Sir Francis Chichester 1901-1972 (Oct 2013)

The arrival in Darwin

The arrival in Darwin

He had a tough childhood in Devon and, aged just 17, escaped to New Zealand, determined to ‘make his fortune’. After a number of jobs, miner, lumberjack, salesman he finally he grew a very successful business in real estate and forestry. As a side venture, he and a business partner set up a company offering pleasure flights to tourists. This triggered an interest in flying and when Chichester returned to England in 1929 he joined Brooklands flying club to gain his pilot’s licence. He bought a Gypsy Moth, which he named Madame Elijah, and developed his skills in flights around England and Europe.

Then, despite his relative inexperience, he announced his intention to fly to Australia. Only the famous Bert Hinckler had done this the previous year. Chichester left Croydon in December 1929 hoping to beat Hinckler’s record but a delay waiting for a replacement propeller to be sent to Libya ruined that plan. He arrived successfully in Sydney after 180 flying hours. The Tasman Sea lay ahead as an impossible task for a Moth so it finished its journey to New Zealand by ship.

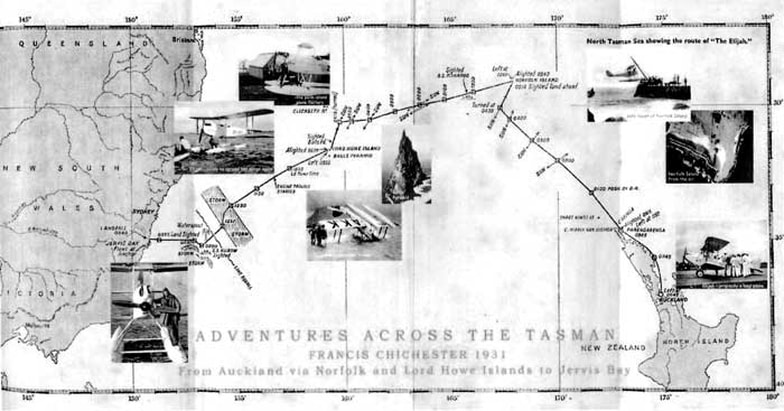

The challenge of the Tasman remained and Chichester realised that he could reach Australia if he fitted the Moth with floats to alight on the sea and refuel at Norfolk Island and Lord Howe Island. The real problem now was to find these tiny spots in the sea. The only method of position-fixing available was to take sun-shots with a sextant - not easy in the cramped vibrating cockpit - then laboriously work out the fix with pencil and paper. He decided to use the principle of ‘off-course navigation’ i.e. deliberately aiming for a point to one side of the island. When this point was reached there would be no doubt which way to make a 90º turn for the final leg to the island. To reduce potential errors in calculation, Chichester worked out a series of examples based on his estimate of the sun’s position at the time of his expected arrival at critical points on his course.

However well prepared he was, the flight was not easy. At one point his course was blocked by the low cloud of a rainstorm, needing a diversion. ‘Round the storm we flew into calm air under a weak lazy sun. I took out the sextant and got two shoots. It took me thirty minutes to work them out, for the engine kept back firing, and my attention wandered every time it did... ‘. But the navigation system worked successfully and the Moth became the first aircraft to visit both Norfolk Island and Lord Howe. There was no harbour at Lord Howe so the Moth was anchored for the night close to the beach. Overnight, the wind changed.

Next morning, Chichester looked out to see his Moth overturned in the water. He thought it was all over and was resigned to giving up. The damage to the upper wing seemed irreparable and the tiny island (pop. 150) offered few facilities. But the eager islanders thought otherwise. They dismantled the Moth, hauled it ashore and stripped the engine. A list of spares was sent to de Havilland and in 10 weeks, the repaired Moth was re-launched.

Next morning, Chichester looked out to see his Moth overturned in the water. He thought it was all over and was resigned to giving up. The damage to the upper wing seemed irreparable and the tiny island (pop. 150) offered few facilities. But the eager islanders thought otherwise. They dismantled the Moth, hauled it ashore and stripped the engine. A list of spares was sent to de Havilland and in 10 weeks, the repaired Moth was re-launched.

Chichester flew on, experiencing storms, dodging waterspouts, and nursing a troubled engine to complete the first aerial crossing of the Tasman Sea.

Now he was in Australia. He’d connected with his flight from England so why not carry on and fly round the world.

A route was planned north through the Philippines and China. In Japan he reached Katsuura. On taking off from the harbour the background of hills disguised a line of overhead telephone wires and the Moth flew directly into them. They catapulted the seaplane back down onto the harbour wall. Chichester’s injuries included 13 broken bones and he was not fully recovered for 5 years.

A route was planned north through the Philippines and China. In Japan he reached Katsuura. On taking off from the harbour the background of hills disguised a line of overhead telephone wires and the Moth flew directly into them. They catapulted the seaplane back down onto the harbour wall. Chichester’s injuries included 13 broken bones and he was not fully recovered for 5 years.

By then it was 1936 and the wanderlust returned. So he bought a Puss Moth and flew it through Asia and Europe to England.

When WWII broke out he was 38 but he applied – three times – to join the RAF. Each time he was rejected for nearsightedness and astigmatism. Grounded, he became Chief Navigation Instructor at the RAF’s Central Flying School and wrote many of the manuals for pilot-navigators. After the war, he started a map-selling business (which survived until 2012) and took up sailing.

When WWII broke out he was 38 but he applied – three times – to join the RAF. Each time he was rejected for nearsightedness and astigmatism. Grounded, he became Chief Navigation Instructor at the RAF’s Central Flying School and wrote many of the manuals for pilot-navigators. After the war, he started a map-selling business (which survived until 2012) and took up sailing.

In 1960 a half crown bet (that's two shillings and sixpence or 12½p) encouraged him to join a single-handed race across the Atlantic. He won, by a margin of an astonishing 16 days. Further Atlantic crossings raised his sights to a round-the-world voyage. This brought him, at 65 years of age, his greatest moment of fame – and a knighthood.

Sir Francis Chichester might be remembered best for his sailing achievements but it seems that he could have viewed it differently. It’s significant that all of his yachts were named Gypsy Moth.

Sir Francis Chichester might be remembered best for his sailing achievements but it seems that he could have viewed it differently. It’s significant that all of his yachts were named Gypsy Moth.