A very welcome recent arrival in the Shuttleworth hangars is the Percival Mew Gull. It was last here in 2002 and has since been privately owned and based elsewhere. It is entirely fitting that it has returned ‘home’ since it epitomises the spirit of 1930s air racing

and its presence celebrates the life and achievements of Alex Henshaw.

and its presence celebrates the life and achievements of Alex Henshaw.

Alex Henshaw (1912-2007) (Nov 2013)

Alex wanted to be an engineer and, on leaving school, he applied for a Rolls-Royce apprenticeship. But there was a two-year wait. Trying a number of fill-in jobs, including working for his father, he became bored and announced that he was going to buy a decent motor-cycle or perhaps, learn to fly. Recommending the safer option, his father struck a deal with Skegness Flying Club for a training course to ‘A’ Licence for an up-front payment of £35 – well, this was 1932. Having soloed after just six hours Alex was soon a qualified pilot and an enthusiastic owner of a Gypsy Moth. His father too caught the bug and learned to fly at the age of 45.

Alex soon got interested in air racing and bought Comper Swift G-ACGL to compete in the 1933 King’ Cup. The race was in four stages – triangular laps with turning points at various places in East Anglia and the Midlands. Geoffrey de Havilland won in a Leopard Moth but Alex won the Siddeley Trophy for the most promising pilot. (The Swift was sold in 1934 and passed through several owners before being scrapped in 1942. The remains were found in 2008 and it was restored by Skyport Engineering at Hatch. It is now on display at RAF Museum, Cosford).

Having admired its aerobatic displays Alex replaced the Swift with an Arrow Active. He taught himself aerobatics, working towards more advanced manoeuvres such as tail slides and inverted spins. The engine was not capable of prolonged inverted flight and his father watched some spluttering recoveries from odd attitudes. Alex’s next birthday present was a parachute. On a clear December day he set off for Brough to have work done on the engine. On the way he couldn’t resist another attempt to complete a bunt – an inverted loop.

‘I got it up to the vertical inverted position and just when I thought I could I could force it over, the machine hung for a moment in the air, stalled and then slid rapidly back on its tail. I opened the throttle and the engine backfired. The next moment there was an explosion inside the engine cowling and the petrol tank at my feet burst into flame. My first reaction was to uncouple my Sutton harness and draw my feet up away from the heat. By now the flames were streaking up from the bottom of the cockpit as the slipstream acted like the bellows in a blacksmith’s forge. I knew that if the heat melted the flexible fuel lines the tank could explode in my face. . . . With one hefty kick, I went over the side.’

(Only two Arrows were built. Alex’s was destroyed in 1935, the second, pictured above, is still active on the register and lives alongside the Mew Gull in Shuttleworth's hangars)

Henshaw Senior had bought a Leopard Moth and together they toured extensively through Europe, honing their navigational and diplomatic skills. Planning ahead for his flying in 1937, Alex realised that he had no hope of winning races in the Leopard Moth and coveted a Mew Gull he saw at Percival’s Luton factory but found it had been sold. Shortly afterwards he met the man who had bought it, Bill Humble. (He was to become Hawker’s test pilot and also grandfather of Kate, the television presenter). Bill was about to get married and realised that the Mew Gull was not exactly a sociable aeroplane and he could make better use of a Leopard Moth. So they swapped planes.

The Mew Gull was not an easy aeroplane to fly. It certainly had a high cruising speed but with a fixed-pitch prop it needed a long take-off run and it had a high landing speed. Then there was the matter of the very poor, almost non-existent, forward view from the low, cramped cockpit. Alex had mixed fortunes in his races, winning some but having to pull out of the King’s Cup because of engine problems. On one occasion that year bad weather forced him to land and he found himself conveniently near Old Warden. He was greeted by Richard Shuttleworth on a tractor, both covered in mud. ‘I’m glad you’ve dropped in Alex,’ he said ‘You can give me a hand to clear the road I’m making’. After working on the road and chopping down a tree they both flew hops on the Bleriot and Deperdussin.

(Only two Arrows were built. Alex’s was destroyed in 1935, the second, pictured above, is still active on the register and lives alongside the Mew Gull in Shuttleworth's hangars)

Henshaw Senior had bought a Leopard Moth and together they toured extensively through Europe, honing their navigational and diplomatic skills. Planning ahead for his flying in 1937, Alex realised that he had no hope of winning races in the Leopard Moth and coveted a Mew Gull he saw at Percival’s Luton factory but found it had been sold. Shortly afterwards he met the man who had bought it, Bill Humble. (He was to become Hawker’s test pilot and also grandfather of Kate, the television presenter). Bill was about to get married and realised that the Mew Gull was not exactly a sociable aeroplane and he could make better use of a Leopard Moth. So they swapped planes.

The Mew Gull was not an easy aeroplane to fly. It certainly had a high cruising speed but with a fixed-pitch prop it needed a long take-off run and it had a high landing speed. Then there was the matter of the very poor, almost non-existent, forward view from the low, cramped cockpit. Alex had mixed fortunes in his races, winning some but having to pull out of the King’s Cup because of engine problems. On one occasion that year bad weather forced him to land and he found himself conveniently near Old Warden. He was greeted by Richard Shuttleworth on a tractor, both covered in mud. ‘I’m glad you’ve dropped in Alex,’ he said ‘You can give me a hand to clear the road I’m making’. After working on the road and chopping down a tree they both flew hops on the Bleriot and Deperdussin.

Alex had met Jack Cross of Essex Aero who specialised in preparing aircraft for racing and had rebuilt G-ACSS, the DH Comet which won the MacRobertson Trophy in 1934. Cross took the Mew Gull and fitted a new 205 hp engine and spinner enclosing a variable pitch propeller. Thinner wheels and neater spats were fitted and the cockpit and fuselage line lowered. The 1938 King’s Cup proved the effectiveness of the modifications when Alex won at an average speed of 236.25 mph. But his love affair with racing was cooling. He appreciated that success was more dependent on the handicappers than the skill of the pilots or the power of their aeroplanes. Now he looked more to long-distance record breaking and, in particular, the flight to South Africa.

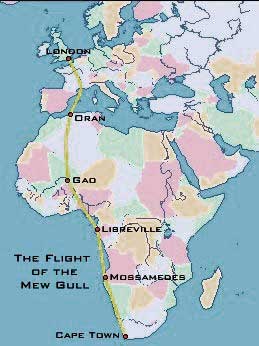

His father bought a Vega Gull and had it fitted with long-range tanks. They set off to survey the route to Cape Town in preparation for a record attempt. The usual route chosen by previous fliers had been to fly to Egypt then ‘join the red dots on the map’ down through East Africa to the Cape. The Henshaws decided to fly out to Morocco and challenge the 1400 mile Sahara desert crossing to West Africa. From Cape Town they came home via East Africa. With all they had learned, Alex agonised over the route to take for his record attempt and finally chose the west coast route. He calculated that it was two hours shorter and avoided the East African hot and high airfields which promised poor take-off performance.

Take-off was planned for 3.30 am on Monday 4th February, 1939. Five minutes late, Alex was lined up on the floodlit Gravesend airfield when a dense fog suddenly rolled in reducing visibility to less than 20 yards. Impatient with all the delays he had suffered Alex uncaged his directional gyro and took off on instruments. After a long, blind run the Mew rose from the fog into a brilliant starlit sky. It wasn’t until he reached Marseilles that he saw enough of the ground to get an accurate fix and to work out that he was achieving 233mph and he was a few minutes ahead of schedule.

Over the Mediterranean he had to descend through cloud before finding his first landing place at Oran, in Algeria.

At Gao, in Mali, he managed to get an hour’s sleep. The take-off was in darkness and the next few hours offered no lights on the ground to aid navigation. Then he flew into the Inter Tropical Front with its towering clouds and bursts of torrential rain. Another long descent through cloud brought him over the Atlantic a few miles from the coast which led to Libreville in Gabon where he re-fuelled.

After a relatively easy leg down the coast he lined up for the landing at Mossamedes in Angola. He usually opened a little window on the right side of the canopy before landing. This was held closed by a simple wire hook and he reached across with his left hand. The Mew hit a bump and the wire hook pierced his finger. He pulled and the hook bit deeper into the flesh. With his right hand on the stick, left locked by the wire and the aeroplane low and undershooting he had to tear his hand away and jam open the throttle. Blood spurted everywhere but the Mew climbed away for a second circuit and uneventful landing.

The final leg to Cape Town was almost an anticlimax, apart from the tiredness which produced occasional hallucinations. He landed at 18.58 on 6th February, an elapsed time of 30 hrs 28 mins, beating the Comet’s record by 6 hours. Now for the return flight.

Take-off was planned for 3.30 am on Monday 4th February, 1939. Five minutes late, Alex was lined up on the floodlit Gravesend airfield when a dense fog suddenly rolled in reducing visibility to less than 20 yards. Impatient with all the delays he had suffered Alex uncaged his directional gyro and took off on instruments. After a long, blind run the Mew rose from the fog into a brilliant starlit sky. It wasn’t until he reached Marseilles that he saw enough of the ground to get an accurate fix and to work out that he was achieving 233mph and he was a few minutes ahead of schedule.

Over the Mediterranean he had to descend through cloud before finding his first landing place at Oran, in Algeria.

At Gao, in Mali, he managed to get an hour’s sleep. The take-off was in darkness and the next few hours offered no lights on the ground to aid navigation. Then he flew into the Inter Tropical Front with its towering clouds and bursts of torrential rain. Another long descent through cloud brought him over the Atlantic a few miles from the coast which led to Libreville in Gabon where he re-fuelled.

After a relatively easy leg down the coast he lined up for the landing at Mossamedes in Angola. He usually opened a little window on the right side of the canopy before landing. This was held closed by a simple wire hook and he reached across with his left hand. The Mew hit a bump and the wire hook pierced his finger. He pulled and the hook bit deeper into the flesh. With his right hand on the stick, left locked by the wire and the aeroplane low and undershooting he had to tear his hand away and jam open the throttle. Blood spurted everywhere but the Mew climbed away for a second circuit and uneventful landing.

The final leg to Cape Town was almost an anticlimax, apart from the tiredness which produced occasional hallucinations. He landed at 18.58 on 6th February, an elapsed time of 30 hrs 28 mins, beating the Comet’s record by 6 hours. Now for the return flight.

The time on the ground, 27 hours, was spent in a blur of dealing with the press, meeting officials, checking the aeroplane and trying, mostly in vain, to take some food and get some sleep. Take-off was at 22.15 on 7th February. For over 6 hours, Alex flew over an unbroken carpet of fog then looked for some sign that he was near Mossamedes. A slight colour change in the fog gradually resolved into the faint glow of fires lit by the Portuguese around their airstrip. The enthusiastic helpers completed the formalities and refuelling quickly and, pausing only to remove all the presents and food which had been put into the cockpit, Alex took off just 45 minutes after landing.

There was little shade from the scorching sun and he began to feel unwell with waves of sickness and either sweating or shivering. He recognised the onset of an attack of malaria. The landing at Libreville restored his concentration although he felt he had treated the white-suited Governor with less respect than he deserved. Airborne again, the sickness returned with bouts of vomiting and stomach cramps. The pain was so great that he allowed the Mew to dive through the cloud whilst he tried to stretch his cramped body. The sight of the approaching ground revived enough interest to take control again to avoid crashing into the thick jungle. Soon he became aware that he was lost. There was no sign of the large tributary of the River Niger that should have been on his track. His bodily pain induced numbness in his brain and he couldn’t decide what to do. To fly straight on led only to the Sahara so he had to turn. Without logic, he turned east. Ten minutes later, the river came into sight and he found the pin point he needed to lead him to Gao.

There was little shade from the scorching sun and he began to feel unwell with waves of sickness and either sweating or shivering. He recognised the onset of an attack of malaria. The landing at Libreville restored his concentration although he felt he had treated the white-suited Governor with less respect than he deserved. Airborne again, the sickness returned with bouts of vomiting and stomach cramps. The pain was so great that he allowed the Mew to dive through the cloud whilst he tried to stretch his cramped body. The sight of the approaching ground revived enough interest to take control again to avoid crashing into the thick jungle. Soon he became aware that he was lost. There was no sign of the large tributary of the River Niger that should have been on his track. His bodily pain induced numbness in his brain and he couldn’t decide what to do. To fly straight on led only to the Sahara so he had to turn. Without logic, he turned east. Ten minutes later, the river came into sight and he found the pin point he needed to lead him to Gao.

The landing was a blur though he remembers being lifted from the cockpit. He was seriously considering abandoning the flight when someone pointed to the flag on the Mew’s tail saying it was a flag to be proud of. That stiffened his resolve. A wash, a ‘celluloid-looking’ pill from a doctor and an hour’s sleep completed his ‘recovery’ and he was airborne again.

The night flight over the featureless Sahara seemed endless. Then little wisps of cloud appeared and the Mew flew through them one by one. The cloud thickened. ‘I sleepily noticed a dark grey mass ahead and was about to plunge into it . . . With a start that literally kicked me into life like a flash of lightning and with a vertically banked turn that nearly blacked me out I swung away from that cloud.’ It was part of the Atlas Mountain range.

The landing at Oran went smoothly though Alex ignored the French met. forecast of thick fog over northern France and southern England. The Mediterranean was bathed in sunshine and the Rhone valley was clear. Alex was just condemning the French met. service when he noticed a colour change in the sky ahead. He took a quick fix before the ground disappeared and he flew into a snowstorm. He had no chance of climbing above the weather and ice began to form on the wings and the screen froze over. Just then ‘I felt something warm gush over my face and suddenly I was covered in blood. The gory mess splashed onto my flannels, maps and knee-pad. My nose and mouth filled and I spat it out as I looked for something to stem the flow. I could find nothing and I weakly rubbed the mess from my face with a bare hand’.

The night flight over the featureless Sahara seemed endless. Then little wisps of cloud appeared and the Mew flew through them one by one. The cloud thickened. ‘I sleepily noticed a dark grey mass ahead and was about to plunge into it . . . With a start that literally kicked me into life like a flash of lightning and with a vertically banked turn that nearly blacked me out I swung away from that cloud.’ It was part of the Atlas Mountain range.

The landing at Oran went smoothly though Alex ignored the French met. forecast of thick fog over northern France and southern England. The Mediterranean was bathed in sunshine and the Rhone valley was clear. Alex was just condemning the French met. service when he noticed a colour change in the sky ahead. He took a quick fix before the ground disappeared and he flew into a snowstorm. He had no chance of climbing above the weather and ice began to form on the wings and the screen froze over. Just then ‘I felt something warm gush over my face and suddenly I was covered in blood. The gory mess splashed onto my flannels, maps and knee-pad. My nose and mouth filled and I spat it out as I looked for something to stem the flow. I could find nothing and I weakly rubbed the mess from my face with a bare hand’.

Then, just as suddenly as he had flown into the snowstorm he flew out into clear air but still with the carpet of French fog below. Until, as if it were cut by a knife, the fog ended and the cold grey Channel appeared below. ‘Never in my whole life had I been so near complete physical and mental exhaustion as the faint shadow of the coastline came in to view’. With a supreme effort to remain conscious he managed to find Gravesend and line up for landing alongside the sea of faces waiting to greet him. He automatically taxied in and collapsed onto sleep as he was lifted from the cockpit.

His records – UK-Cape 6377 miles, 39hrs 23mins, Cape-UK 6377 miles 39hrs 36mins - in a total elapsed time of 4 days 10 hrs 16 mins stood for an astonishing 70 years until May 2009 when South African Chalkie Stobbart ‘reluctantly’ reduced the time to 3 days, 15 hrs 17 mins.

On the outbreak of WWII, Alex volunteered to join the RAF. Whilst waiting for his application to be processed he was invited to join Vickers as a test pilot. But he soon lost interest flying Wellingtons and Walruses and was about to leave when Jeffrey Quill invited him to be Chief Test Pilot at the factory in Castle Bromwich. Over 11,600 Spitfires (more that 50% of the total production) were built at Castle Bromwich and Alex is believed to have tested more than 10% of them. He also flew – and barrel-rolled – some of the 350 Lancasters made by the factory.

During this time he lived at Hampton-in-Arden and often commuted to work in a Hawker Tomtit, landing in a field at the bottom of his garden, sometimes with the landing aid of a torch wielded by his wife. The Tomtit acquired a Spitfire’s windscreen and headrest. Today, that very machine lives in Shuttleworth’s hangar alongside the Mew Gull.

The Gull itself spent the war hidden in France. It suffered several rebuilds, the last one to its original configuration. Happily it was re-united with Alex Henshaw in 1989, appropriately enough, at Old Warden.

The Gull itself spent the war hidden in France. It suffered several rebuilds, the last one to its original configuration. Happily it was re-united with Alex Henshaw in 1989, appropriately enough, at Old Warden.