The Croydon – its Timor Terminus (June 2019)

Helmut Steiger was a Swiss aircraft engineer who completed his training at Imperial College in London. There were job opportunities at several of the small companies building aeroplanes in the early 1920s. Helmuth went to work for one of the largest, William Beardmore and Company. Beardmore had an impressive record. They began in Victoria’s reign building ships on the Clyde, expanded into railway locomotives, cars, taxis, a wide variety of engines and, during WWI, Sopwith Pups. They developed the Pup and produced their own line of shipborne fighters for the Royal Navy. Also they built a number of airships, culminating in the R34, which in 1919 was the first aircraft to make an east-west crossing of the Atlantic – and to make a return flight.

In 1924, Beardmore acquired a licence to use the Rohrbach method of stressed skin production for aircraft. They had built a flying boat then, just as Helmuth joined the company, began the construction of the Rohrbach Ro VI, a tri-motor transport for the RAF with a huge wing spanning 157 ft. Appropriately, it was to be known as the Beardmore Inflexible.

Young Steiger was bemused by the heavy and complex construction of the Inflexible’s main spar. He sketched out his own ideas for a duralumin spar, a braced Warren girder which would be both strong and light weight.

Beardmore, of course, were not interested. The large components of the Inflexible were built in Glasgow and then transported, by sea, to the RAF’s experimental station at Martlesham Heath in Suffolk. There they were assembled into an aeroplane. The Inflexible flew but, despite its three RR Condor 650 hp engines it was seriously underpowered and overweight and never used in service.

Beardmore, of course, were not interested. The large components of the Inflexible were built in Glasgow and then transported, by sea, to the RAF’s experimental station at Martlesham Heath in Suffolk. There they were assembled into an aeroplane. The Inflexible flew but, despite its three RR Condor 650 hp engines it was seriously underpowered and overweight and never used in service.

Steiger, meanwhile, had moved on to team up with a fellow Imperial College student, Francis Crocombe. They formed the Monospar Wing Company and managed to get an Air Ministry contract to build a flying scale prototype, named the ST-1, to prove the wing.

This was displayed at the Aero Exhibition at Olympia in 1929 - ironically, the same year in which Beardmore closed down their Aviation Division. The interest of the Air Ministry was sufficiently aroused for them to have Monospar build a larger wing to be fitted on a Fokker F.VII tri-motor.

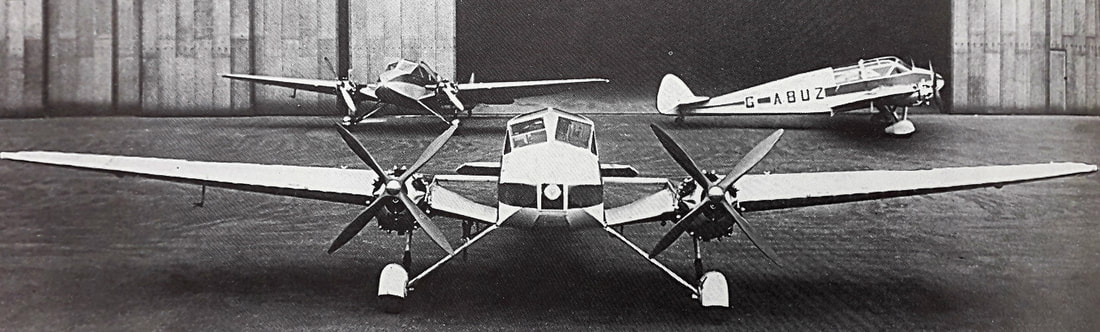

Steiger and Crocombe aimed at a different market and designed a small twin-engined tourer for general aviation use. They set up the General Aircraft Company and, in 1931, the GAL ST-4 Monospar emerged. Powered by twin Pobjoy R 85 hp radial engines it carried a pilot and three passengers, cruising at 115 mph.

This was displayed at the Aero Exhibition at Olympia in 1929 - ironically, the same year in which Beardmore closed down their Aviation Division. The interest of the Air Ministry was sufficiently aroused for them to have Monospar build a larger wing to be fitted on a Fokker F.VII tri-motor.

Steiger and Crocombe aimed at a different market and designed a small twin-engined tourer for general aviation use. They set up the General Aircraft Company and, in 1931, the GAL ST-4 Monospar emerged. Powered by twin Pobjoy R 85 hp radial engines it carried a pilot and three passengers, cruising at 115 mph.

It was well received and 30 were built appearing in several parts of the world, as far away as Australia. Variants followed. The ST-6 had a fifth seat and a manually retracting undercarriage. The ST-10, with 90 hp Pobjoy Niagara engines had a maximum speed of 144 mph. Flt Lt Schofield took Steiger as his navigator when they flew it to win the 1934 King’s Cup Air Race. Here Helmut stands in the opened cockpit to enjoy a celebratory cigarette.

Francis Crocombe

Francis Crocombe

The ST-6 was fitted with 130 hp DH Gipsy Major engines which greatly improved its performance. Steiger’s patented spar was used by Saunders-Roe for their new amphibian, the Cloud. A specially built wing was ordered by the Italian Air Ministry who tested it on a Caproni transport.

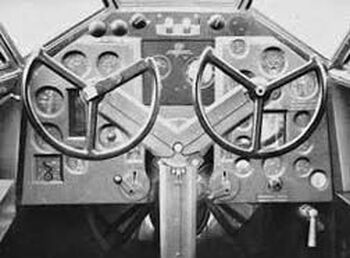

In 1934, the company was restructured with an injection of capital and Crocombe and Steiger’s thoughts turned to higher things. They decided that Francis Crocombe would take the lead in the design of an airliner. An airliner which would carry 10 passengers in superior airline comfort in a sound proofed cabin, with a toilet and separate baggage compartment. An airliner with all the latest developments in aircraft design – hydraulically retracting undercarriage, trailing edge flaps, variable pitch propellers, de-icing system and dual pilot control with full instrumentation. Its design number would be ST-18 and it would be named the Croydon.

In 1934, the company was restructured with an injection of capital and Crocombe and Steiger’s thoughts turned to higher things. They decided that Francis Crocombe would take the lead in the design of an airliner. An airliner which would carry 10 passengers in superior airline comfort in a sound proofed cabin, with a toilet and separate baggage compartment. An airliner with all the latest developments in aircraft design – hydraulically retracting undercarriage, trailing edge flaps, variable pitch propellers, de-icing system and dual pilot control with full instrumentation. Its design number would be ST-18 and it would be named the Croydon.

There was a problem, of course. There was no suitable British engine available. The Bristol Aquila would be fine, but it was still in development. So, for the prototype, they would fit two American Pratt and Whitney Wasp Junior engines of 400 hp which should give a cruising speed of almost 200 mph. The prototype Croydon would make a sales tour with the Wasps and the Aquila would be ready when the first Croydons came off the production line.

Crocombe took advantage of the clever single spar design. The wings were slightly swept back and the spar crossed the cabin well forward in the fuselage, in fact, at the bulkhead behind the pilot’s cockpit. So the passenger cabin floor was completely flat and unobstructed. On 16th November, 1935, the Croydon took off from Hanworth on its first flight, piloted by Flt Lt Schofield.

Crocombe took advantage of the clever single spar design. The wings were slightly swept back and the spar crossed the cabin well forward in the fuselage, in fact, at the bulkhead behind the pilot’s cockpit. So the passenger cabin floor was completely flat and unobstructed. On 16th November, 1935, the Croydon took off from Hanworth on its first flight, piloted by Flt Lt Schofield.

The flight testing went well though there was no sign of any order for the airliner. Then, in July 1936, the press were invited to a luncheon at Hanworth. It was announced that Lord Sempill was to fly the Croydon on the Empire air routes - in practice, that meant a flight to Australia. Lord Sempill had served in the RFC, RNAS and the RAF and had subsequently set some point to point air records. He was President of the Royal Aeronautical Society. The Croydon itself had been bought by Major C R Anson (as a way of investing in the company) and he would lend it to Lord Sempill for the flight. Major Anson also agreed that his own pilot, Tim Harold Wood, would fly the Croydon on the 25,000 mile journey to Melbourne and back. Lord Sempill stressed that there would be no attempt to set any record. The flight would be done under normal service conditions i.e. full load and normal cruising speeds. The only modifications were the fitting of tanks holding an extra 40 gallons of fuel and some additional wireless aerials. An engineer, L. Davies and a wireless operator, C. P. Gilroy were hired.

On 30th July the Croydon took off from Hanworth and made good progress across Europe into Iran – or Persia as it then was. When landing at Bushire, the tailwheel sustained some damage which was not detected. After another stop at Jask, they headed for Karachi. Bad weather forced them to return to Jask where the tailwheel collapsed on landing. Davies made a temporary repair and they flew on to Karachi where there were better engineering facilities.

It was September before the repairs were finished and tested and the Croydon could continue its flight. Overcoming monsoon rains and electrical storms they reached Australia in time to take part in the Victoria Aero Club Pageant in which they were pleased to win the Herald Cup.

During the preparations for the return flight any talk of trying for a record was dismissed, although the Croydon’s cruising speed of 170 mph made a record comfortably achievable. They left Melbourne on 6th October and reached Darwin recording an average speed of 188.4 mph for the 2,435 mile leg, including two refuelling stops.

During the preparations for the return flight any talk of trying for a record was dismissed, although the Croydon’s cruising speed of 170 mph made a record comfortably achievable. They left Melbourne on 6th October and reached Darwin recording an average speed of 188.4 mph for the 2,435 mile leg, including two refuelling stops.

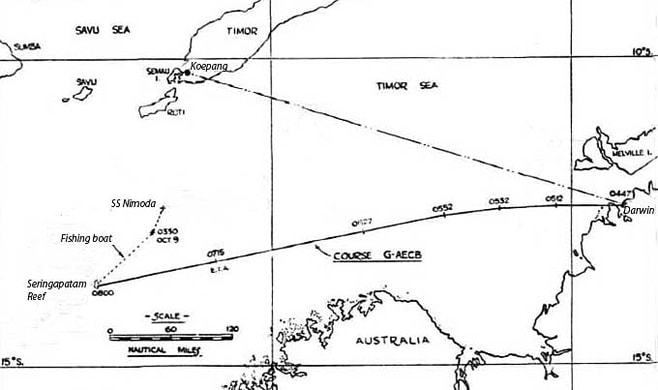

The distance to Koepang in Timor was 518 miles. It had taken them 3¼ hours on the previous crossing. The true bearing was 287° and Harold Wood set a course on his compass of 282°, allowing 4°E magnetic variation and 1°drift. Twenty five minutes after take-off Darwin gave them a bearing of 288° which indicated that they were just 1° north of track. Wood changed his course to 280° and flew on for 20 minutes, expecting to intercept his correct track.

The next bearing was a surprise. 288.5° meant that they were even further north of track than before. Wood suspected the compass and turned 5° south, now heading 275°. Twenty minutes later Darwin’s bearing was 289°, still apparently north of track. Wood asked Gilroy to radio for confirmation. The reply came that the bearing was ‘first class’, meaning that it was accurate to within plus or minus one degree. Now with no faith in his compass Wood turned to 270° and flew on for another 30 minutes.

Darwin’s next bearing was 288°. The estimated time of arrival at Koepang was 0715 and it was now 0622. There was no point in making further minor alterations of course and soon they would be out of radio contact with Darwin. They flew on over an empty sea, reducing height to 3000 ft to be clear of cloud. The ETA passed and it wasn’t until 0800 that they spotted a reef. Land had to be close. They followed the reef and off its northern end was a fishing boat. They found an empty can, wrote on it ‘Which way Koepang?’ and threw it out. The fishermen didn’t notice.

At 0900 they were still circling the reef and the fuel remaining was good for about 180 miles, but which way? They decided to try landing on the reef. They would find out where they were and, just possibly, take off again and fly to land. If that didn’t happen, the fishing boat would rescue them.

Crocombe sat alongside the pilot, Davies and Gilroy went right to the back of the cabin. Wood lowered the wheels and approached the reef. The wheels touched and the surface seemed firm so Wood went round again and this time approached with flaps down. He made a delicate three point landing and the Croydon rolled to a stop just short of some boulders. Maybe the fishing boat had some fuel they could use.

The next bearing was a surprise. 288.5° meant that they were even further north of track than before. Wood suspected the compass and turned 5° south, now heading 275°. Twenty minutes later Darwin’s bearing was 289°, still apparently north of track. Wood asked Gilroy to radio for confirmation. The reply came that the bearing was ‘first class’, meaning that it was accurate to within plus or minus one degree. Now with no faith in his compass Wood turned to 270° and flew on for another 30 minutes.

Darwin’s next bearing was 288°. The estimated time of arrival at Koepang was 0715 and it was now 0622. There was no point in making further minor alterations of course and soon they would be out of radio contact with Darwin. They flew on over an empty sea, reducing height to 3000 ft to be clear of cloud. The ETA passed and it wasn’t until 0800 that they spotted a reef. Land had to be close. They followed the reef and off its northern end was a fishing boat. They found an empty can, wrote on it ‘Which way Koepang?’ and threw it out. The fishermen didn’t notice.

At 0900 they were still circling the reef and the fuel remaining was good for about 180 miles, but which way? They decided to try landing on the reef. They would find out where they were and, just possibly, take off again and fly to land. If that didn’t happen, the fishing boat would rescue them.

Crocombe sat alongside the pilot, Davies and Gilroy went right to the back of the cabin. Wood lowered the wheels and approached the reef. The wheels touched and the surface seemed firm so Wood went round again and this time approached with flaps down. He made a delicate three point landing and the Croydon rolled to a stop just short of some boulders. Maybe the fishing boat had some fuel they could use.

Carefully, Wood taxied the Croydon away from the boulders to a higher part of the reef. Suddenly, the tailwheel dropped into a hole and broke. The tail went down, the tailplane grounded and the elevator controls went slack. When they climbed out and walked on the reef it was no consolation to see how rough it was and how lucky they had been to land successfully. They realised that a take-off would have been impossible. They rigged an aerial, even starting an engine to charge the battery and boost the power of their transmitter but, although they could hear Koepang they could not make contact.

Off-loading their collapsible rubber boat they bid a sad farewell to the marooned Monospar and paddled out to the fishing boat. Finally they learned where they were. They had landed on the Seringapatam Reef, miles off course. They had found it during a period of neap tides and at low water. A week later it would have been under 14 ft of sea.

Off-loading their collapsible rubber boat they bid a sad farewell to the marooned Monospar and paddled out to the fishing boat. Finally they learned where they were. They had landed on the Seringapatam Reef, miles off course. They had found it during a period of neap tides and at low water. A week later it would have been under 14 ft of sea.

The fishing boat was taking the castaways to Koepang when the SS Nimoda hove into sight. They happily transferred to this, only to learn that it was sailing to Durban in South Africa. This gave them more time to mull over their adventure. Though the mishap was clearly the fault of the Darwin’s faulty direction finding the Australian authorities countered by blaming Wood for flying with a defective compass.

It was the end of the Croydon. General Aircraft decided not to build another. They concentrated on the latest model of their most successful Monospar, the ST-25 – given that out of sequence number in celebration of King George V’s 25 years on the throne and sometimes called the Jubilee. More than 60 were built and widely used by discerning aviators, including Jim and Amy Mollison. It was the last of Francis Crocombe and Helmut Steiger’s designs to carry the ST name. Future General Aircraft models were GAL, that is, of course, until the company merged with Blackburn when the GAL Universal Freighter became the Blackburn Beverley.

That is another story entirely.

It was the end of the Croydon. General Aircraft decided not to build another. They concentrated on the latest model of their most successful Monospar, the ST-25 – given that out of sequence number in celebration of King George V’s 25 years on the throne and sometimes called the Jubilee. More than 60 were built and widely used by discerning aviators, including Jim and Amy Mollison. It was the last of Francis Crocombe and Helmut Steiger’s designs to carry the ST name. Future General Aircraft models were GAL, that is, of course, until the company merged with Blackburn when the GAL Universal Freighter became the Blackburn Beverley.

That is another story entirely.