to set up an aircraft company in America and invited Frank to join him in the venture.

On 1st April 1918 The Royal Air Force came into being. It was not welcomed by the RFC and particularly by the RNAS who lost their Naval uniforms and ranks. New government departments were formed and Frank found that he was now working for the Air Ministry Technical Department in a testing and consulting role. He was based at Norwich where Boulton and Paul were producing several aircraft types from fighters to flying boats though he worked with other contractors too.

The war came to an end in November and two months later, Frank left the RAF.

The aviation industry which Frank had joined as an apprentice less than five years before when it was little better than a cottage industry had undergone an explosive growth. Its products had changed from clever machines built only for the enjoyment of users and spectators to become practical instruments, not only as weapons of war but also as carriers of people and goods at speeds and over distances that other means of transport couldn’t rival. With the range of contacts he had in the aviation industry and the wide recognition of his capabilities and experience as a test pilot of all types of aeroplanes he looked forward to the future with confidence. Already a qualified engineer before he joined the service, he had flown and tested a wide range of aeroplanes - and seaplanes - and had built a reputation for his conscientious approach to testing and his comprehensive and meticulous reports.

Almost before he had put on a civilian suit he was offered a job by Geoffrey De Havilland, Chief Designer of the Aircraft Manufacturing Company. Their DH11 twin engine bomber had not been cancelled and the prototype was ready for testing.

Someone in the upper echelons had realised that pilot training in the RFC was a shambles. Any pilot who was available between postings, medically unfit for combat, even newly qualified pilots could be sent to instruct pupils in whatever way they chose. Once a pupil could take off, turn and land he could be considered qualified. Most ‘instructors’ hated the job and referred to their pupils as ‘Huns’, because they killed more instructors than the enemy.

The campaigning of Major Smith-Barry finally had some effect and he was allowed to set up a School at Gosport specifically to train instructors. Frank posted himself there for a course.

The school flew in all kinds of weather, practised cross-wind, even downwind take offs and landings, taught aerobatics and emergency procedures and used several types of aeroplanes with different flying characteristics. Back with 18th Wing where Gosport-style training was being introduced Frank and two colleagues set up their own Special Instructors’ Flight at London Colney to train more instructors. At the same time, he was running his own ‘Fighting’ courses for pilots due for posting to France.

His workload increased when the Americans arrived. A squadron with a mix of newly trained and experienced pilots were based alongside Frank’s unit and shared the same messing facilities. The Americans needed aeroplanes and initially used any outdated types the RFC and RNAS didn’t need. They also had to learn RFC English for many aviation components and activities. Although it was not part of his job Frank became heavily involved. He built up a good relationship with Col. William Larned of the US Technical HQ who was trying to source aircraft and equipment from the British, French and Italians.

Other Allies arrived for training. Early in 1917 there had been a revolution in Russia. (It was in March on our Gregorian calendar. Russia still used the Julian calendar, so it was in February for them). It started with a strike by women, the army and navy joined them and the Czar abdicated. The new government decided to continue the war and sent a group of airmen to England for training. That was Frank’s job. The Russians had only odd scattered words of English. Luckily, a few spoke some French, in which Frank was fluent. They increased Frank’s workload – and the crash rate – and went home in time for the Bolshevik take-over of the government in October (November in Russia).

Meanwhile, Frank’s job enlarged. The nature of fighting was changing as new types were introduced and he was doing more experimental flying with new aeroplanes and new engines. A significant engine was the Liberty, designed in the US (to a great extent a development of the Mercedes III) and put into large scale production. His connections with the Americans was now official. He had meetings with many senior and influential people including Colonel Billy Mitchell who was to command all USAAC units in France. (Post-war he campaigned so vigorously to spend money or bombers rather than battleships that he was court-martialled). Col. Bill Larned had realised that, without the urgency of war, America had not yet developed the industrial, technical and political background needed now by the fighting forces and would be post war, by expanding commercial aviation. He had plans to set up an aircraft company in America and invited Frank to join him in the venture.

On 1st April 1918 The Royal Air Force came into being. It was not welcomed by the RFC and particularly by the RNAS who lost their Naval uniforms and ranks. New government departments were formed and Frank found that he was now working for the Air Ministry Technical Department in a testing and consulting role. He was based at Norwich where Boulton and Paul were producing several aircraft types from fighters to flying boats though he worked with other contractors too.

The war came to an end in November and two months later, Frank left the RAF.

The aviation industry which Frank had joined as an apprentice less than five years before when it was little better than a cottage industry had undergone an explosive growth. Its products had changed from clever machines built only for the enjoyment of users and spectators to become practical instruments, not only as weapons of war but also as carriers of people and goods at speeds and over distances that other means of transport couldn’t rival. With the range of contacts he had in the aviation industry and the wide recognition of his capabilities and experience as a test pilot of all types of aeroplanes he looked forward to the future with confidence. Already a qualified engineer before he joined the service, he had flown and tested a wide range of aeroplanes - and seaplanes - and had built a reputation for his conscientious approach to testing and his comprehensive and meticulous reports.

Almost before he had put on a civilian suit he was offered a job by Geoffrey De Havilland, Chief Designer of the Aircraft Manufacturing Company. Their DH11 twin engine bomber had not been cancelled and the prototype was ready for testing.

It was powered by A.B.C. Dragonfly engines which the Air Ministry had ordered in large quantities but had only just gone into service. Frank thought the Dragonfly to be a very bad design. He called it a ‘metallic assembly of infirmities’. He was more dismayed to learn that Major General Sefton Brancker intended to accompany him on the first flight. Brancker was a director of the company and Frank couldn’t dissuade or refuse to take him. (Brancker’s insistence on being involved ultimately led to his death in the crash of the R101).

They taxied out (to the very spot on Hendon aerodrome where Frank had taken off on his first solo in a Boxkite years before). The Dragonflies roared into life. As the DH 11 cleared the far boundary of the field at about 200 ft the starboard engine clattered into silence. Ahead was a hill, a church and a sea of houses. The port engine was still running and the aeroplane still flying so Frank used the yet untested controls to complete a 180° turn. At this point the port engine lost power and spluttered to an intermittent tick-over. With just enough height and speed to hop over the telegraph wires Frank was able to carry out a Gosport style downwind landing. Brancker was impressed.

De Havilland had an associated company, Aircraft Transport and Travel. With it he started the first commercial scheduled airline, flying between London and Paris using DH 16s – modified DH 9s with a 4-seat passenger cabin. Frank became involved in sorting out technical and operational problems and frequently acting as reserve pilot. It was on one of these occasions when he carried out a memorable test.

De Havilland had an associated company, Aircraft Transport and Travel. With it he started the first commercial scheduled airline, flying between London and Paris using DH 16s – modified DH 9s with a 4-seat passenger cabin. Frank became involved in sorting out technical and operational problems and frequently acting as reserve pilot. It was on one of these occasions when he carried out a memorable test.

AT&T asked to borrow a DH16 for a flight to Paris and the one which Frank took had been prepared for a special test. He had already done a range of tests with flaps during his time at Farnborough. De Havilland wanted to find out whether spoilers would be more effective. A DH16 was modified by having a long trough cut into the upper surface of the wing just behind the spar. It stretched from wing tip to wing tip.

This was filled by a narrow slat of wood, the spoiler, which lay flush with the upper surface. A hand wheel in the cockpit would raise the slat so that it impacted on the airflow over the wing. That should increase the drag and produce a rapid rate of descent.

This was filled by a narrow slat of wood, the spoiler, which lay flush with the upper surface. A hand wheel in the cockpit would raise the slat so that it impacted on the airflow over the wing. That should increase the drag and produce a rapid rate of descent.

On his way to Croydon with time to spare Frank thought he could fit in a tentative test. Prudently, he climbed another 2000 ft higher. He turned the wheel – and nothing happened. Turning more had no effect. Had the control become disconnected? More vigorous turning. Suddenly, the nose dropped. The whole plane shuddered, rolled and fell about in every direction. Frank closed the throttle and hung onto the vibrating stick with both hands. In the all-enveloping turbulent airflow the tail controls had no effect. Frank rolled the shaking wheel to close the spoilers. He had to go some way past the point where it had all it started. Just as suddenly the shaking stopped and peace returned. His altimeter told him he was just under 2000 ft.

De Havilland abandoned the spoiler tests and it was 43 years before Frank used spoilers again. This time they were properly sized power operated spoilers on a jet transport.

In 1920, the Aircraft Manufacturing Company closed down and De Havilland set up his own business. Now a free lance test pilot Frank was hired to fly a wide variety of aeroplanes, many with curious features. Free of the need to build aircraft to meet military specifications some designers seized the opportunity to incorporate their radical ideas and make the ‘next best thing’ in aviation.

There was the twin-engined long-range mailplane. Two Napier Lion engines were fitted side by side in an ‘engine room’ behind the pilots’ cockpit. They drove twin propellers on the wings by gears and shafts and could be serviced in flight by a long-suffering engineer who stood between them. The new metal construction was meant to cope would with the unusual distribution of weight. Frank found that the tail controls needed adjustment after every flight, they were constantly slackening. It was simply because the fuselage was bending on every landing. That, and the fact that they could never get the engines to synchronise properly put paid to the design.

A better design was the Boulton Paul P.8. A development of the Bourges bomber, the P.8 was to be a airliner carrying 7 passengers. When the designer realised that, with minor modifications, it could be a competitor for the Daily Mail’s £10,000 prize for flying the Atlantic the first prototype was built as the P.8 Atlantic. The passenger cabin held 800 gallons of fuel, giving a range of 3,850 miles. In an emergency a dump valve could drop all the fuel in 25 seconds and the empty tanks would keep the aeroplane afloat.

The pilot’s cabin was completely enclosed, an unusual feature in 1919. The handling was expected to be as good as the Bourges which could be trimmed to fly hands off with only occasional nudges of the rudder. So the designer added a special lever which locked the elevator and ailerons and transferred control of the rudder to the control wheel. Two extra fins had been fitted to the tailplane to help with asymmetric flight. The two Napier Lion 450 hp engines were powerful enough that if one failed, the other would maintain altitude, once two hours of fuel had been burned, or dumped.

Everything was ready for the first flight. Frank was about to do the final engine runs when the Managing Director appeared with a VIP. It was very important, said the MD, that the VIP should see the first flight. Better still, he could come on the flight because he had a train to catch. Are you ready to go? Frank had to give in. He would keep the flight short. He ran up the port engine, then the starboard engine. All was well. The test observer and the VIP climbed aboard and Frank taxied out for take off.

They had just left the ground when suddenly the port engine stopped. The swing to the left caused the wing tip to hit the ground and the lovely new aeroplane and all the hopes of winning the prize cartwheeled into a heap of wreckage. Frank had a few bruises, the observer lost a few teeth and the VIP was probably in time to catch his train. (Had the engine tests ben completed before the flight they would have revealed that the fuel system did not provide sufficient fuel flow when both engines were running at full power}.

De Havilland abandoned the spoiler tests and it was 43 years before Frank used spoilers again. This time they were properly sized power operated spoilers on a jet transport.

In 1920, the Aircraft Manufacturing Company closed down and De Havilland set up his own business. Now a free lance test pilot Frank was hired to fly a wide variety of aeroplanes, many with curious features. Free of the need to build aircraft to meet military specifications some designers seized the opportunity to incorporate their radical ideas and make the ‘next best thing’ in aviation.

There was the twin-engined long-range mailplane. Two Napier Lion engines were fitted side by side in an ‘engine room’ behind the pilots’ cockpit. They drove twin propellers on the wings by gears and shafts and could be serviced in flight by a long-suffering engineer who stood between them. The new metal construction was meant to cope would with the unusual distribution of weight. Frank found that the tail controls needed adjustment after every flight, they were constantly slackening. It was simply because the fuselage was bending on every landing. That, and the fact that they could never get the engines to synchronise properly put paid to the design.

A better design was the Boulton Paul P.8. A development of the Bourges bomber, the P.8 was to be a airliner carrying 7 passengers. When the designer realised that, with minor modifications, it could be a competitor for the Daily Mail’s £10,000 prize for flying the Atlantic the first prototype was built as the P.8 Atlantic. The passenger cabin held 800 gallons of fuel, giving a range of 3,850 miles. In an emergency a dump valve could drop all the fuel in 25 seconds and the empty tanks would keep the aeroplane afloat.

The pilot’s cabin was completely enclosed, an unusual feature in 1919. The handling was expected to be as good as the Bourges which could be trimmed to fly hands off with only occasional nudges of the rudder. So the designer added a special lever which locked the elevator and ailerons and transferred control of the rudder to the control wheel. Two extra fins had been fitted to the tailplane to help with asymmetric flight. The two Napier Lion 450 hp engines were powerful enough that if one failed, the other would maintain altitude, once two hours of fuel had been burned, or dumped.

Everything was ready for the first flight. Frank was about to do the final engine runs when the Managing Director appeared with a VIP. It was very important, said the MD, that the VIP should see the first flight. Better still, he could come on the flight because he had a train to catch. Are you ready to go? Frank had to give in. He would keep the flight short. He ran up the port engine, then the starboard engine. All was well. The test observer and the VIP climbed aboard and Frank taxied out for take off.

They had just left the ground when suddenly the port engine stopped. The swing to the left caused the wing tip to hit the ground and the lovely new aeroplane and all the hopes of winning the prize cartwheeled into a heap of wreckage. Frank had a few bruises, the observer lost a few teeth and the VIP was probably in time to catch his train. (Had the engine tests ben completed before the flight they would have revealed that the fuel system did not provide sufficient fuel flow when both engines were running at full power}.

Boulton Paul P. 8 Atlantic – before and after.

Frank learned to avoid any first flight that was to be done at a specific time, regardless of the weather, or before an audience or a VIP visitor. In Holland the Mayor was coming to visit and Koolhoven’s new fighter was hastily prepared for flight. No one noticed that the rudder control locking nuts were not fitted. The pins dropped out in flight and Frank’s landing was ‘not his best’.

He was asked to fly a new Westland design. He thought the little airfield at Yeovil was too small and persuaded the company to transport the aeroplane to Andover, a much larger field. The tests went off successfully. However, when Westland’s next design to be tested, the accountants refused to hire Frank – he ‘was too expensive’. They resorted to the other breed of test pilots, the ‘fly anything boys’.