Balloon Bail-Out– the Perils of Parachuting (Sept 2013)

It took man multiple lifetimes of wishing and experimenting to get himself up in the air but, no sooner had a practical balloon been invented he wanted to abandon it. In fact, the means of doing so – by parachute – had been designed long before the first Montgolfiere balloon lifted off in 1783. Even Leonardo’s design of 1485 is preceded by an unattributed sketch of 1470 showing a parachute harness. Fausto Veranzio is believed to have been the first base-jumper when he tested his parachute by leaping off the Campanile in Venice in 1617. In 1783, Louis-Sébastien Lenormand tested his device by jumping off the tower of Montpellier Observatory. He coined the word para (defence against) -chute (a fall).

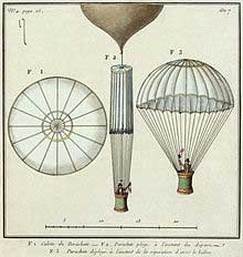

The Montgolfiere hot air and Charles hydrogen balloons represented a golden opportunity for real parachuting. The first proper descent from a balloon was in 1785 in a parachute designed by Jean Pierre Blanchard. The parachutist was, in the best traditions of aviation experiments, a dog. But the man who made parachuting a popular spectacle was André Garnerin. His 23 ft diameter canvas umbrella carried a basket in which Garnerin stood. On 22 October 1797, he dropped from a hydrogen balloon at 3000 ft over Paris.

The Montgolfiere hot air and Charles hydrogen balloons represented a golden opportunity for real parachuting. The first proper descent from a balloon was in 1785 in a parachute designed by Jean Pierre Blanchard. The parachutist was, in the best traditions of aviation experiments, a dog. But the man who made parachuting a popular spectacle was André Garnerin. His 23 ft diameter canvas umbrella carried a basket in which Garnerin stood. On 22 October 1797, he dropped from a hydrogen balloon at 3000 ft over Paris.

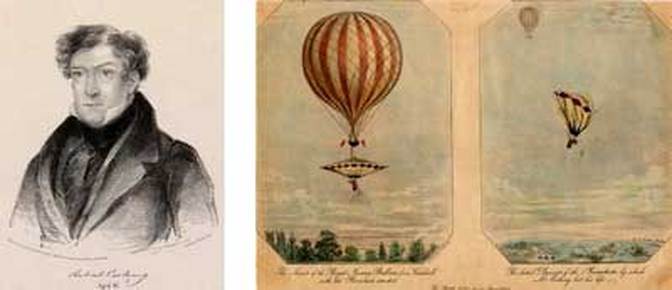

Garnerin’s exploits were discussed by Sir George Cayley in his paper, On Aerial Navigation, published in 1810. He thought that the oscillations would be cured by making the parachute cone-shaped so that the trapped air would spill evenly. This idea was seized on by Robert Cocking who had witnessed Garnerin’s performance in 1802. He spent years developing his solution. His parachute was constructed to be adequately strong yet as light as possible. The 34 ft diameter outer ring (of three concentric rings) was made of tin tube with intermediate spars of wood. The covering was of ‘the finest Irish linen’ with a wicker basket suspended beneath. The parachute was even intended to be steered by a system of ropes and pulley blocks. Despite Cocking’s best efforts, the weight was at least 220 lbs, with Cocking himself tipping the scales at 170 lbs. At the age of 61 and with no parachuting experience it took him some time to persuade the noted aeronaut Charles Green to take the parachute aloft. Even then, Green refused to operate the release mechanism so a ‘liberating iron’ was devised with a release rope dangling down to the parachutist’s basket.

On 24 July 1837, thousands of spectators attended the Grand Fete Day at Vauxhall Gardens. The main attraction was Cocking’s ascent and at 7.35 pm the balloon lifted off accompanied by the national anthem played by band of the Surrey Yeomanry. The aim was to reach 8000 ft but the weight made the ascent very slow and at 5000 ft Cocking decided that it was high enough. ‘Well now, I think I shall leave you’ called Cocking. He wished the balloonists ‘good night’ and pulled the rope of the release mechanism.

At first, nothing happened so he pulled harder. The parachute fell away but, after a brief three or four seconds, the canopy was seen to collapse and the wreckage fell spinning to the ground.

The inquest into Cocking’s death had to cope with several conflicting statements. However, a broken piece of cord on Cocking’s left wrist which had made a deep incision suggests that the release mechanism could have been the primary cause. After the first pull which failed to release the parachute it seems that, to get a firmer grip, Cocking had wrapped the rope round his wrist. Thus when the parachute broke free, Cocking remained attached to the balloon and was dragged up into the structure, damaging the parachute before the rope finally broke.

Tests carried out some years later did indeed show that a properly constructed parachute to Cocking’s design (and using Sir George Cayley’s principles) would have worked well. But no one ever felt the need to prove it with a live jump.

A vent in the top of the canopy was soon adopted which achieved a stable descent and drops from balloons became a popular show attraction. Piloted balloons suffered severe loss of control when the weight of the parachute and its occupant was suddenly released so parachutists began to use smaller, unpiloted balloons. They needed no ballast for control and could safely be abandoned by the parachutist at the chosen height. Some were gas-filled, others so-called ‘smoke’ balloons inflated by hot air. To encourage rapid deflation a sandbag was attached to the top of the smoke balloon. At the point of release, this rolled the balloon inverted allowing a rapid escape of hot air from the now upward-facing vent.

In the last few years before the balloon as the principal means of flight was eclipsed by the aeroplane, a remarkable young lady came on the scene. Dolly Shepherd was a 16 year old waitress working at Alexandra Palace. She overheard two customers discussing the need to find a replacement for someone to have an apple shot off her head. She promptly volunteered to do the job spent a year as a target with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show.

One day in 1904 Cody took her to see another showman - Auguste Gaudron and his aerial workshop. As a result, Cody lost his target because Dolly became a trainee parachutist. The training was limited – little more than 30 minutes instruction. But Dolly took it seriously and designed her own costume, a navy blue suit with gold trimmings. Her first jump was a full performance watched by a crowd of thousands.

Tests carried out some years later did indeed show that a properly constructed parachute to Cocking’s design (and using Sir George Cayley’s principles) would have worked well. But no one ever felt the need to prove it with a live jump.

A vent in the top of the canopy was soon adopted which achieved a stable descent and drops from balloons became a popular show attraction. Piloted balloons suffered severe loss of control when the weight of the parachute and its occupant was suddenly released so parachutists began to use smaller, unpiloted balloons. They needed no ballast for control and could safely be abandoned by the parachutist at the chosen height. Some were gas-filled, others so-called ‘smoke’ balloons inflated by hot air. To encourage rapid deflation a sandbag was attached to the top of the smoke balloon. At the point of release, this rolled the balloon inverted allowing a rapid escape of hot air from the now upward-facing vent.

In the last few years before the balloon as the principal means of flight was eclipsed by the aeroplane, a remarkable young lady came on the scene. Dolly Shepherd was a 16 year old waitress working at Alexandra Palace. She overheard two customers discussing the need to find a replacement for someone to have an apple shot off her head. She promptly volunteered to do the job spent a year as a target with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show.

One day in 1904 Cody took her to see another showman - Auguste Gaudron and his aerial workshop. As a result, Cody lost his target because Dolly became a trainee parachutist. The training was limited – little more than 30 minutes instruction. But Dolly took it seriously and designed her own costume, a navy blue suit with gold trimmings. Her first jump was a full performance watched by a crowd of thousands.

|

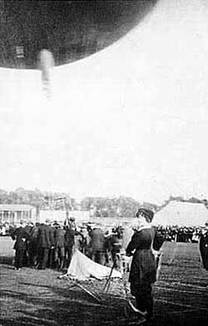

Hanging below a small gas balloon was her parachute and, on a separate cord a trapeze bar. When the balloon was properly inflated it was released and Dolly had to run forward to be underneath it as she was lifted off the ground, sitting prettily on the trapeze bar and waving a silken Union Jack. She checked her height on an aneroid barometer strapped to her wrist. At the right altitude – it varied with the wind speed and thus her distance from the crowd - she had to pull a ripcord to begin the balloon’s deflation and jump off the trapeze so that the parachute would open. |

Needless to say, she was a great success and performed at shows across the country, though not without problems. On one flight the release failed and the balloon went on rising to 15,000 feet. She had to fight the lack of oxygen and severe cold until finally sinking to earth some 3½ hours later.

Her greatest trial came in July 1908 at the Longton Park Fête in Staffordshire. A new jumper, Louie May, was due to make her first descent from Gaudron’s Mammoth balloon, then the largest in Britain. But after they launched Gaudron thought the wind too strong for Louie and refused to let her jump. The disappointed crowd were promised that she would jump the following day. Dolly had been performing at Ashby-de-la-Zouch and joined them that evening. She learned that she and Louie would be making a double jump.

The weather next morning was fine but the Mammoth developed a fault and collapsed – more disappointment. Luckily, Dolly had brought her small balloon, just big enough to lift the two girls. A pony and trap collected it from the station. It took time to rig the two parachutes – one on each side to balance the balloon – and it was 8 pm before everything was ready. Finally the patient crowd saw the balloon lift off.

The planned jumping height was 4000 feet. But there was no release. The balloon drifted out of sight in the evening sky, the frustrated spectators wandered home and the concerned Gaudron set off in pursuit of his girls.

Her greatest trial came in July 1908 at the Longton Park Fête in Staffordshire. A new jumper, Louie May, was due to make her first descent from Gaudron’s Mammoth balloon, then the largest in Britain. But after they launched Gaudron thought the wind too strong for Louie and refused to let her jump. The disappointed crowd were promised that she would jump the following day. Dolly had been performing at Ashby-de-la-Zouch and joined them that evening. She learned that she and Louie would be making a double jump.

The weather next morning was fine but the Mammoth developed a fault and collapsed – more disappointment. Luckily, Dolly had brought her small balloon, just big enough to lift the two girls. A pony and trap collected it from the station. It took time to rig the two parachutes – one on each side to balance the balloon – and it was 8 pm before everything was ready. Finally the patient crowd saw the balloon lift off.

The planned jumping height was 4000 feet. But there was no release. The balloon drifted out of sight in the evening sky, the frustrated spectators wandered home and the concerned Gaudron set off in pursuit of his girls.

At the anticipated moment Louie’s release had failed to work. Dolly used the rope connecting the trapezes to pull them together so that she could try the release - without success. She was concerned that a repeat of her flight to a freezing 15,000’ and a landing in the dark was too much for a first-time jumper. They went into cloud. Emerging at 11,000’, Dolly decided to take action. It was unthinkable to jump herself and abandon Louie so she pulled her across the gap again and, very carefully, unfastened Louie’s harness whilst she clung tightly to the trapeze.

With Louie wrapped around her, Dolly pulled her release and they fell. The parachute did not open properly in the thin air and it fluttered ominously as they plummeted down through the clouds. Then, with a jerk, the chute opened properly and the speed of their fall lessened - although it was still too fast for a normal landing. They were over open country, but coming down perilously close to a road and to land on the hard surface could have been fatal. In the end, they fell onto a field, just six feet from the road and close to a scythe left lying on the ground. They were 14 miles from Longton.

Louie, whose landing was cushioned by Dolly, was unhurt but Dolly lay still, painfully aware that her back was seriously injured. When a doctor eventually arrived he arranged for her to be carried, on a door, to the nearby farmhouse. There she remained for the next eight weeks, generously cared for by the farmer and his family.

The incident generated a storm of publicity with the usual distortion of the facts – Louie apparently ‘leapt several yards’ to reach Dolly - and maximum licence in the fanciful illustrations.

With Louie wrapped around her, Dolly pulled her release and they fell. The parachute did not open properly in the thin air and it fluttered ominously as they plummeted down through the clouds. Then, with a jerk, the chute opened properly and the speed of their fall lessened - although it was still too fast for a normal landing. They were over open country, but coming down perilously close to a road and to land on the hard surface could have been fatal. In the end, they fell onto a field, just six feet from the road and close to a scythe left lying on the ground. They were 14 miles from Longton.

Louie, whose landing was cushioned by Dolly, was unhurt but Dolly lay still, painfully aware that her back was seriously injured. When a doctor eventually arrived he arranged for her to be carried, on a door, to the nearby farmhouse. There she remained for the next eight weeks, generously cared for by the farmer and his family.

The incident generated a storm of publicity with the usual distortion of the facts – Louie apparently ‘leapt several yards’ to reach Dolly - and maximum licence in the fanciful illustrations.

A back specialist was brought from London to examine Dolly and concluded that she would never walk again. He began arrangements for a transfer to a hospital for incurables. But the local doctor had other ideas and used mild electrical therapy to get her legs moving again. Within a few weeks, Dolly was walking and soon after, incredibly, parachuting again.

She flew and jumped successfully for the next four years. One day in 1912, during a solo ascent, she apparently heard a voice telling her to stop or she would be killed. She stopped.

During WWI she served in France as a volunteer ambulance driver and occasionally chauffeured officers. She married one and became Mrs Sedgwick. But that’s not quite all there is to be told. Whilst Dolly was recovering, her mother had secretly jumped in her place. And Dolly’s daughter later became the third generation of female parachutists in this remarkable family.

Dolly’s mid-air rescue is recognised as a first by the Guinness Book of Records. In 1976 she was invited to join the Parachute Regiment’s Red Devils to watch their sky-diving act. She died in 1983, just short of her 97th birthday. But she did leave us her autobiography, ‘When the Chute Went Up’ which is available on Amazon. It’s a cracking read

She flew and jumped successfully for the next four years. One day in 1912, during a solo ascent, she apparently heard a voice telling her to stop or she would be killed. She stopped.

During WWI she served in France as a volunteer ambulance driver and occasionally chauffeured officers. She married one and became Mrs Sedgwick. But that’s not quite all there is to be told. Whilst Dolly was recovering, her mother had secretly jumped in her place. And Dolly’s daughter later became the third generation of female parachutists in this remarkable family.

Dolly’s mid-air rescue is recognised as a first by the Guinness Book of Records. In 1976 she was invited to join the Parachute Regiment’s Red Devils to watch their sky-diving act. She died in 1983, just short of her 97th birthday. But she did leave us her autobiography, ‘When the Chute Went Up’ which is available on Amazon. It’s a cracking read