Trans-Atlantic Tow (Mar 2020)

It’s not entirely clear where the idea originated but it lay smouldering in the Montreal office of the man in charge of the RAF Ferry Command, Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill. He was building up the operation which delivered American aeroplanes to the RAF simply by flying them across the Atlantic rather than being packed into ships and taking the risky journey through U-boat infested waters. If there were gliders to be delivered as well, why not hang them behind Dakotas and deliver two aeroplanes for the fuel of one. And, why not add even more value by loading the glider with cargo!

Bowhill decided to give it a try and – here’s the other interesting unknown – the man he chose to fly the glider was none other than his son-in-law. Was he just trying to keep the achievement of a successful ‘first’ within the family or was there another, more sinister reason? And what did his daughter have to say about it?

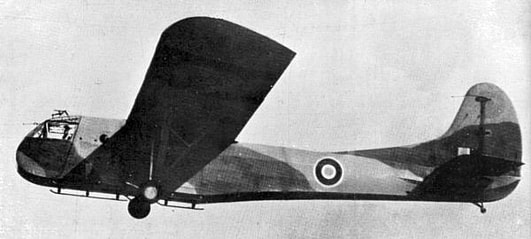

Wg Cdr Richard Seyes was not impressed. After a tour as a night fighter pilot he was enjoying the challenge of flying transports along the difficult and weather-wracked route to Europe. He had never flown, or even thought of flying, a glider. But - orders were orders. He flew to the UK for a quick course in the Hotspur glider, then larger cargo gliders. Next it was back to the States to be introduced to the Waco CG-4, which the RAF called the Hadrian.

Bowhill decided to give it a try and – here’s the other interesting unknown – the man he chose to fly the glider was none other than his son-in-law. Was he just trying to keep the achievement of a successful ‘first’ within the family or was there another, more sinister reason? And what did his daughter have to say about it?

Wg Cdr Richard Seyes was not impressed. After a tour as a night fighter pilot he was enjoying the challenge of flying transports along the difficult and weather-wracked route to Europe. He had never flown, or even thought of flying, a glider. But - orders were orders. He flew to the UK for a quick course in the Hotspur glider, then larger cargo gliders. Next it was back to the States to be introduced to the Waco CG-4, which the RAF called the Hadrian.

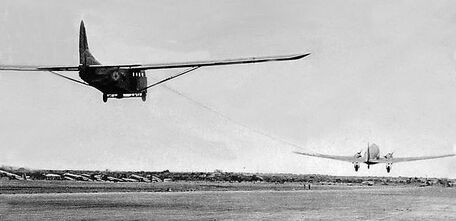

The tow rope being attached.

(NB The glider is not ‘Voo’Doo’).

The tow rope being attached.

(NB The glider is not ‘Voo’Doo’).

The American tow rope fittings had to be replaced by the RAF’s ‘A’ type Lobel fittings, like a clenched hand which held the steel ball on the end of the rope. The rope itself, 350 ft long, was 3.5 ins circumference and a wire for the radio link between tug and glider ran through it.

Between the three nylon strands pieces of tape were threaded, 10 in all. After every tow, the rope was inspected and one strand pulled off. The rope had its own servicing log book.

Between the three nylon strands pieces of tape were threaded, 10 in all. After every tow, the rope was inspected and one strand pulled off. The rope had its own servicing log book.

A Dakota was assigned to them flown by Flt Lts Bill Longhurst (Canada) and Charles Thomson (New Zealand). The Dakota crew members were flight engineer Plt. Off. R. H. Wormington (UK) and radio operator Gordon Wightman, a Canadian civilian. The Dakota was fitted with extra fuel tanks, more than doubling its normal fuel capacity to 1900 gallons.

In April 1943 training began. A number of flights of increasing distances carrying increasing weights of cargo were made. They visited several places in eastern Canada and the north east of America, even including an over-water flight to Bermuda. The return flight to Virginia set a world record for a non-stop towed flight of 1187 miles. That was no speed record. It took them all of 8 hours and 50 minutes.

During this ‘training’ they quickly realised that whoever came up with the plan had never flown a glider being towed. It sounds so simple. ‘Just follow that aeroplane and he’ll drag you along through the sky’.

In April 1943 training began. A number of flights of increasing distances carrying increasing weights of cargo were made. They visited several places in eastern Canada and the north east of America, even including an over-water flight to Bermuda. The return flight to Virginia set a world record for a non-stop towed flight of 1187 miles. That was no speed record. It took them all of 8 hours and 50 minutes.

During this ‘training’ they quickly realised that whoever came up with the plan had never flown a glider being towed. It sounds so simple. ‘Just follow that aeroplane and he’ll drag you along through the sky’.

In following the tug there are complications. The glider normally flies just above the turbulent wake of the tug and the pilot has an instrument which measures the tow rope’s ‘angle of dangle’. This helps to maintain position relative to the tug and is particularly useful, even essential, in poor visibility or in cloud. However, the air is seldom smooth and the tow rope must be flexible enough to absorb shocks. That makes it act like a piece of elastic. If the tug flies into a gust its speed changes and the tow rope goes slack. The gliders slows, the rope tightens, stretches and the glider accelerates so that the rope goes slack again.

If the stretch and slacken cycle is allowed to continue it quickly gets worse and could end in breaking the rope. Being out of position to one side has a similar effect in that the glider swings back, usually too far to the other side.

If the stretch and slacken cycle is allowed to continue it quickly gets worse and could end in breaking the rope. Being out of position to one side has a similar effect in that the glider swings back, usually too far to the other side.

There is no autopilot that could cope with this rash of divergent phugoids. Being towed demands hand flying and constant attention from the pilot. Because of this Seyes and Gobeil’s 8 hr 50 min record was a hard won achievement. They had more than towrope troubles.

During this long testing flight, they were carrying a passenger and cargo - some coral rocks tied down by ropes. Although they were in a clear blue sky they ran into severe turbulence. So severe that the passenger was catapulted into the steel tube fuselage structure and briefly knocked out. Some of the rocks broke free and punctured the fabric covering. No serious damage seemed to have been done so the rocks were tied down. The Dakota climbed to get into smoother air only to run into more turbulence. Once again the cargo broke its ropes and punctured more holes. After landing they found no real damage to the structure but they thought that if they had been carrying a full load the wings would have been in danger of coming off.

During this long testing flight, they were carrying a passenger and cargo - some coral rocks tied down by ropes. Although they were in a clear blue sky they ran into severe turbulence. So severe that the passenger was catapulted into the steel tube fuselage structure and briefly knocked out. Some of the rocks broke free and punctured the fabric covering. No serious damage seemed to have been done so the rocks were tied down. The Dakota climbed to get into smoother air only to run into more turbulence. Once again the cargo broke its ropes and punctured more holes. After landing they found no real damage to the structure but they thought that if they had been carrying a full load the wings would have been in danger of coming off.

It might be because they’d had enough of training that they declared themselves ready to cross the Atlantic. They would follow the usual North Atlantic route used by Ferry Command for all but its long-range aircraft.

It was on 23 June, 1943 at Montreal that the Hadrian was loaded with its cargo, 3360 lbs of it. There was blood plasma and vaccine to go on to Russia, aircraft, engine and radio parts. Into a corner Richard Seyes tucked a bunch of bananas. When he got home, his family would be the only people in Britain to enjoy a wartime banana. Onlookers who knew what was afoot discussed how likely it was that the Hadrian would reach Prestwick safely. The average odds were 1 in 7, the best 1 in 5.

It was on 23 June, 1943 at Montreal that the Hadrian was loaded with its cargo, 3360 lbs of it. There was blood plasma and vaccine to go on to Russia, aircraft, engine and radio parts. Into a corner Richard Seyes tucked a bunch of bananas. When he got home, his family would be the only people in Britain to enjoy a wartime banana. Onlookers who knew what was afoot discussed how likely it was that the Hadrian would reach Prestwick safely. The average odds were 1 in 7, the best 1 in 5.

The crews climbed aboard. The weather was perfect and after a rather long run, the heavily loaded train lifted off the runway. Flying in parallel was a Catalina as an insurance against a mid-ocean rope break though it would be of no help on the first 700 mile overland leg. The first four hours went smoothly, then they ran into a line of clouds. Unable to climb over them the Dakota picked its way through the turbulent gaps below the cloud.

The pilots found it difficult to hold their height, swinging a hundred feet or more above, below and from side to side. The tow rope hung limp or twanged tight, the glider’s speed varying from 95 to 165 mph. It began to snow and sometimes they lost sight of the Dakota. Ominous noises came from behind them as the cargo shifted. Ice formed on the glider’s wings.

They discussed the situation with the Dakota’s crew. The least worst thing to do was to press on to the nearest airfield – Goose Bay. After three long hours of fighting through the weather front Goose Bay came into view. Seyes released the tow rope and enjoyed a few minutes of calm free flight before landing. The Dakota followed. Every crew member was exhausted.

They discussed the situation with the Dakota’s crew. The least worst thing to do was to press on to the nearest airfield – Goose Bay. After three long hours of fighting through the weather front Goose Bay came into view. Seyes released the tow rope and enjoyed a few minutes of calm free flight before landing. The Dakota followed. Every crew member was exhausted.

The weather held them on the ground for four days, an enforced rest which they needed. They left Canada on 27th June and climbed to a clear patch between cloud layers. There was nothing to be seen for five hours until the mountains of Greenland appeared ahead. Then suddenly, they were overtaken by three flights of B-26 Marauders who passed them as if they were standing still.

They looked for the airfield at Narsarsuaq, known as Bluie West 1. It had been built on a strip of land at the head of a fiord. (It was one of three parallel fiords and notoriously difficult to find if cloud covered the mountains.

Pilots knew they had chosen the correct fiord entrance only when they passed a wrecked ship. If they had chosen the wrong fiord it was too narrow to turn round. The only escape was to climb into mountain-stuffed clouds and try again). Happily, Seyes and Gobeil had no such problem and landed comfortably, becoming the first glider to land in Greenland.

They looked for the airfield at Narsarsuaq, known as Bluie West 1. It had been built on a strip of land at the head of a fiord. (It was one of three parallel fiords and notoriously difficult to find if cloud covered the mountains.

Pilots knew they had chosen the correct fiord entrance only when they passed a wrecked ship. If they had chosen the wrong fiord it was too narrow to turn round. The only escape was to climb into mountain-stuffed clouds and try again). Happily, Seyes and Gobeil had no such problem and landed comfortably, becoming the first glider to land in Greenland.

The rope was checked and they found one of the three strands was nearly worn through. They were grounded for two days by the weather, giving them ample time to resplice the end of the tow rope and to fit in a little fishing.

On the 30th, they were ready to go. It would have been helpful if the wind had been straight down the runway. The Dakota, which was more heavily loaded than the Hadrian lifted off the ground (the witnesses said) about two feet from the runway’s end. It was impossible to climb out of the fiord so they flew along it to the sea then followed the coast around Cape Farewell. Finally they could set course for Iceland over the open Atlantic.

The weather was foul - squalls of intermittent low cloud and fog – and heavy turbulence. The Dakota often disappeared from view and both aircraft began to accumulate ice. Condensation inside the glider fell as snow. It took an hour of rattling through the severe turbulence before the low cloud broke up and they could climb clear. When the mountains of Iceland appeared ahead they were delighted by the progress they had made only to be disappointed when the mountains turned out to be the tops of distant cu-nim clouds. This happened again. Finally, they were met by no mirage. Three American fighters appeared to escort them into Reykjavik. They had been sent because the Germans regularly patrolled the mid-Atlantic to collect meteorological data. A Condor could have easily shot down the lumbering tug/glider combination.

Voo-Doo landed and the Dak came in to drop the tow rope. Normally they aimed for a grassy area near the airport but at Reykjavik there were too many houses crowding the field. The rope was dropped onto the runway. The metal fittings at both ends were damaged. Someone was found to work overnight to make the rope serviceable again.

Next day, 1st July, take off was into a sky of scudding low clouds. The Dak weaved its way through the clouds and their turbulence to find clearer and smoother air. (The promised fighter escort from the USAAC failed to show up – as did the RAF escort which should have met them as they neared Scotland). But for the next two hours they enjoyed bright sunshine. They were on their last leg – spirits rose.

It didn’t last long. The clouds and their turbulence returned and their first landfall, a tiny Hebridean island, was just visible through the murk. Their destination, Prestwick was the other side of Glasgow - and no-one had briefed them about its barrage balloons.

On the 30th, they were ready to go. It would have been helpful if the wind had been straight down the runway. The Dakota, which was more heavily loaded than the Hadrian lifted off the ground (the witnesses said) about two feet from the runway’s end. It was impossible to climb out of the fiord so they flew along it to the sea then followed the coast around Cape Farewell. Finally they could set course for Iceland over the open Atlantic.

The weather was foul - squalls of intermittent low cloud and fog – and heavy turbulence. The Dakota often disappeared from view and both aircraft began to accumulate ice. Condensation inside the glider fell as snow. It took an hour of rattling through the severe turbulence before the low cloud broke up and they could climb clear. When the mountains of Iceland appeared ahead they were delighted by the progress they had made only to be disappointed when the mountains turned out to be the tops of distant cu-nim clouds. This happened again. Finally, they were met by no mirage. Three American fighters appeared to escort them into Reykjavik. They had been sent because the Germans regularly patrolled the mid-Atlantic to collect meteorological data. A Condor could have easily shot down the lumbering tug/glider combination.

Voo-Doo landed and the Dak came in to drop the tow rope. Normally they aimed for a grassy area near the airport but at Reykjavik there were too many houses crowding the field. The rope was dropped onto the runway. The metal fittings at both ends were damaged. Someone was found to work overnight to make the rope serviceable again.

Next day, 1st July, take off was into a sky of scudding low clouds. The Dak weaved its way through the clouds and their turbulence to find clearer and smoother air. (The promised fighter escort from the USAAC failed to show up – as did the RAF escort which should have met them as they neared Scotland). But for the next two hours they enjoyed bright sunshine. They were on their last leg – spirits rose.

It didn’t last long. The clouds and their turbulence returned and their first landfall, a tiny Hebridean island, was just visible through the murk. Their destination, Prestwick was the other side of Glasgow - and no-one had briefed them about its barrage balloons.

The windscreen of the Dakota was suddenly filled with the view of a menacing balloon. The Dakota pilot executed a neat climbing steep turn. Somehow, the Hadrian followed although the tale later told of the tug flying over the glider in the opposite direction is almost certainly an exaggeration. After that, finding Prestwick was an anti-climax.

They circled the airfield waiting for the scheduled aircraft carrying a newsreel cameraman to arrive. It failed to turn up so the Hadrian released and landed.

They circled the airfield waiting for the scheduled aircraft carrying a newsreel cameraman to arrive. It failed to turn up so the Hadrian released and landed.

Seyes and Gobeil shook hands, having achieved the unnecessarily achievable. They still weren’t finished with tugs. They hitched a lift on the one which came out to pull the glider off the airfield. In the picture Gobeil is on the left and Seyes is wearing his lucky red skullcap. (Clearly, it worked!)

The nose was lifted and the cargo extracted to be sent on its way by more conventional transport.

Voo-Doo had followed the Dakota for over 3500 miles in a flight time of 28 hours and 3 minutes (spread over eight days). Their average speed was 125 mph.

It was officially decided that regular trans-Atlantic glider flights were ‘not feasible’. Someone suggested that Voo-Doo should be donated to a museum but, in getting it there, it crashed and was written off. The Dakota went on to ‘other things’.

Oh, and the bananas, having been frost-bitten and de-frosted several times had to be ‘disposed of’.

Voo-Doo had followed the Dakota for over 3500 miles in a flight time of 28 hours and 3 minutes (spread over eight days). Their average speed was 125 mph.

It was officially decided that regular trans-Atlantic glider flights were ‘not feasible’. Someone suggested that Voo-Doo should be donated to a museum but, in getting it there, it crashed and was written off. The Dakota went on to ‘other things’.

Oh, and the bananas, having been frost-bitten and de-frosted several times had to be ‘disposed of’.